TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN BY JOHN TAYLOR

I have never worn a necklace. Any ornament weighs down on me, perhaps because I sense the one made of the bones entrusted to us. A whole skeleton to support. My rings are those of the spine, my bracelets the joints of the ankles and the wrists. I seek the foundations, what is solid in us, what remains. The thread that holds us together, that gives meaning to our gestures, is so thin.

“I go through this whole universe as does a thread its pearl necklace” (Bhagavad Gītā): I am reading from a sequence of fragments that Sabrina Mezzaqui has collected around the title Necklace. As in her artworks, in this sequence the voice of the other is incorporated until emerges the weave of our being, the interwoven lives that go before and through us, our “interbeing” as Thích Nhất Hạnh calls it on a page whose margins Mezzaqui has opened, delicately showing the framework that supports it.

I have gone to see her in Marzabotto. From the small station we reached her apartment in a few footsteps, went out to walk all the way to the Etruscan necropolis, then, crossing the town, entered the Sanctuary and, finally, her workshop. I have come with the void of a loss inside me. The broken thread. All the beads that strung my life together have been scattered on the ground. Kneeling on the floor, I try to pick them up as they bounce and roll away even further.

The poems of Antonella Anedda’s Save As have brought me here. Some sentences from the “Sewing” section have in fact been copied out by Sabrina Mezzaqui in her own hand and embroidered on a cloth notebook. Writing a word with a needle and thread means putting it through your body and experiencing it pinprick by pinprick. It is a work of dedication into which all the love and perseverance needed to bring something to light is poured. By keeping a word in your gestures, by acting as its go-between, a space opens up in your body that the mind cannot reach with its understanding. This is probably what transcribing means—giving one’s hands to another person’s voice, as in an act of trust, as in a prayer. Sabrina Mezzaqui’s artworks, like Antonella Anedda’s poems, come from a practice of attention born to face loss; they are exercises in listening to embrace the void and transform it.

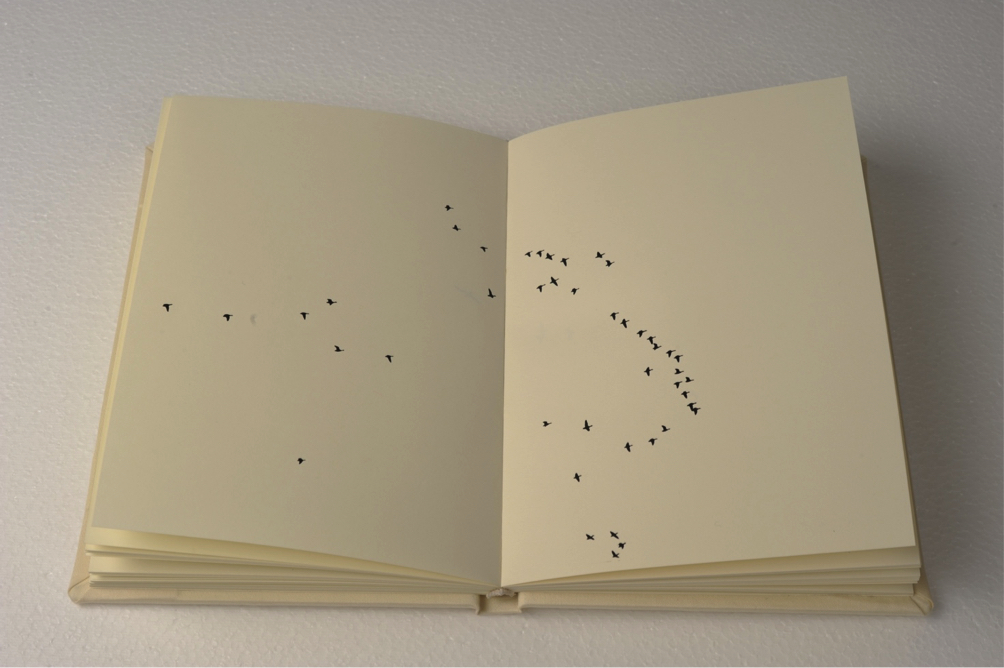

In the apartment in Marzabotto, on a small wooden lectern leaning against the wall, there is an open dictionary. A little higher, two windows frame silhouettes of houses and trees. I recognize the images of When Words Land, in which Mezzaqui reads slits of light shining through the shutters, the story of rain on the pane of glass. There is something profoundly archaic in her gaze, capable of recognizing the traces of writing in reality, of feeling the matter of words as something real, shaped by the same energy, by the same meaning that beckons. So it is in one of her works from 2006, Signs, in which a book opens, giving birth. From its white pages rise black silhouettes of flying birds, freeing themselves into space. It is the same miracle that we witness in one of the central sequences of Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia, where a flock of clamoring birds emerges from the Virgin’s womb. This open book that Mezzaqui shows us is also the sacred place of the origin. From its pages, life surges forth, its meaning which is given to us, which is up to us to decipher. But that same flight can also be read in the opposite direction: it is the birds that alight on the page, laying down their truth. It is Nature itself that writes through its forms, motions, and rhythms, making “signs” emerge along our path.

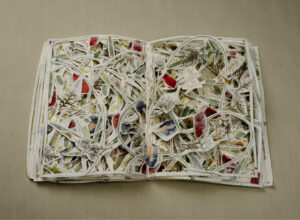

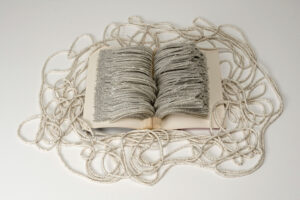

Sabrina Mezzaqui’s art is governed by something similar to obedience, an ancestral harmony, a kind of justice that every gesture is called upon to restore. We are led back to that circularity characteristic of peasant civilizations: the slow shelling of seeds like the grains of a rosary, the liturgical daily doings of an industrious community. Many of Mezzaqui’s works have been born in this way, within the patient circle of hands that have shared the work; minute repeated gestures, with a dedication that has made it possible to go across time, giving back something that has been fashioned of its own substance. Whether paper or cloth, written words or a video image, time is always the condensed matter of her works: they slowly release their energy, the gestures and the life of which they consist. It is impossible to remain passive spectators: as with a poem, the charge of meaning with which we are invested beckons us to get to work in turn, to disentangle, to gather into our hands, to care for. Her art is so humble and radical in its anonymous, original gestures that it almost blends with the effects that atmospheric agents have on things. The sensation is often that of facing the patient, methodical work of an anthill, a beehive, as if Mezzaqui were attune to the movement itself present in nature, with its cycles of destruction and re-composition. Several of her works are metamorphoses through which a book is freed from its form and returned to a meaning that lies beyond words, in the very matter of language, in that making (poiein) at the origin of any creation of meaning.

To Mezzaqui’s art belongs the time of enchantment, that suspended dimension in which, as in fairy tales, transformations and changes of state occur. We are brought back to the primordial force that supports and multiplies an individual’s gesture into that of the community which precedes him, which can be close to him. As if responding to one of her “calls” that she makes to carry out her works, we are beckoned to enter this other time together, to find the thread, bead after bead, to create our necklace. Sitting at a table, at work, as if kneeling. Holding this instant in our hands, from now on.

(October 2017)

Also, read Stories of the War by Chantal Danjou, translated from the French by Dominique Hecq, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments