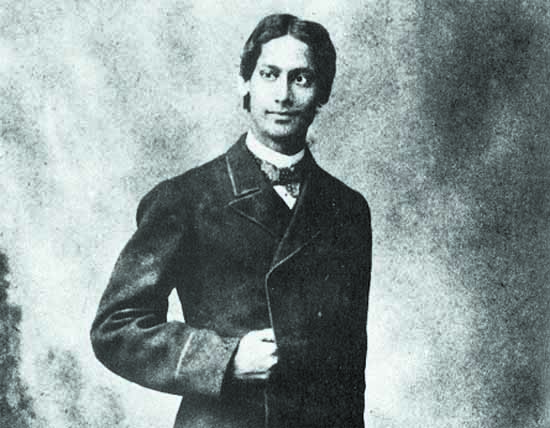

This is the fourth installment in our series on a selection of the journals and correspondences that Rabindranath Tagore had penned during his visits abroad, particularly, in Europe. Below, we have the seventeen-year-old poet’s eloquent description of his first voyage to Europe, undertaken in 1878. Some of the descriptions were reproduced partly in the autobiographical Jeevan Smriti and in the correspondence Europe Probashir Potro (Letters from Europe). The second voyage to Europe, undertaken twelve years after this (1890), is similarly chronicled in Europe Jatrir Diary.

Our first piece in this series was a seriocomic episode from Tagore’s maiden stay in England. As Majid Mahmood (2020) notes, the details of this first Europe journey are rather scarce, except for the poet’s own version. Hence, in chronicling this part, we have no other recourse open other than to refer to Tagore’s letters Europe Probasir Potro, addressed to Jyotirindranath Thakur. According to Tagore’s biographer Prashanta Kumar Pal, the letters were started on the ship and were concluded after reaching Brighton (Mahmood 2020).

Finally, a unique style of the narrator here is the effortless back and forth between the present tense and the past—which we have tried to retain. The following is the translation of the 2nd letter from Europe Probashir Potro. To read the 1st letter, which was published in two parts: click here to read the first part, and here to read the second part.

Letters From Europe— 2nd Letter

Translated from the Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta

A Look At England And Its People

Before coming to England, I used to entertain the idiotic notion that this measly island must be reverberating on all sides with the oratory of Gladstone, Max Müller’s Treatise on the Vedas, Tyndall’s theory of science, Carlyle’s profound thoughts, Bennett’s philosophical time, and so on. Fortunately, I have been disappointed with this count. The women here are fully engrossed in their pursuit of beauty and fashion just like the men who seem to be completely immersed in their professional engagements. The humdrum business of daily life goes on as usual, with political issues as the only excitement. Women are curious about whether you went to a particular ball or if you liked the concert—the fact that the theatre company had a new actor; or about a certain band playing at such-and-such place, and so on. The gentlemen ask your opinion on the Afghan War or about the special welcome Marquis of Lorne received from Londoners, or they comment that today was a fine day and yesterday was miserable, and so on and so forth.

Young women here play the piano, sing, bask at the fireside, read novels reclining comfortably on the sofa, engage in casual conversations with the guests, and whether needlessly, or purposely, flirt with young men. The spinsters here are extremely efficient. Temperance Meeting, Working Men’s Society, you name an Association, they are invariably there and are heard. Unlike the men, they do not need to attend office, nor do they have to bring up children like other women, on the other hand, they are too aged to go dance in a ball, or flirt, to spend time, so they can engage in many worthwhile activities, and probably it benefits society as well.

This country houses a wineshop at every step. On the streets, I see shoe stores, tailoring shops, meat shops, or toy shops at every step, but never a book store. We needed to buy a book of verses but had to place an order from a toy seller as we failed to spot a bookstore in the vicinity. My earlier impression had been that just as butcher’s shops, bookstores too would be an essential element in England.

What is the first thing you would notice about England? It is the extreme hustle and bustle of its citizens. It is so amusing to watch the people hurrying on the street! Umbrella tucked under their armpit, they trot hurriedly unaware of the people around, anxiety writ large on their faces as if in a constant race to not let time outwit them. The whole of London is a maze of railway tracks, with a train passing every 5 minutes.

While traveling to Brighton from London, we noticed trains huffing and puffing every moment above us, below us, and beside us, just like London’s people. In this slip of a country where one would be scared to take a couple of steps lest it lands in the sea, the use of having so many trains is beyond me. Once, we had missed the train to London, and lo and behold! The next train arrived within half an hour before we could even contemplate going back home.

The people here are not Nature’s spoiled children. England doesn’t let anyone sit back in idle leisure. For one, the soil here does not easily yield to a scratch of the hoe like in our home country. Then there is the cold. Here people need an inordinate amount of clothing—again, you cannot survive here if you eat less, you need ample food to keep warm. So people here need clothes, coal, and food in excessive amounts, and on top of it, they need liquor. Whereas in our Bengal, food is minimal, as indeed are clothes. In this country, only the one who is powerful can hold their head high, there is no succor here for the weak—neither will nature provide comfort, and to top it all, there is the fierceness of competition in the workplace.

I am gradually getting acquainted with some local people here. An amusing thing is that the people here take me as a complete dullard. Once I went out with Dr—’s brother and we chanced on some photographs in front of the shop. He took me there and started expanding on the photographs—explaining that these photos were not drawn by human hands but produced in a machine. In no time, quite a crowd formed around us to witness the comedy!

Then he took me to a watch store, where he started to convince me how wondrous a machine the clock was! Miss— had asked me at an evening party whether I had ever heard a piano play before. These people can perhaps even draw a map of the other world—but know absolutely nothing about India. They cannot imagine there may be other countries that are different from England. The common people’s ignorance here on many subjects is unbelievable, let alone India.

Translator’s Note

On the later recollection of this first voyage of a seventeen-year-old youth, Tagore regarded his state of mind as one where the fertile land of his personality was replete with thorns—prone to poke at everything that came his way. He felt the correspondences penned during this phase as expressing more audacity, expecting kudos from his readers, rather than something more substantive. To a mature Tagore, on reflection, his own attitude during this time appeared as if to boast of one’s individuality or superiority over the run-of-the-mill average visitor. Looking back at his attitude during this time, the wise poet observed it to be dominated by an urge to set one’s superior individuality apart from the so-called mediocre visitors.

Hence, upon retrospection, Tagore deemed the letters disrespectful toward the countries he had visited. Also for the poet, his younger self who composed the letters seemed naive in his perspective of the world. And so, he never agreed to have these letters published

In spite of all their flaws, however, one justification that Tagore believed, could be offered in favor of Europe Probasir Potro is its language. It was probably the first prose matter in Bengali literature written in the colloquial tongue.

To read earlier episodes of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

To read the next parts, which are the part one and two of the English translation of the 3rd letter from Europe Probashir Potro, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments