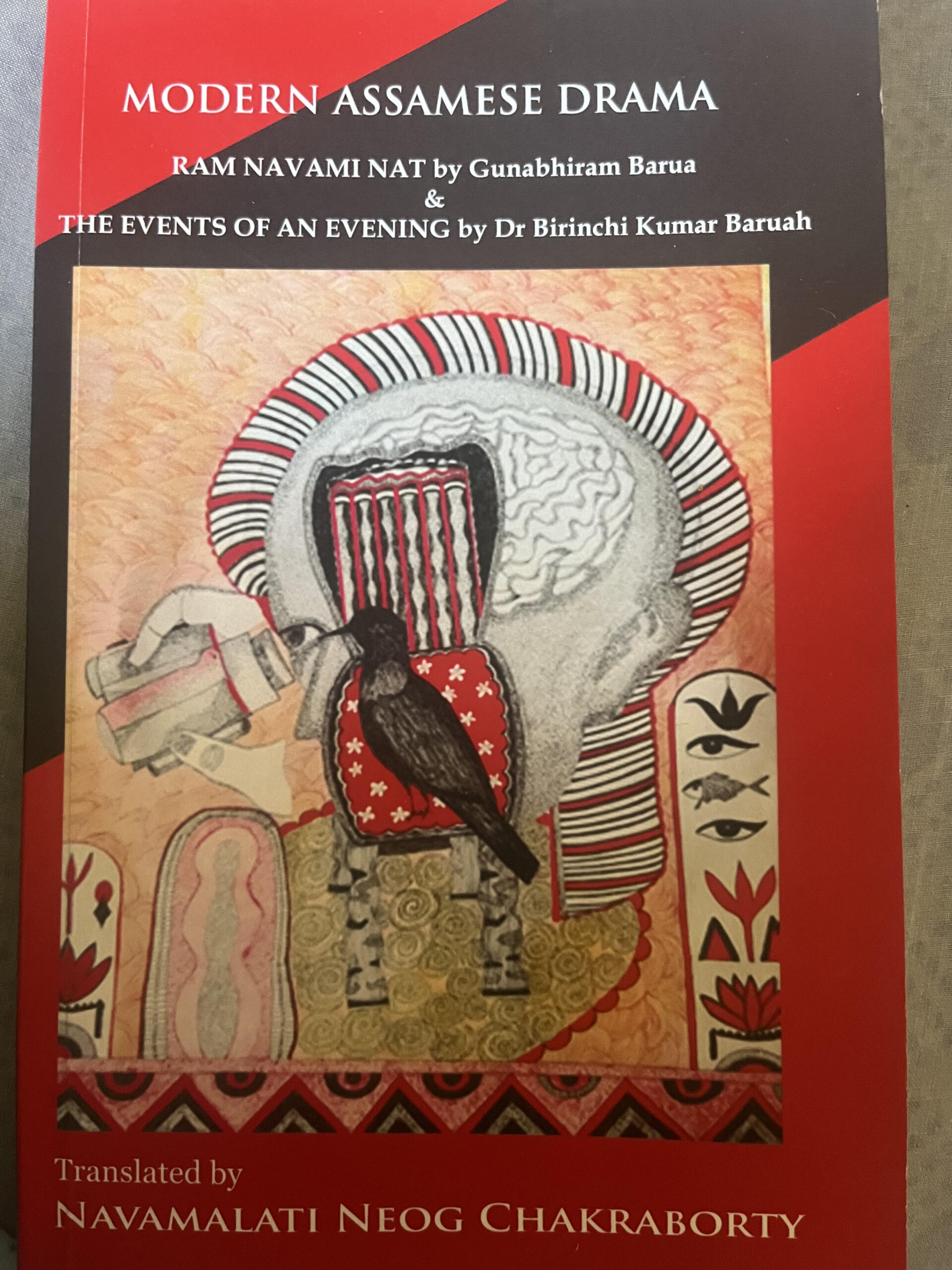

TRANSLATED FROM THE ASSAMESE BY NAVAMALATI NEOG CHAKRABORTY

REVIEWED BY AMANITA SEN

In the section titled ‘A Nuanced Understanding of the Assamese Drama’, of the book that is being reviewed here, the translator Navamalati Neog Chakraborty refers to an interview of Sharmila Tagore, the famous actor of India, where she mentions that her maternal grandmother Latika Thakur (granddaughter of Dwijendranath Thakur, Tagore’s elder brother) married Jnadabhiram Barua, who is the son of Gunabhiram Barua (1837-1894)- the playwright of Ram Navamir Nat which is considered the first modern Assamese social play. This is also the first of the two translated plays of this slim volume Modern Assamese Drama. The translator explains her inclusion of this familial information in the line “The world is thus a small sphere and we are close to each other and not distanced”.

An amalgamation of cultures and languages has happened most organically in this country rich in its diversity and has defined its essential “Bhratiyattwa” or “Indianness” in a most profound and clear way. The purpose of the translation, therefore, is to bring close all that remain far with the barrier of language.

First published in a book form in 1870, the play Ram Navamir Nat tells the story of widow remarriage and the numerous social practices, prejudices that were threats to a psychologically sound living for both women and men of those times. The Hindoo Widows Remarriage Act passed on July 1856 legalised the remarriage of widows in all jurisdictions of India. Dating back to 1857, this play by Gunabhiram Baruah was an appeal to the people of Assam to wake up to the necessary social reform of widow remarriage in order to build a healthy societal structure where women would not be judged, rejected and exploited for their marital status. By that time, Bengal under one of the most able reformers, Pandit Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar had done away with the heinous practice of Sati Daha, where widows were sent to burn on the pyres of their deceased husbands. The play holds the mirror to a society infested with greedy moneylenders and self-proclaimed lawmakers who pounced upon those in the lower tiers of the economic ladder with brutally punitive ways.

The relevance of translating this play in the twenty first century lies in the fact that in India, while legally and constitutionally a person should be protected from the birth whichever might be his origin in terms of caste, gender, religion and economic status; in reality, we know the unjust discrepancies, ways to silence dissenting voices remain ingrained shamelessly in the fabric of the societies. Widowhood might not be the glaring social vice now but casteism, and robbing the economically poorer sections of people off their rights to a dignified living is still a truth we confront on a daily basis. Such plays could be the weapon for the fight against all that is socially unfair to the core.

In Navami’s narrative, a young widow meets Ram, falls in love with him and gets pregnant with his child. Both of them meet a tragic end by committing suicide, finding no support for their plight from the society they belong to.

A play becomes the true voice of the society in the different conversations that the characters break into. Shivakanta, the money lender comes to console Peloni who has lost her son-in-law and asks her to return his money. When she begs for some more time to do so and promises not to disappear before repaying, he reprimands her, saying “You damned woman! Aren’t you just a mere bond-servant! You do exhibit too much of a damn courage to speak thus” (2023: 23). It is as if the readers can learn what is unacceptable and insensitive behaviour from a human being. It is also a known fact that we need to revise this learning in all ages.

Mahajan, knowing of Nabami’s pregnancy orders the people to ward off Sivakanta’s homestead and if only they paid five hundred rupees would they receive a pardon. To this Xihuram says, “It is only if money is given that the sin will be forgiven. In every matter, money walks right into the courtroom (2023: 97).”

The reader cannot but think how little has changed in the past century for all who seek justice at the courts.

The second play of the volume Modern Assamese Drama published by Penprints India is Ebelar Nat written by Birinchi Kumar Barua (1908 to 1964). Written in 1955 by this versatile educationist who was also an adept folklorist, novelist, and historian, this play delves into the social milieu of modern Assam in the backdrop of the teagardens a few years after the Britishers left this country. In this play, Dhaiyyacharan Barua, the protagonist- a tea garden owner finds in the end, all those who he held close to his heart, his wife and three children, could not render the necessary support, the little care, concern one needs to survive the harsh world despite being showered with all the luxury, money could buy for them by him. The translator writes, “The play beautifully fits into the mould of the unity of time and action. It cannot be brushed off as just a period play. It is a social drama relevant to its times. The raw scathing deal of unconcern and disregard of marital couples and children for their parents has, in fact, mounted with modernity stepping in to kick aside not only the tradition and culture; but also, the deep bond that children had once shared with the parents. There are indeed summits, traumas and challenges in life. But the family bond of love and simple warmth defeats it all. The way the birds and beasts eagerly fly back to their nests and hideouts, hammer home the message for mankind.”

A fine commentary on people belonging to the higher strata of the society, this play reveals the selfish nature of those who live off another person’s money and generosity by virtue of being family.

When asked to donate a hefty sum of money for a social cause Madhuchanda says, “I shall try to speak to my husband and get him to contribute as heavy a sum as possible. After all I too have to think of my honour and respect as you’ll have chosen me as the Secretary of The Welcoming Committee. If I now act miserly when it comes to the donation, why will they honour me with such a post in the future (2023: 130).”

The vainness of some people in standing by social causes gets revealed in the lines mentioned above.

Clearly it is never about others, but most always about their petty gains and some kind of ‘rise’ in their status that so many people hanker for.

This play can be termed “sexist” in parts, at least by the modern standards. When Chanchal says, “For example, let’s say that a girl has her marriage settled with a youth, whom she happens to know very well. But when a new and better suitor appears in the family horizon, he is taken to be a better choice. Her parents therefore decide to get her married to the second suitor. In her excitement at settling down to a married life, she will soon forget her old suitor in no time (2023: 139).” Elsewhere he says, “Woman longs for comfort, luxury and rich husband (2023: 140).” In the conversation with his sister, Chanchal makes no effort to hide his patriarchal views of the world. It seems the plays are the mediums that can measure the progressive or regressive nature of the society and E belar Nat does a good job of it.

The reader will find striking similarities with the present socio-political milieu in the conversation between the two friends Lakhilochon and Dhaiyyacharan. Lakhilochan says, “They pressurise us by saying, do charitable here, help us there. When I approached them for a permit for the rice-mill, I was at a loss as to how many fund-raising schemes I had to offer money to. My money flowed out like the flooded waters (2023: 151).”

To this Dhaiyyacharan says, “My misfortune too is similar. I am in great fear as I am apprehending the Government arriving at any time at my doorstep, to snatch away the few acres of paddy field that belong to the tea garden. The lawyer Nikunj has advised me to offer a whole bag of ten thousand rupees, before any event. As it is, the garden is slipping out of my hands. How can I now offer ten thousand rupees and pose as a generous contributor (2023: 151).”

By this time, most of us know extortions come in the garb of demands for donations and the Government often instead of ensuring the mental well-being of the people, which adds to their misfortune. But while one can still accept and reason out the unfair ways of the Government because there is a palpable distance between them and us, and clearly they do little to for us to raise the bar of expectations from them; it is hard to accept the ideological differences with one’s own especially if you have raised them with lots of care and love and see no reciprocation from that end. Both the plays have their finger on the pulse of the protagonists- their problems in manoeuvring through the mostly hostile situations of their lives.

The plays come with explanatory notes from the translator that makes the reading easy and comprehensive. Barring a few typing errors, the book with a gorgeous cover page made by the translator herself, makes a lasting impression on the readers’ mind. Professor Upendranath Sharma, in his foreword, talks elaborately on the translators’ body of works and calls this book a laudable venture. For the readers it would be like exchanging views with people of the bygone times on their sinuous ways of living, only to realise that the journey comes with their own share of challenges in each century. But playwrights, authors and poets, we know, carry the mantle of letting us see the truth of human living with all its ignominies, imperfections, resilience and hope.

Also, read Suspected Poems Book Review by Shubha Sundar Ghosh published in The Antonym

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments