She wrote her responses to the questions asked, was worried that her answers got too abstruse and critical at places. May be they were.

But, we felt, some answers, worth listening to, could just as well be difficult, take more than flickering attention required for swiping left, right, up and down. Instead, it should take some reading, re-reading, thinking that wreaks havoc—you know all that old-school stuff…

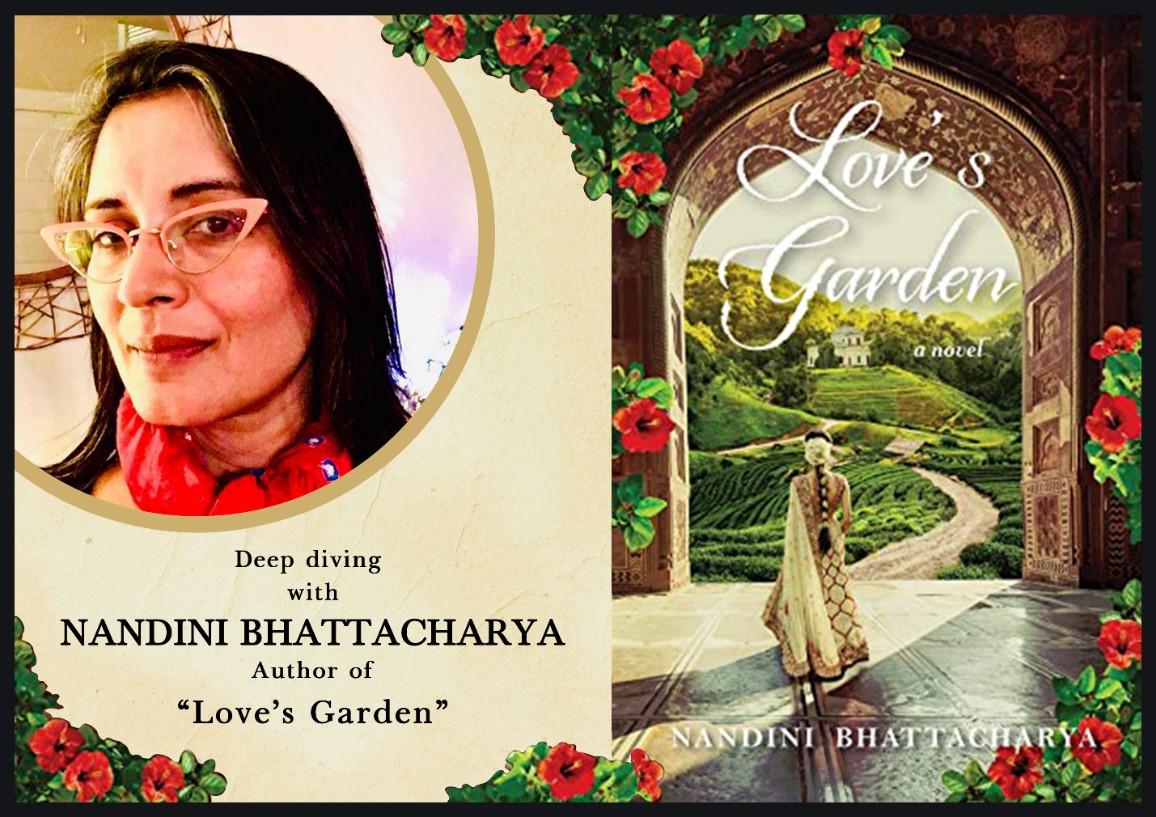

Our featured author of this issue, Nandini Bhattacharya who was born and raised in India and called the United States her second continent for the last thirty years. Her short stories have been published or will be in the Saturday Evening Post Best Short Stories from the Great American Fiction Contest Anthology 2021 (forthcoming 2021); the Good Cop/Bad Cop Anthology, Flowersong Press, 2021; the Gardan Anthology of the Craigardan Artists Residency, Meat for Tea: the Valley Review, Storyscape Journal, Raising Mothers, The Bacon Review, The Bangalore Review, OyeDrum, and Ozone Park Journal. She has attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Workshop and held residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, VONA, Centrum Writer’s Residency, Ragdale Artist’s Residency, and Craigardan Writers Residency (forthcoming). She was first runner-up for the Los Angeles Review Flash Fiction contest (2017-2018), a finalist for the Fourth River Folio Contest for Prose Prize (2018), long-listed for the Disquiet International Literary Prize (2019 and 2020), and a finalist for the Reynolds-Price International Women’s Literary Award (2019) and a finalist for the Saturday Evening Post Great American Stories Contest, 2021. She is currently working on a second novel about love, minorities, racism, and Hindutva politics in India and xenophobic mentalities and other mysteries in Donald Trump’s America, titled Homeland Blues. She is an ardent admirer of Jhumpa Lahiri, Megha Majumdar, Amitav Ghosh, Salman Rushdie, and last but not least, Chimamanda Adichie. She lives outside Houston with her family and two marmalade cats.

- So where does it all start?

At the beginning. With being a bookworm tucked away from the world from the time I can remember. And then years of being away from reading mostly for pleasure, as I went through the grist mills of formal education and academia. And then when I had a family, and half my life behind me, and was a permanent exile and still looking back at the motherland, the words started flooding in.

- How do you place yourself between the two continents? How many continents are there really? is there a third continent for you?

Great question. I am, not to put too fine a point on it, feeling more scattered and stretched as time passes, partly due to choices I’ve made in my own life. Maybe writing is my third continent. There I can and do have a community where anyone from anywhere and anytime can come to stay and we might all live together happily ever after. Seriously, we would all like more authenticity, more roots, whatever they might mean, but this is a world of many Diasporas (actually has been so for millennia, if you read someone like Amitav Ghosh or Salman Rushdie). So I suppose I’m trying to grow to accept that, using writing and literature as supports.

- You started off with short stories, didn’t you? Moving from there to the Novel, was it a significant transition?

No, I actually started with the novel that became Love’s Garden. I’m not sure how that works for other people, but it was that way for me. As to transitioning, I think, especially now, that the two are two different forms requiring quite distinct creative muscles. A short story is an exercise in profundity as clarity and brevity, whereas a novel is definitely a less demanding, more comfy place, at least for me, and as American novelist Henry James once said “a loose baggy monster.” Once you’ve spent considerable time being comfy, maybe you need to make visits to the gym for a while. Maybe the short story is the writer’s Nordic Track.

- Tell us a little bit about your creative process. Do you have a specific writing routine?

I have other routines, but as a creative writer not really. I feel suffocated by rules like “Get up and write three pages every morning.” They might be great for other writers, they just haven’t worked very well for me. Maybe I’m a dreamy Bengali that way. We Bengalis didn’t use to have much of a reputation for a rigidly prudential and efficient way of life. We like adda, sprawl, meandering and so on. I think my creative process is like that too.

More specifically, I write whenever, or as soon after as possible, I get an idea. Or when a sentence or image crops up in my head, wildly and disobediently. Which is entirely impractical, of course, because I have a day job, a child, a very imperious cat, a garden, a physical body that demands upkeep, family, friends, and of course all those pesky books and films to keep feeding my imagination (these not in that order, necessarily). But in truth, I actually am not a very ‘disciplined’ writer. I don’t write every morning or evening, or at midnight for three hours, and so forth. I write when I can, and also write when I must. That requires a lot of juggling and faking-till-making it, doubtless. My son calls it nifty creativity. Sometimes the time must be Sympatico with the place. I like to write when I’m in a coffee shop, a bookstore, or during residencies and retreats. I’d love to learn how to write more systematically, regularly, but so far, given the other demands on my time and maybe the way my imagination works, that has not been the case.

- Where do your characters live—in which time, which part of the world?

That entirely depends on the work, no? So far they’ve lived across continents and worlds and mentalities. I suppose all my protagonists are also me, in some sense, or having an animated argument with me. So far, though, none of them have lived on other planets or galaxies, and so on. I guess I love this planet too much (please check out my blog https://www.oneplanetonlyone.com), and am not in favor of Mars colonization as some of my friends are!

