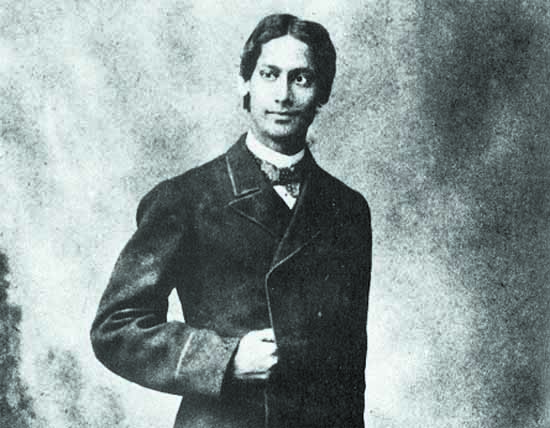

This is the third installment in our series on a selection of the journals and correspondences that Rabindranath Tagore had penned during his visits abroad, particularly, in Europe. Below, we have the seventeen-year-old poet’s eloquent description of his first voyage to Europe, undertaken in 1878. Some of the descriptions were reproduced partly in the autobiographical Jeevan Smriti and in the correspondence Europe Probashir Potro (Letters from Europe). The second voyage to Europe, undertaken twelve years after this (1890), is similarly chronicled in Europe Jatrir Diary.

Our first piece in this series was a seriocomic episode from Tagore’s maiden stay in England. As Majid Mahmood (2020) notes, the details of this first Europe journey are rather scarce, except for the poet’s own version. Hence, in chronicling this part, we have no other recourse open other than to refer to Tagore’s letters Europe Probasir Potro, addressed to Jyotirindranath Thakur. According to Tagore’s biographer Prashanta Kumar Pal, the letters were started on the ship and were concluded after reaching Brighton (Mahmood 2020).

Finally, a unique style of the narrator here is the effortless back and forth between the present tense and the past—which we have tried to retain. The following is the continuation of the 1st letter from Europe Probashir Potro. To read the first part of the letter, click here.

Letters from Europe— 1st Letter

Translated from the Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta

Alexandria

The train tracks were lined with green fields on both sides. Occasionally a few date palms would show up bursting with fruits. One could spot wells and houses sparsely scattered—cubic in shape, made entirely of solid walls with only a window or two, these houses were cubic, hardly had pillars or balconies, and utterly lacked aesthetic charm in any way. I had imagined Africa as a sterile desert end to end, but these surroundings soon proved my preconceived notions wrong. Rather, the sight of the morning dawning among the bowers of date palm adorning the green fields had me mesmerized.

The ‘Mongolia’ steamer was waiting for us at Alexandria port. Now we embarked on the Mediterranean. I had started feeling rather cold. However courtesy of the Suez, dirt had penetrated our bones. So, I took a deep bath. And we went out again for a small tour of the city of Alexandria. A boat was hired to get us ashore from the ship.

The boatmen here are veritable reincarnations of Sir William Jones. They can carry out passable conversations in Greek, Italian, French, English, and so on. I learned that French was the most commonly spoken language here. The names of the roads, shops, and signboards were mostly written in French. Alexandria seemed like a prosperous city with a bewildering variety of people from a myriad of countries and markets of various kinds. The streets were stone paved—which kept them clean but turned the traffic excessively loud. The city was indeed impressive, with massive buildings and large shops. The port itself was enormous and housed numerous ships. We could spot all ships belonging to all races including the Europeans and the Muslims, but not a single one belonging to the Hindus.

Italy (Brindisi)

We reached Italy in five days, around two in the night. Abandoning our cozy beds, we moved to the deck of our ship with our belongings. It was a moonlit night. I felt cold. Facing us was the town, silent with its windows and doors shut—all in deep slumber. Suddenly, a commotion stirred the passengers. We were told that there was a train to our destination, and the next moment, the information was reversed. In the middle of all this, an Italian Officer showed up and began counting us—a rumor went abuzz that this counting must have some serious connection with our boarding ‘the train’. But in the end, we were informed that the train which indeed existed, was to come not before 3 the next afternoon. Passengers were highly incensed. Eventually, we had to take shelter at a hotel in Brindisi.

This is how I stepped for the first time in Europe. Before visiting any new country, I conjure it in my imagination with such grand novelty that when I set foot there in reality, it doesn’t really seem as enchanting or new. Everyone was astonished that Europe had failed to surprise me.

It was 3 a.m in the night when we finally retired to bed in the Hotel. The next morning, we hired a rickety carriage with an equally beaten-up horse and went about the city. The seemingly ancient carriage and the animal which was at least fifty years old were both in ridiculous contrast to the coachman himself, a young lad of hardly 14 years of age, whereas the cart and horse seemed to be prehistoric.

Brindisi was no different from your average small town with markets, mansions, and streets. Beggars at their trade, people gossiping in small groups at the local bars, some loitering by the road chatting away. People moved with emphatic nonchalance on their faces and an elephantine sloth, utterly unaffected by the worries of the world. As if the entire town was on a vacation. The streets were only sparsely crowded with people and traffic.

We had proceeded some distance when a youth, a watermelon in his hands, stopped our cart and jumped beside the coachman. B remarked, “This must be a ploy to make some easy money.” The fellow pointed to random structures and kept on commenting, “That is the Church, that is the garden, that is the stadium,” and so on. However, we would not have missed a great deal had those commentaries not been there in the first place. No one had told him to ride our cart, or expressed any curiosity about anything, we had to compensate him for his unsolicited favor.

We were taken to a fruit orchard, hosting a bewildering variety of fruits. On every side, lush bunches of grapes smiled at us. Between the two varieties—white and black, I found the black ones sweeter. Trees were laden with apples and peaches. An old lady (probably the keeper of the garden) approached us with an assortment of fruits. We did not pay her any attention, but she definitely knew the trick of selling. As we were strolling around, a beautiful young girl accosted us with some fruit and flower bouquets, and we did not have the heart to refuse.

Italian women are truly beautiful, with a lot in common with Indian girls. Their complexion is beautiful, with lustrous black locks, dark brows and eyes, and lovely facial contours.

We left Brindisi around three by train. Lavish grapevines on both sides of the railway track were a beautiful sight to behold. One could see hillocks, rivers, lakes, hutments, fields, and small villages… all the precious stuff of which a poet’s dreams are made. I was absolutely charmed as a distant town with its palace domes, the church steeple, and picturesque houses slowly revealed itself from the lush greenery… I will never forget the sight of that exquisite lake at the feet of the hill, surrounded by lush foliage, evening reflecting on its water. It was all too beautiful beyond words, and I shall not even try to describe the scene.

Paris

We reached Paris in the morning. What a dazzling city! Looking at the overwhelming bevy of skyscrapers, one would think that there were no poor people in Paris.

To me, it seemed quite absurd to have such massive, imposing buildings built for humans who hardly measure up to 5 feet and a half. We went to a hotel, the arrangements were so lavish that it felt almost embarrassing and uneasy—just as one feels in oversized clothes.

We were left dumbfounded by the abundance of its memorials, fountains, gardens, palaces, stone-paved streets, vehicles, horses, and teeming people.

As soon as we reached Paris, we were taken to a ‘Turkish Bath’. It started with sitting in a stiflingly hot room. People sitting there began to perspire, but not me. So I was moved to an even hotter room, which was like a furnace, and my eyes started burning. I could not endure this heat for more than a few minutes and started sweating profusely as soon as I came out.

After this, I was lain down in another room. Then appeared giant of a man, who started massaging my whole body. He had little clothes on, and I could not help but appreciate his beautiful muscular physique as described in the Sanskrit shlokas: Byurhorosko brishaskanda shalprangshurmahabhujah.[1] I thought to myself that there was little sense in employing such a gigantic cannon to subdue an insignificant mosquito like myself.[2] After having summed me up, he observed that I was reasonably tall, and only had to achieve some girth to be counted amongst handsome men.

For an entire half-hour, he pummelled my whole body to purge me of all the dirt that it might have accumulated since birth. Afterward, satisfied with his handiwork, he took me to another room and gave me a thorough cleansing with warm water, soap, and a sponge. Next in another room, I was sprayed with spurts of hot water first and then abruptly a gush of ice-cold water.

The alternating sprays of hot and cold water were followed by a contraption that was erupting needles of cold water from the top, from the bottom, and indeed, from all other sides.

I could hardly endure the ‘water machine’—it was as if the blood in my heart would freeze—I surrendered and came out of the bath gasping. There was also a swimming pool on one side, they asked me whether I would like to swim. I declined, but my companion was all for it. Seeing him swim, they remarked among themselves, “Look how strangely they swim, just like a dog!” This was how our Turkish bath ended. I realized that going to a Turkish bath was no different than taking your body to the launderer.

Afterward, we hired a car that would charge a pound for the whole day. We went to the Paris Exhibition. Now you must be anticipating a voluminous description to follow.

But I was so disappointed! Just like learning at Calcutta University, we had looked at everything there was to look at in the Exhibition, but we failed to see anything truly. Our stay in Paris was just for a day—and it was utterly impossible to cover the massive exhibit in one day. Our efforts to do so only fuelled a desperate thrust to see more, which was not to be. It was a veritable metropolis on its own—and I would have dared to describe it if only our stay had lasted about a month.

My recollection of the Paris Exhibition is a massive mound—not a systematic display. Overall, all that I recall is that we saw an infinite number of beautiful artwork in the Art Gallery, and an equally infinite number of sculptures and statues at the Sculpture Gallery, and so on… but I can recall very little of it all. Then we came to London—I have rarely seen such a depressing, damp, dark place—all engulfed by smog, cloud, rain, fog, mud, and a mass of utterly busy people. I was in London for only a couple of hours but heaved a sigh of relief when I finally left the city. My friends said that with London, it is rarely love at first sight, rather, you can come to appreciate it only when you have spent some time there and have come to know it well.

Notes:

[1]The one with a wide chest, shoulders as strong as a bull, and hands as long as sal tree.

[2]A variant of a Bengali saying: Mosha maarte kamaan dagaa, which means ‘to employ a cannon to kill a mosquito’.

Translator’s Note

On the later recollection of this first voyage of a seventeen-year-old youth, Tagore regarded his state of mind as one where the fertile land of his personality was replete with thorns—prone to poke at everything that came his way. He felt the correspondences penned during this phase as expressing more audacity, expecting kudos from his readers, rather than something more substantive. To a mature Tagore, on reflection, his own attitude during this time appeared as if to boast of one’s individuality or superiority over the run-of-the-mill average visitor. Looking back at his attitude during this time, the wise poet observed it to be dominated by an urge to set one’s superior individuality apart from the so-called mediocre visitors.

Hence, upon retrospection, Tagore deemed the letters disrespectful toward the countries he had visited. Also for the poet, his younger self who composed the letters seemed naive in his perspective of the world. And so, he never agreed to have these letters published

In spite of all their flaws, however, one justification that Tagore believed, could be offered in favor of Europe Probasir Potro is its language. It was probably the first prose matter in Bengali literature written in the colloquial tongue.

To read earlier episodes of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

To read the next parts, which is the English translation of the 2nd letter and the first and second parts of the 3rd letter from Europe Probashir Potro, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

খুব স্বচ্ছন্দ অনুবাদ চলেছে। অল্পবয়সে ভয়ানক অ্যাটিচ্যুড ছিল গুরুদেবের, এ ব্যাপারটা তেমন জানা ছিল না… LOL! 😂😂

Thank you Dada for the refreshing & original take on the series!!!

This is a precious translation, as it might find readership in Europe too. Very well done.

“Europe Jatrir Diary” o ki translate kora hoechhe, very eager to read that as well.