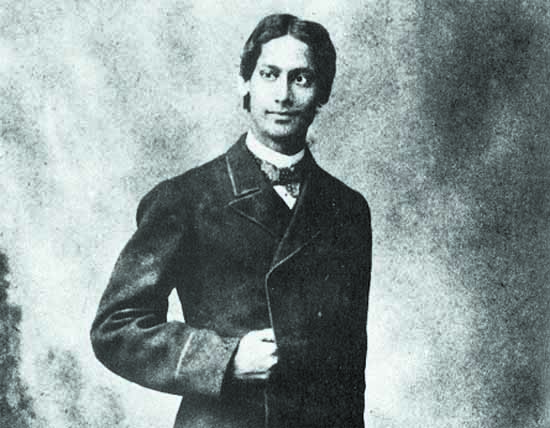

This is the second installment in our series on a selection of the journals and correspondences that Rabindranath Tagore had penned during his visits abroad, particularly, in Europe. Below, we have the seventeen-year-old poet’s eloquent description of his first voyage to Europe, undertaken in 1878. Some of the descriptions were reproduced partly in the autobiographical Jeevan Smriti, as well as in the correspondence Europe Probashir Potro (Letters from Europe). The second voyage to Europe, undertaken twelve years after this (1890), is similarly chronicled in Europe Jatrir Diary.

Our first piece in this series was a seriocomic episode from Tagore’s maiden stay in England. As Majid Mahmood (2020) notes, the details of this first Europe journey are rather scarce, except for the poet’s own version. Hence, in chronicling this part, we have no other recourse open other than to refer to Tagore’s letters Europe Probasir Potro, addressed to Jyotirindranath Thakur. According to Tagore’s biographer Prashanta Kumar Pal, the letters were started on the ship and were concluded after reaching Brighton (Mahmood 2020).

Finally, a unique style of the narrator here is the effortless back and forth between the present tense and the past—which we have tried to retain. The following is the 1st letter from Europe Probashir Potro.

Letters From Europe— 1st Letter

Translated from the Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta

We boarded the vessel Poona on the 20th of September. The ship sailed at five o’clock with us standing on the deck. Gradually, in front of our eyes, the last shoreline of India faded away. Unable to stand the general chatter around me, I went to my cabin and lay down. I am not ashamed to admit that my mind was too depressed and despondent. But let us say good riddance to such gloomy thoughts, I am neither in the mood nor have the time to dwell on the melancholy, and even if I were to write such stuff, you would have neither tears to spare nor the patience.

A hundred salutes to the sea. Only I know how I spent the 20th to 26th. You may have heard of ‘seasickness’—but probably have not even the faintest idea of its reality. Even the sternest of souls would be moved to tears if I were to describe my ordeals. My dear fellow, I could not bring myself to get up from the bed for six long days and had stayed confined in the shallow and dark cabin with all the windows closed lest the seawater got inside. I barely survived unseen by the sun and untouched by air for those six days.

On the first evening, one of our co-passengers forced me out of the bed and took me to the dining table. Standing up, I felt everything inside my head at battle with each other—I could neither see a thing nor could I move my legs—my whole body kept trembling. I collapsed on a bench after barely walking two steps. My companion caught hold of me and led me to the deck, where I leaned against the rail. The night was dark—the sky overcast. The wind was blowing against us. In that gargantuan darkness, amidst the solitary boundless ocean, our lone ship sailed emitting fire on both sides. Wherever one gazed, there was only darkness with the ocean swelling—a magnificent sight indeed.

I could not stay long on the deck—my head was reeling. Again, they helped me to my cabin, and I collapsed on the bed to not raise my head even for a minute for the next six whole days. For some unknown reason, the steward of the ship had taken mercy and had a sympathetic attitude toward me. Every so often, he would get me food and would not leave until I ate it. He commented that I would go “weak as a rat” if I starved. He also pledged to do anything I might ask for. I was generous with my compliments to him and gave him something more substantial than compliments when I finally left the ship.

The sea had turned calmer as we approached Aden after six days. My steward repeatedly asked me to move about a bit. As soon as I got up, I realized that I had indeed become as weak as a rat. My head felt as if it belonged to someone else, totally out of sync with my own neck, my body hung loose like a stolen piece of cloth, not fitting its owner. I stepped out and slumped immediately on a recliner on the deck. The fresh air felt good.

On reaching Aden, I started writing home. But it seemed as if absolute anarchy had invaded my brain. I simply could not contemplate how and what to write. My thoughts, frail like spider webs, snapped as soon as I attempted to touch them and it was impossible to arrange ideas coherently. It is in this state that I am writing to you. Please do not be disappointed.

When I began moving around, my glance fell on my co-passengers on the ship, and theirs on me. By nature, I stand in dread of the ‘ladies’. Pundit Chanakya had warned mankind of the multitudinous perils that may befall one under the influence of the fair sex that I could not help but stand in dread of the ‘ladies’.

To start with, there were potential catastrophes (that could be wrought) on one’s psyche. Apart from that, I was always worried that I might utter something inappropriate that would horrify or scandalize our overly sensitive fair ladies. I might, for example, lose myself and get flustered in the maze of gowns, or, on being called upon to carve the meat during dinner, I might end up carving my own finger instead—such imagined calamities forced me to maintain a great distance from them. There was no dearth of ladies on our ship. However, the gentlemen would constantly lament that none among them were young or beautiful.

I got acquainted with many of the male co-passengers. We became quite close to Shri B—a man of incessant words, plentiful laughter, and unrestricted eating. He knew everybody and had an easy camaraderie with all. He neither spoke nor acted like his age or status. I was drawn to him for his smile was never measured, nor were his opinions guarded. He spoke frankly and did not try to appease anyone. He was so childlike in his ways, an endearing combination of the wisdom of the aged and the straightforwardness of the young. He called me the ‘Avatar’, Mr. Gregory was ‘GoRgoRi’ (An Indian version of the Hookah) to him. Another co-passenger was attributed as the Rohu Fish, as he had a very short neck so that his head and body seemed welded together. However, as to what made me fall into the category of ‘Avatars’, I could find no reason.

Mr. T, aboard our ship, was a novel creature. A philosopher to the core, he never spoke in colloquial language. He did not converse, he gave speeches. One evening, a few of us were amusing ourselves on the deck, when, unfortunately, B remarked, “How beautiful the stars are!” Upon which, our philosopher friend started a humongous speech on the relationship between the stars and human life—and we stared at him like idiots.

Our ship also contained a John Bull incarnate. His stature was like a palm tree with a broom-stick mustache and hedgehog hairs. His face resembled an enormous cauldron and his eyes seemed dead as fish. I used to feel quite sick just looking at him. Every morning one could hear him stomping around and abusing all the servants on the ship in English, French, Hindustani, and the like. I had never seen him smile, nor talk to anyone—he used to sit grumpily in his own cabin. On the rare occasions that he did chance upon the deck for a stroll, he would reduce to an insect on whosoever his glance might fall.

Every day during meals, B used to sit by my side. He is what you may call a ‘Eurasian’. But he has perfected the art of whistling like an Englishman and standing with feet apart, hands in pockets.

His regard for me was a kind condescension of sorts. One day he began in a pompous tone, “Young Man, I hear, you are off to Oxford? It is indeed a jolly good University.” Another day, I was reading Trench’s ‘Proverbs and their Lessons’. He came, and whistling all the while, flipped through a couple of pages in the volume and uttered, “Hmmm, a good book indeed.” How fortunate for Trench!

It took us about five days to reach Suez from Aden. Those who travel to England via Brindisi have to disembark at Suez and board the train to Alexandria; where a steamer would wait for them to reach Italy, crossing the Mediterranean. We were overland travelers, hence we had to get down at Suez. We three Bengalis and one Englishman rented an Arab boat. One had to look at the boatman to realize the extent to which man’s ‘divine’ appearance could descend into the beastly. His eyes had the likeness of a tiger’s, complexion, pitch dark, low brows, and thick lips—quite intimidating to say the least. The other boats were asking for too much, and this fellow agreed to take us for a lower fare. B was reluctant to travel in his boat as Arabs were not to be trusted—they could stab you without a pretext. He also recounted a few dreadful stories about Suez. Be that as it may, it was this boat that we boarded.

The boatman could speak and understand broken English. We had safe travel for a while. The Englishman who was traveling with us had some errand at the Suez Post Office. However, the Post Office was rather far off, and it would take a long time to reach. But the boatman’s objections were cast aside. After we crossed some distance, the boatman again asked, “Do we have to go to the Post Office? It will take more than a couple of hours to reach.” Our ill-tempered Britisher got irked and yelled, “Your Grandmother!” the boatman suddenly flared up and retorted, “What? Mother? Mother? What mother, Don’t say Mother!”

It seemed to us that he might just throw the Englishman into the water in his rage. He asked again, “What did say?” The Englishman held his ground and repeated, “Your grandmother!” We felt probably there was no escaping fate now. But now even the Englishman realized that the situation was not in his favor, and so he tried to explain in a somewhat mellowed tone, “You don’t seem to understand what I say!” and desperately tried to prove that invoking “grandmother” was not derogatory. Upon which, the boatman abandoned English altogether to yell “Byas—Chup!” (Enough—Shut up!) The Englishman, at his wit’s end, was robbed of words. Again, after some distance, he asked, “How far are we from there?” This had the effect of adding fuel to fire. The boatman, still livid with rage, shouted, “Two shillings give, ask what distance!” So, we came to understand that in the land of Suez, when you are paying merely two shillings for fare, you better keep such curiosities in check.

While the boatman was reprimanding us roundly, his fellow boatmen were greatly amused. They exchanged looks and were grinning, highly entertained by our ill-tempered boatman and his antics.

On one side, the scolding boatman, and the grinning fellow boatmen on the other. As we could fathom no way we could take our revenge on him, the three of us also burst into laughter. In tight situations such as this, it’s your sense of humor that comes to your aid.

Translators Note

On the later recollection of this first voyage of a seventeen-year-old youth, Tagore regarded his state of mind as one where the fertile land of his personality was replete with thorns—prone to poke at everything that came his way. He felt the correspondences penned during this phase as expressing more audacity, expecting kudos from his readers, rather than something more substantive. To a mature Tagore, on reflection, his own attitude during this time appeared as if to boast of one’s individuality or superiority over the run-of-the-mill average visitor. Looking back at his attitude during this time, the wise poet observed it to be dominated by an urge to set one’s superior individuality apart from the so-called mediocre visitors.

Hence, upon retrospection, Tagore deemed the letters disrespectful toward the countries he had visited. Also for the poet, his younger self who composed the letters seemed naive in his perspective of the world. And so, he never agreed to have these letters published

In spite of all their flaws, however, one justification that Tagore believed, could be offered in favor of Europe Probasir Potro is its language. It was probably the first prose matter in Bengali literature written in the colloquial tongue.

To read the first episode of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following page of The Antonym:

To read the next part of the first letter of Europe Probashir Potro, read the third episode by visiting the following page of The Antonym:

To read the fourth episode, fifth episode, and sixth episode which are the English translations of the 2nd letter and the 3rd letter from Europe Probashir Potro, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

Lovely translation, fluid language, appropriate cultural references and precise use of words!