- I keep reading about your “archeology of self”. I love your choice of the word “archeology” which got me intrigued—why that and not “mythology”? I hope the question makes sense…

The question makes tons of sense, even sense I didn’t see before. Thank you for the question. First, as disciplines or knowledge systems, an archaeology and a mythology are inter-related, right? Archaeological expeditions have often led to the confirmation or resuscitation of latent or forgotten myths. Second, Roland Barthes once said that Myth is History imagined as Nature. I think he meant that mythologizing something is to give it an existence and status in the world and consciousness as not just what happened (History), but what eternally happens, is pre-given, and must happen (Nature). Turning secular, prosaic historic truth (the account of what happened) into the higher form of poetic truth (mythic narrative), which was Aristotle’s preferred form of writing. But in their very pronouncements, both Aristotle and Barthes gestured in fact at the braided nature and symbiosis of myth/poetry/truth and nature/history/truth, and so, going back to “Archaeology of the Self,” you could think of my term “archaeology” as including mythologies of the self (poetic truth, what I imagined happened to real people) balanced against “real facts,” “what happened,” “what we see here,” “what comes up when we dig” (historic truth, facts, artifacts, phenomena). I hope that isn’t too wildly abstract (or even TOO Bengali, or too abstract even for Bengalis!)

- Some suggestions for aspiring writers?

First, imagine, of course (poetry), but research, research, research (history). Write what you didn’t know, and your own wonder and excitement at discoveries will show in your writing. For my novel Love’s Garden, it was when my reading led me to stories about soldiers of the so-named ‘Forgotten Army’ in the ‘China-Burma’ or Eastern Theatre of World War II who bravely resisted Japanese aggression with no backup, and later got little attention from war historians, a sluice of empathy opened in me unexpectedly and lifted the ship of my storytelling. Not something I would have expected.

Second, think about connections, and find story ideas in discordance. Look for dominant narratives, then find the gaps and fissures in them. I was having trouble with the plot of Love’s Garden at one point, especially because of the chronological span. And my ‘archeology of the self’ sometimes made it hard for me to see the larger canvas, the wider stakes that could make the personal meaningful as a tale of wider public appeal and meaning. So, at some point, I had to leave my navel-gazing behind for a while and look into the history of the city of Calcutta (now Kolkata) in which most of Love’s Garden’s events take place, especially during the Second World War. Some of my own family members had been suppliers, contractors, and builders for the British during and around wartime (and not necessarily always very patriotically!). But my personal history could become a fortress of my own, and that isn’t how I understand individual stories or history with a capital H. Once I began reading up on Calcutta in the thirties and forties, I learned about one particular British Royal Air Force pilot who played a central role in defending Calcutta from Japanese bombing and became a beloved figure in the city despite being one of the master race, and this provided me a character in Love’s Garden who provides a hook to hang the stories of several women characters, including my central protagonist Premlata Mitter. Another character, a Japanese-American soldier, was born of accounts of the ordeals of the ‘Forgotten Army’ in Burma. History is a multilayered and multi-veined tangle of public and private, structure and events. So look around at intersections as well up the long vanishing point of highway called denouement. Take detours and find yourself making unexpected discoveries that become clues, connections and templates.

Finally, read the classics and the contemporaries in equal measures.

- What is your current project? Do you plan to come back to short fiction?

I’ve now finished my second novel Homeland Blues — this one in a very different setting but with themes that carry over from Love’s Garden — about one Neena Mathur, a young Indian widow in the US forced to face her own and her community’s deep-seated racism when her husband’s unexplained disappearance and presumed death test her Indian-American or ‘Desi’ community’s loyalty. Ejected overnight from diasporic ‘model minority’ privilege and colorism as she begins her descent into the hell known as illegal immigrant status in the United States, Neena finds a new identity in unexpected kinship with a bisexual African-American man as well as immigrants facing deportation in Trump’s America. As the story progresses, it also reveals itself as one about the systemic dehumanization experienced by India’s Untouchables or ‘Dalits,’ which mirrors that of people of color in America. Recently, Pulitzer prize winner Isabelle Wilkerson has written eloquently and penetratingly about the fact that Race in America is perhaps better described as ‘Caste,’ the system of oppression that keeps minorities downtrodden in India. Homeland Blues dramatizes this insight. Ultimately, it’s about multi-tentacled hatred and fear surrounding gender and racial traumas, but also about the love we must find to empathize with the stranger we’ve always been taught to fear.

As to short fiction, yes, I just had my story “Rowans, Oaks, and Other Trees,” accepted for the Saturday Evening Post Best Short Stories from the Great American Fiction Contest Anthology 2021 (forthcoming 2021). I also have a few other pieces in the works and seeking homes.

- Why did you choose this unique far-back and rather spread out time-line? Were you worried at all about the contemporaneity? I guess, what I want to know is if you feel the time-space where you erected Love’s Garden has any special relevance to our present time?

Well, historical fiction certainly is very undaunted, sometimes, about its scope. I mean, look at Hilary Mantel, or Pat Barker, or Amitav Ghosh. And yes, the timelessness of certain things can be the most desired connective thread for readers. However, I think we also risk assuming things about our understanding the past if we make too much of the timelessness idea. I think the past is also radically different and inaccessible, and this is something that excites me. And as to worries about contemporaneity – and of course readers liking my novel – I guess I’m a bit more worried that we could acquire a reductive and opportunistic view of the past, something that seems to be a distinct rot in the political framework today in Narendra Modi’s India. I worry more that we might not have a sufficient sense of the radical otherness of the past. I can’t exactly articulate how and where commonality and otherness intersect on the timeline of history, but I believe their intersection is what we call a historical consciousness. And that historical consciousness is really what we’re talking about when we talk about History, I think.

- Do you have a favorite section/ character in Love’s Garden?

A few, but I’ll share this one, especially apropos the statements above.

It’s from Chapter 55 of Love’s Garden

He’s desperate to find that magic spell again, to put his hands around that crystal ball of desire, that magic globe, like warm paws; keep it safe. It looks like it might begin to disintegrate.

Who am I? he thinks. Maybe he says it aloud. Patriot? Traitor? Who the hell am I?

Just then he sees her walk past, so plumed yet so fragile.

You’re lucky, Amherst you scoundrel, he thinks. You got away. You are in the Calcutta Club. Drinking the best bourbon, no doubt a salute to your country for oh so recently joining the fight. In a room with bright light, cool air, plenty to eat and drink. Beautiful women. You are alive, fella. In one piece. A pretty gal called Jolene is here, very close.

But then the sharp twist he felt in his gut when the water-run call came on the bluff comes back. Civilians are excitedly discussing the war and the battles. He is unspeakably lonely. Men of his company have been pressed back into the frontlines, he learns. They must be dying even then of dysentery, cholera, typhoid, scrub fever, gangrene, a shot to the head. Now he imagines, against his will, fighting the images, the Myitkyina men’s faces, their hollow eyes. Eyes smoky with hate or rage or simply exhaustion — he can’t tell. And Sterling’s dead.

But.

He is here.

That’s when he makes up his mind.

Why wait? One day the war will end. Who knows what new storm will gather that day? Who knows what that age will bring? Who knows what India will be? Will the British give her independence? Who knows? If not, will India shatter into a thousand pieces? Will Hindus and Muslims hack each other to death?

He’ll be gone, surely. Juniper and Ash again; the smell of Eucalyptus. The sky a tall blue arch overhead. California. The gentle waves of the Pacific, cresting softly, crashing gently. Pale gold, sandy beaches. When the war ends, he doesn’t want Jolene to be alone in India. He’s seen the black looks people are giving one another on the streets already. He’s heard about the killings here and there, everywhere. Gandhi fasts each time killing breaks out, and it stops for a bit. Gandhi sits up, drinks a glass of lemon juice with honey, and the killing starts again.

The English watch, wait… waver? They’re taking their time.

To free or not to free.

And he’s waiting too to be free from his memories, his nightmares. Free to pursue happiness. To not be alone.

Well, he’s not English. He’s American. He’s not going to wait. He’s going make a quick call.

Sometimes everything a man feels is absolutely, one hundred percent real. Every nightmare is real. Every imaginary whisper is real. Now is his time to make love as if love has been discovered for the first time. This is the way of his times, a time of keeping what one can find. This is love now.

“Hey Amherst! Look sharp, old chap. We’re off to play a game of billiards till supper time… join us old boy, won’t you?” Sunny punches his arm roughly. Sunny’s English toff talk amuses him. He goes with him.

When he sees Jolene again — she’s sipping champagne from a slender fluted glass — he goes up to her and asks for a dance. She leaves the bar, quite at ease, her hand resting lightly on his arm. The band is jamming something jazzy. They dance. She’s quiet. He’s nervous. Afterwards they stand smoking in the gardens. The moon is high in the sky and the garden lamps twinkle through the trees. The air is not dull with anguish and pain; it’s just the soft, moist breath of the Bay of Bengal.

Time. Of the essence. If he doesn’t move fast someone else will snap her up. There are too many men hanging about the clubs, restaurants and bars of Calcutta, pockets clinking, eyes glistening. Pretty girls have their choice.

He asks her to marry him.

“Tell me, Mr. Buck, do you even know my last name?”

He attempts gallantry. “Won’t you be changing it to mine?”

She smiles patiently. His attempt to be fresh. She has surely heard it all.

“But you don’t know it. And you’re asking me to marry you?”

He gropes, hopelessly, for a witty, gallant retort. He pushes back his hair, rubs his big, ugly nose.

Before it gets too awkward — though Jolene is still smiling at him — sounds of applause come from the Club. Louder music comes to them through the Club’s open windows. The band’s playing “We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when….”

The notes of Vera Lynn’s cockney contralto fill the air. The audience is singing along. Sunny trots over, pointing out the obvious. “It’s a BESA night! What fun, eh old boy?!!” BESA — the Bengal Service Entertainment Association — has been contracted to play tonight at the Club as a special treat. Maybe another minor skirmish not gone horribly wrong. Maybe a sudden off-hand noblesse oblige of the generals.

Sunny sways from side to side, belting out “We’ll meet again…,” with a girl on each arm: spritzy, feisty. Unsteady, unsober. Joyous. If his is a guttersnipe kind of joy, it is uncomplicated, easy.

For Amherst, yellow son of a father furiously disappointed in the consequences of lust, such easy joy is not possible. He was shoved to the frontlines by his father’s hot, meaty hand, no questions asked. His father had shoved him also into football in high school where a fall and a blow left him with a ringing in one ear that came back on the bluff. His father marched him up to the war recruiting office in 1941 — “’ere’s a red-blooded American boy wantsa take out a few Japs” — and saw him off on his battleship.

Mongrel. Japanese Suzie from San Francisco and Anglo-Saxon Ambrose from “down-deep” Kentucky somehow got together in Los Angeles and brought him into an America that spits him out daily like gristle in an otherwise perfect cut of meat.

He is furious, been furious, all his life. That is why he wants another story. He must have it. He wants a happy ending, two worlds mingling, not clashing.

Sunny — bless his soul — shrieks and whistles at a brief pause in the melody, making the entire room whoop and bellow. Do these people know what they’re really doing? What’s really going on? For fuck’s sake, this is a little war dance, is it? Jolene and he find themselves a few feet to lean on against a wall — now it is standing room only — and listen.

Someday they’ll be gone as if they never lived, loved, laughed or fought. They’ll be ghosts staring out of yellowing photos at people trying to imagine — or maybe not — what their lives were like.

He doesn’t want children himself but some of them, maybe, will be the children of the dancers and drunks here tonight. Maybe they will or maybe they won’t realize that the frail, antique-looking people in the old photos had been real people, quite like them, and also different. That they bled when they were cut. Just like them. That they were flesh and blood. Weak and brave. Maybe they’ll even imagine this night of warm Bay of Bengal breezes and lemony-gold chandelier light. This moment. This happy moment! Maybe they who are living in this moment will never truly be dead to the ones to come.

He wishes those children well, and he believes in them. Though that night he can’t see their faces, though they too are ghosts of the future, unknown, unborn, he wishes them long life, happy memories, wonder and delight.

Because there is still magic left in the world.

Like Vera Lynn’s song.

The dancers flow around him and Jolene like a flock of swallows. Jolene puts her hand in his at some point, and he holds it firm, sure — and hoping — that there will be blue skies “some sunny day.”

- Other than words, what else do you click with?

Cats, gardening, and the myth (in the sense of poetic truth?) of true love!

0 Comments