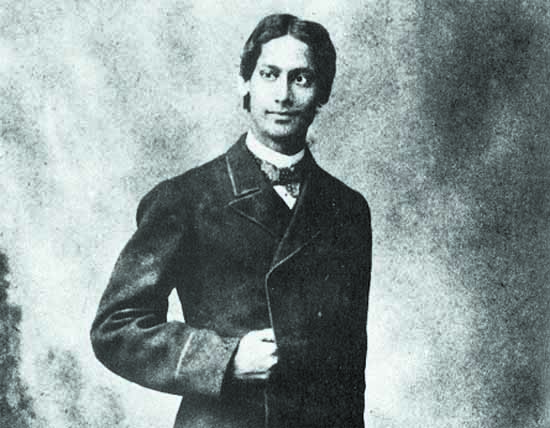

Today, the Bengali calendar marks the 81st death anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore, the stalwart poet of Bengal. On this occasion, The Antonym presents a series of translations of autobiographical notes and letters written during his teenage years as he ventured into foreign lands, stepping outside his home for the first time. These writings reveal a different side of him, not the poet superior or the meditative philosopher but one that is endearingly humane, full of a sparkling sense of humor yet astonishingly perceptive. Contrary to the hefty themes in his lifelong literary journey of poems, songs, stories, novels, and essays, these narrations of the wide-eyed gaze of a young boy who has left home and is struggling to understand the myriad ways of the world come out as far more candid and creates an instant connection with the modern reader.

The first of the series, translated by Manjira Dasgupta, is an attempt at translating an episode from Bilaat (In the Western Land)—part of his autobiographical work Jeevan Smriti— narrating an episode that stands out in its satire and unalloyed humor.

In The Western World

Translated from the Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta

All the while during my stay in England, I got tangled up in a burlesque act. I had got acquainted with the widow of a high official who had been posted in India, and the lady used to affectionately call me ‘Ruby’. An Indian friend of hers had composed an elegy in English upon the death of her husband. The less said about the literary and poetic merits of the composition, the better.

To my utter misfortune, the elegy came with the instruction that it should be sung in Bihag raga. One day, the lady cajoled me into singing her the song in Bihag raga and I obliged, out of courtesy. Luckily, none except me was present there who could appreciate the utter ridiculousness of that strange verse put to tune in Bihag raga. The lady was happy, and I was relieved that this was the end of the episode. Alas, I had been too optimistic.

I used to meet the widow quite often at parties. After dinner, when all the guests—gentlemen and ladies—would assemble in the drawing room, she would request me to sing that song in Bihag raga. The others, expecting that they would be getting to hear an exotic example of Indian Classical music, would join the lady’s earnest enjoining. Thereupon, the inevitable printed page would emerge out of the lady’s pocket—and my ears would start reddening. I would start my song bashfully, with a bowed head—only too aware that it was me alone, and no one else, for whom the consequences of this shok gatha (requiem) were to be utterly tragic. The song would be greeted by suppressed laughter, and an excessively polite, “Thank you very much. How interesting,” upon which, I would start sweating even in the cold winter. Who could have imagined that the demise of the honorable gentleman would prove to be such a misfortune for me.

After this, there was a long gap before I met her again. She would often request me to visit her house on the outskirts of London. I used to decline with all my might, dreading the requiem. At last, one day her telegram came when my return to Kolkata was imminent. So, I thought I should keep the lady’s request before my departure from England.

On that fateful evening, I went to the station straight from College. The day was wintry and chilly. I knew that my destination was the last station on this line—and so, I sat, without worry, reading my book—oblivious of when I would have to get down.

One by one, passengers from London left the train at their respective destinations. By then, it had become pitch dark—without a light or a soul in sight. The train kept moving towards my destination station, but then started moving in the reverse. I surmised this to be some whimsical ways of trains and resumed my reading without paying much attention.

But it became difficult for me to stay nonchalant when I discovered that the train had come to a halt at the very station we had left behind. In a panic, I asked people when my station would come, only to be told that it was the station that we had just left. By now, in a state of panic, I asked where the train was going. They replied, “London”. Flustered beyond measure, I got off the train, and learned further that there was no other train that night, nor was there an inn within five miles.

I had eaten breakfast at ten in the morning, and since then, I had not had even a drop of water. But when you have no other path open to you other than the ascetic one, renunciation becomes your last resort. And so, there I sat, beneath the lamppost, reading the newly released Data of Ethics by Herbert Spencer. I consoled myself by assuring myself that I had been accorded a rare and splendid opportunity to read the book with undivided concentration.

Sometime later, the porter came and announced that a special train would be arriving within half an hour. My elation at the good tidings made it nearly impossible for me to concentrate on Data of Ethics any longer.

When I reached my hostess’ place at half past nine instead of the scheduled seven o’clock, she said, “Why, what is the matter, Ruby?” I narrated my amazing travelogue not too proudly.

The guests had just finished their dinner. I had a faint hope that as my crime was not willingly committed, I would be spared harsh punishment—especially as the arbiter was a lady. But, that high official’s widow told me, “Come, Ruby, have a cup of tea”.

I never take tea, but hoping that a cuppa could calm the stomach pangs, I drank that strong bitter tea with a few biscuits. Coming to the living room, I discovered a number of aged ladies—and a beautiful American lady who was betrothed to my hostess’s nephew.

Our hostess said, “Come! Let us dance.” Now, as for myself, I had no desire whatsoever to dance, and indeed, neither was in a state to, but then, those that are the meekest of men perform miracles in this world. Therefore, even though this dance gathering had been arranged principally for the engaged young couple, I ended up dancing with a number of aged ladies without having eaten anything since the morning apart from a few biscuits.

But more surprises were in store for me when my hostess asked me, “Ruby, Where are you planning to spend the night?” As I stared at her, bewildered, she kindly informed me “All the inns here close at two in the night, so I think you should not delay.” It would be unfair to blame her for total discourtesy—a servant did accompany me to the inn with a lantern in hand.

It seemed like a blessing in disguise, after all—probably they would provide some sort of meal at the inn—be it vegetarian or non-vegetarian, fresh or stale. After they said, “Sorry, you can have as much to drink as you like, but no food,” I consoled myself by thinking that the goddess of sleep would provide me some respite—if not with nourishment, then with blessed oblivion. Alas, even she spurned me that fateful night… The sandstone-floored room was relentlessly chilly, and all it consisted of were an old cot and a decrepit washstand.

Next morning, the Anglo-Indian lady called me over for breakfast. It was what the British call a ‘cold meal’. This means that the previous night’s feast was served in the morning to be eaten cold. Had I been offered even a morsel of this meal last evening, hot or even lukewarm, perhaps no one would have been harmed, nor would my dance performance have resembled the pathetic spasms of a fish pulled out of water.

After the repast, my hostess said, “The person for whom you have to sing the requiem is sick and bedridden. You have to stand outside her room and sing.” I was made to stand on the staircase. The lady pointed at the closed door and said, “She is in that room”. I stood facing the unknown and unseen, and sang the dirge in Bihag raga. I was not able to learn from hearsay or from newspapers about the effect that my song had on the patient.

After my return to London, I had to atone for my exaggerated meekness by being bedridden for two or three days. Dr. Scott’s[1] daughters said, “For God’s sake, Robi, please do not take this horrendous invitation as an example of our country’s hospitality. This is entirely the credit of the Indian climate of yours!”

[1] The loving family that hosted Rabindranath during his first visit to London.

Translator’s Note

Perhaps, a trait that is common to most people whom we revere as great personalities, is the rare gift of being able to laugh, not only at themselves as persons, but even at some of the (minor) misfortunes that might befall them at different points in their celebrated lives.

On turning seventeen, the young Rabindranath Tagore was sent to England by his family to become an Indian Civil Servant, or in another view, to become a barrister. Whichever may have been the purpose of this first visit to Europe, it was an undertaking in which young Rabi failed supremely.

As the poet himself puts in his lyrical prose,

“বিলেতে গেলেম, বারিস্টর হই নি। জীবনের গোড়াকার কাঠামোটাকে নাড়া দেবার মতো ধাক্কা পাই নি, নিজের মধ্যে নিয়েছি পূব–পশ্চিমের হাত মেলানো—আমার নামটার মানে পেয়েছি প্রাণের মধ্যে।” (I went to England but I never became a barrister. I did not feel the drive that could shake the essential framework of my life, I have simply absorbed the confluence of the east with the west within me– I have discovered the meaning of my name within my soul.)

In the bargain, Bengal was blessed with some of the finest prose, usually in the form of letters and journals—where his everyday experiences in England (and later, other countries) are chronicled in unparalleled style. The autobiographical Jeevan Smriti, too, bears some accounts of this phase, for instance, the pieces “বিলাত”, or “বিলাতি সংগীত”, to name a few.

These earlier accounts and the poet’s first impressions of the West are an astonishing blend of acute observation, his sense of wonder, and quite frequently, eloquent commentaries on some absurd situation or the other.

To read the next episodes of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

Wonderful read. Beautifully translated, retains the original flow and spontaneity. Would love to read some more

This is top class translation of a well known ( to Bengali readers) part of a masterpiece. The style is so smooth and limpid that the sentences of the original came back to me as I read. A beautiful piece that makes us hungry for more by Manjira. I knew she is an enthusiastic reader of both English and Bengali literature( in addition to being a competent economist), but this side of her talent is a delightful surprise. Many thanks , Manjira. Please continue to give us more of Tagore and other greats of bangla sahitya.

Excellent translation.

We expect more and more. I also request you to start writing seriously henceforth, not only in English but also in Bengali.

Tagore is a timeless jewel. I enjoyed this deeply. Thank you.

আপনার লেখাটা পড়ার পর ‘জীবন-স্মৃতি’ থেকে ‘বিলাত’ পরিচ্ছেদ-টা আরও একবার পড়লাম। মূল রচনা আর অনুবাদ দুটো-ই একই সঙ্গে পড়ার পর মনে হলো, ভাষার প্রয়োগ আর ভাবের প্রকাশ দুটোই ভীষণ রকমের সুন্দর হয়েছে।

ছোটবেলায় ইংরেজিতে কাজ চালাবার মতো সাবলীল হওয়ার আগে – শার্লক হোমস, আগাথা ক্রিস্টি বা শেক্সপিয়ার এর কিছু বাংলায় অনূদিত গল্প পড়েছিলাম। পরবর্তীকালে, মূল রচনা গুলো পড়ার পর বুঝতে পেরেছিলাম অনুবাদকেরা আসল গল্পের প্রতি কি ভয়ঙ্কর অবিচারটাই না করেছিলেন। প্রতিটি শব্দের আক্ষরিক অনুবাদের ফলে গল্পের মূল ভাবটাই হারিয়ে গেছিলো। পাঠক হিসাবে কোনো গল্প বা লেখা পড়ার সময় মনের মধ্যে একটি কল্পিত চিত্র ভেসে ওঠে, একজন অনুবাদকের মূল প্রচেষ্টাই হলো সেই চিত্রটাকে একই রকম ভাবে তুলে ধরা। এবং এটা আপনি অসাধারন ভাবে করেছেন।

শুধুমাত্র একটা বা দুটো জায়গায় আমার মনে হয়েছে হয়তো ভাব প্রকাশটা আর একটি অন্যরকম হতে পারতো (যদিও এটা পুরোপুরো আমার নিজস্ব দৃষ্টিভঙ্গি, অন্য কেউ ভিন্নমত হতেই পারেন) যেমন – “I had a faint hope that as my crime was not willingly committed, I would be spared harsh punishment— especially as the arbiter was a lady”, এখানে মূল রচনায় রবীন্দ্রনাথ লিখেছেন “আমার মনে ধারণা ছিল যে, আমার অপরাধ যখন স্বেচ্ছাকৃত নহে তখন গুরুতর দণ্ডভোগ করিতে হইবে না—বিশেষত রমণী যখন বিধানকর্ত্রী।” এক্ষেত্রে তার ধারণা “ক্ষীণ” বা “দৃঢ়” তা স্পষ্ট ভাবে বোঝা যায় না। আমার যেমন মনে হয়েছে এখানে দৃঢ়তার ভাবই প্রকাশ হয়েছে।

আবার, আগের এক অনুচ্ছেদে রবীন্দ্রনাথ লিখেছেন “গত্যন্তর যখন নাই তখন এই জাতীয় বই মনোযোগ দিয়া পড়িবার এমন পরিপূর্ণ অবকাশ আর জুটিবে না এই বলিয়া মনকে প্রবোধ দিলাম।” এই “এই জাতীয় বই” কথাটার মধ্যে দিয়ে একটা শ্লেষাত্মক ভাব (মতান্তরে প্রশংসা-সূচকও হতে পারে) ফুটে ওঠে। এই ভাবটা এই অনুবাদের মধ্যে অবর্তমান।

কিন্তু, সবার শেষে একটাই কথা ভীষণ সুন্দর হয়েছে, আরও অনেক এই ধরণের লেখা পাওয়ার অপেক্ষায় থাকলাম।

Beautiful work , clearly reflects the hard work and professional touch . Please gift us more like this Regards

Beautiful. It is a pleasure to read and also reflects the command over the subject by the writer. Bravo. Eagerly waiting for more.

“Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation” – Dr. Manjira Dasgupta shouldered a tremendous responsibility and courage of taking the words of Kabi Guru Rabindranath Tagore to the english speaking world. Valuable thoughts and writings of Tagore(Travel in the Western world) and the treasures of history that he captured in his writing during his travel is now accessible to a much wider set of readers and audience and Manjira has done justice to the weighty words of Tagore. Preserving an important part of our culture and passing on our heritage as bengali’s is something that Manjira’s work has successfully accomplished. Kudos to you Manjira and we are eagerly waiting for a lot more works in this field from you!

Enjoyed reading & the simple clear style.

Delightfully translated Manjira. I never knew this dimension of your lateral talent before. Very eloquent style of your paraphrasing indeed. Read the original masterpiece decades ago. Not even remembering everything that very meticulously though, was trying to reminisce some of the original anecdotes of the greatest through your decoded lines.

Do keep up the profound practice and offer us few more excellence from your kitty!