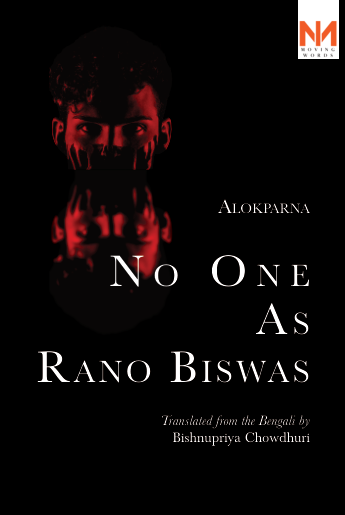

TRANSLATED FROM THE HINDI BY RITUPARNA MUKHERJEE

PART 1

The girl was quite dark. Frustrated with her complexion, she brought back a fairness cream from the market that would work wonders in three weeks. Although she was patient enough to actually wait out three weeks before any substantial results, she saw her complexion improve slightly after a week of its use. And the matter begins its course from here on. She felt that she could now live her life with all its enjoyment. And her lies gathered double the steam. Earlier, where four out of the ten things she uttered were falsities, now, only one or two were really true. For instance, if she had the physics exam the next day, she would tell Ija and her high-shouldered tutor that she had English exams. She would even prepare for the English exam with her tutor’s help and to balance the scores, she would study physics ahead of her English test. Her results were obviously left to God and she would pull a serious face as if promising Ija and her tutor to work harder for her next exams, her expression having an impact on all but herself.

Eva Karnik had oily skin. Everywhere, aside from the area bordering her lips. And this non-oily part would shrivel at the slightest touch of dry air. As a result, Eva Karnik had to run to the mirror most often and check whether a moustache had made an appearance since morning. And yet another time. She didn’t have a moustache per se but the fine, bluish hair on top of her lips, that remained mostly invisible, in days like that would stick to one another and paint a thin blue line on top of her lips. And therefore, every movement of her lips, talking, smiling, guffawing, everything would jangle. It would take her two or three days to set things straight in that area, to tame it, make it soft again with oily home remedies, masks and potions. And Eva Karnik would become a girl again.

This girl was like the solitary dusks of certain days. Eva Karnik, class 10, whose right braid hung a little lower than her left, was busy sharpening her pencil quickly, when the high-shouldered man entered the room. Eva Karnik should have stood with the same rote tone of voice and then sat down in the next moment itself without anyone’s permission.

He was her tutor. Master was not really a popular word so he preferred the word ‘Sir’, and was remunerated two thousand rupees per month. Eva Karnik would excuse herself out of the room when he would be given that envelope. He was a strict tutor. He would really hate certain things, something that Eva knew by heart. In those two hours she didn’t have the slightest respite, not even to move her strained neck and make it a little better. She would whisper the answers she knew quite well and mark the places she knew quite well with a pencil. So, when it was the season of thin moustaches on her non-oily skin patch, things wouldn’t jangle even once. Because she neither moved her lips, nor spoke, nor smiled and there was obviously no question of guffaws!

The last fifteen minutes were allocated for her. For her questions. For the lessons taught that day. And at that moment, she would feel like an amateur puppeteer, who was suddenly given all the puppet strings to control, who had to prove her mettle at that instant, who, in reality, didn’t have the slightest inkling of which string to move to exactly what point to make the puppets dance to her tune. Some recess of her mind would miraculously recall some lesson she had learnt three or four days back. This was why she would ask a question from chemistry after a lesson in geography. This confusion would, however, make one thing very clear that although she felt that she didn’t really hear anything, she would actually end up listening. Otherwise how could one explain the presence of conceptual understanding now, with a question tagged behind its back, something that was made three four days back! She was so well-versed with it all that she would get an answer on chemistry after her geography lesson from the one sitting opposite her.

Listening to her tutor’s answer, she would ponder about her question, when the hands of the clock would happily signify to her the completion of their breathless journey of fifteen rounds across the clock face. She would stand up. The strict man next to her would move across the partition to the drawing room sofa area and eventually outside and she would move inside the tunnel-like house.

The woman called Ija could be said to be fully caged within the white color vise—her age, her hair, her clothes, her activities. She wouldn’t touch sarees if they weren’t starched and ironed. Most of her time was spent on pulling the sofa covers back to their place, zipping the television covers shut, pruning the yellow leaves on the vase, or straightening the carpet made askew by hurrying feet. The maids weren’t stable in her household. None of them would stick beyond a week or two. She meticulously supervised the cleaning of her floors, eking out dirt from the corners, or the scrubbing of iron utensils until they would shine. And what then! The household wouldn’t lack anything in the transition time from one maid to another, because she would flawlessly execute every kind of work.

Although she had begun her awareness of the world beyond under her husband’s guidance when she would identify India on a globe, she had now gone so far ahead in her experience of the world, that she could separate the grain from the chaff in moments of looking at the people around her.

Her favored instruments were the five-rupee hairpins and the four-rupee safety pins. The saree that she put on was kept in place with the safety pin, something that would be undone only during her shower the next day. This was the case with the hairpin as well. These two objects would be on duty even when she slept at night.

She had brown eyes and matching that color she would cloak her white hair with the golden-brown color of Garnier hair color shade 4. Her alertness indicated that perhaps she lay in wait for something significant to happen to her, as if she was aware that someone could knock at her door any instant. But because she hadn’t heard fate knock at her door yet, she could only imagine it being like that, as if it were real. Sitting on her armchair with her eyes closed, she could understand by the knock who she would see on opening the door without looking at the person! Which sound belonged to the milkman, which to the newspaper guy, which was made by the barber, which by Eva Karnik, and which by the high-shouldered man. And this, in actuality, was one of her favorite means to pass her time. To identify each strike of the hand and to congratulate herself on opening the door and to wait for the next strike thereafter. And the reason for this was the fact that a calling bell had never made its way to either the left or the right of her front door.

The high-shouldered man was known in the world by the name Vikram Ahuja. While coming in and getting out of the house, his head would always touch the door frame. One, because the height of the door was low and two, because each door had an ankle-height threshold. Besides, there was also his uncommon height to consider. He always wore white running shoes. His gait, speech and breath had a certain stubbornness about it.

His past was marked by two lovers. His first love, Gauri Karmakar, was like first murmurs, a tale of the same college, same class, same subject, same road that led home. It had the thrill of landing on some other peninsula. It had the sweet satisfaction of patient labor, like detaching the peanut shells. The incident had the tenderness of opening petals, something that others did not spy. Similarly, it withered like a flower as well, without a specific explanation for fading away, just that the world would suddenly come to know that the flower had shriveled, or perhaps it might not come to know anything about it at all.

The second came after life had turned sideways for a few years. One day, deep into the evening, an unusually bright-skinned girl came to him, her skin aflame. All the information in her computer had become corrupt and she didn’t have a backup. Two girls had come to the office for some project. One had Indian skin, the other—this girl—had the exceptionally fair stock like that of one abroad. Fate was with Vikram Ahuja that evening. Twenty-five minutes of fretting and guesswork later, he was able to do something which he himself had no expectation of. The girl’s complexion became bright again, the color draining off her face.

Their next two meetings after that evening were purely because of the girl’s initiation. One, the day right after when she had come to thank him personally and the second, the evening before she finished her work and returned, when she came to demonstrate her work and to obtain a formal permission to leave. The next few meetings laid bare a few secrets. The girl was Irish and she would round her lips to articulate Hindi words. When she would speak unmindfully, the words would tumble scattered from her mouth and when she would utter things consciously, the words seemed to climb on top of each other. She remembered the rusty folktales of her society. Although if one paid too much heed to her mispronunciations, those tales would evoke more laughter than suspense, but if the roundness of her pale-skinned eyes became one’s only truth, then the stories conjured nothing but mystery and romance. The rest were lies.

She would mumble something in her language while straightening out a candle in the church, and when asked the meaning of that later, she would smile, dimples on her cheeks. She knew how to excite life without doing much really—while jumping to ring the temple bells for instance, or while hissing through her tongue when it touched her inner cheeks because the panipuris were too spicy, or deliberately creating ripples in the monsoon puddle in street corners with her sandal. She would never tire of listening. And she was dangerously fond of forgiving others. She would always work with a smile whether it was the first evening when she had asked for his help or while broaching the topic of getting back to her country because she had completed her project that last evening. Vikram Ahuja had also smiled in reply. He felt as if he had touched a mass of clouds for some time, however little.

Eva Karnik had never really liked her hair. Straight till her shoulders, they tangled in messy curls underneath. Perhaps one reason could be the tight braids she had to put her through for school. The hurry in braiding her hair didn’t help much either and they would often come out a little lopsided. She would unbraid them the first thing on getting back home and would go for her evening lessons with uncaged hair. But what would happen is her hair would come in the way when she peered into her book, trying to understand the lesson. She would gather them all and tuck them neatly behind her ears and by the time her hands reached the page, out they came again. The longest strand of her hair would wave enticingly on the page in the farthest corner. The high-shouldered man would raise his neck in her direction and Eva Karnik’s meandering heart would startle and come right back to its place, apprehensive of an emphatic rebuke. Vikram Ahuja changed his mind immediately after parting his lips and the girl had to be content without the reproach.

The tutor thought that the girl opposite him just pretended to understand and although he would get extremely irritated by these pretenses, he always failed to understand why he could never really scold her. when he sprung a question between lessons, the girl would squint her brows and try hard to recall something. Everyday he would make up his mind to complain to Vasundhara Karnik about the girl, apologize for not being able to come anymore, when he would step out to the other side of the partition after the lessons. He would even frame an introduction to his statements, but would always be deterred by the normally snappy Vasundhara’s insecurity about this matter. Even if he could utter a grievance or two, he never quite managed to reach the part where he wanted to discontinue. And what was the point of complaining when he wouldn’t leave!

He suspected that the girl was aware of his dilemma. And that was why she had given herself the right to be entirely playful. When the eyes of the high-shouldered fellow would rest on the girl’s face near him, who seemed absorbed in listening to his explanations, his delusion in her concentration would quickly come apart when he would spy her fingers carefully tearing a piece of paper into tiny bits. Seeing her tutor’s eyes, she would immediately stop her busy hands.

The half torn and fully torn pieces of paper would then be kept on the sofa beside her with equanimity. Her mind would race speedily but her body wouldn’t betray a clue because she reigned it with an iron fist, because she could keep herself calm despite her mind. Because the sole of her right foot was in the extremities, her entire body would concentrate on the book in front while her right foot would shake to a rhythm of its own. Sometimes, in what seemed like half a respite, one of the tiny pieces beside Eva Karnik on the sofa, would float in the incoming breeze and then she would lose the tight control she had on herself and she would watch with fluttering lids the tiny piece flap and play around till it fell ignominiously in one corner. Vikram Ahuja would wonder meanwhile that had the girl been two or three younger he would use all of his five fingers to slap her to quell his frustration a bit.

It was the guardian meet after the pre-board result. He came to know the evening before that he had to be present as the girl’s guardian. Vasundhara Karnik broached him with a proposal that floated more like a plea in the latter half. He felt himself incapable of both agreeing and disagreeing. He just had one harangue—what was his place among a group of parents! Vasundhara Karnik, being an able woman, had already secured the school’s permission to send him in her place due to her illness. He could not sit there any longer.

No sooner did he stoop at the doorstep to wear his shoes than Eva Karnik came as fast as droplets rush to the earth. Almost out of breath. Telling him what time to report the next day. Tying his shoelaces, he listened with his head still bent. A pair of eyes looked at his own as soon as he rose up. Eva Karnik whispered without batting an eyelid— ‘Wear your blue shirt and black jeans.’ The eyelids of the high-shouldered man did flutter however. The girl was gone.

Also, read a Hindi fiction by Indira Dangi, translated into English by Rituparna Mukherjee, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments