In some strange way, the apocalypse has always been the quintessential object of desire. All the major religions seem to be founded on an apocalyptic imagination, and even in our secular contemporary culture, the apocalypse looms large. In fact, we might even say that no other era of human history has the apocalypse been so mainstream. And here I am not speaking only of the real apocalypses that threaten us: environmental catastrophes, global pandemics, nuclear Armageddon, and so on. I am also speaking of the ubiquity of the apocalypse in mainstream cultural production. For example, all the movies and television shows that are part of the Marvel or DC cinematic universes have plots that essentially revolve around averting the apocalypse, which gradually intensifies from a global apocalypse in the first Avengers movie to a universal one in the second (and even a multiversal one in the movies and series that follow).

This ubiquity of the apocalypse in our collective cultural imagination (even if it appears in the form of that which must necessarily be avoided or averted) reveals the disavowed desire for the apocalypse. Such a desire is not just a desire for death and extinction. It must also be seen as a desire for redemption and emancipation. In fact, that is how the apocalypse has figured in the major religions of the world: annihilation and redemption. This is why, despite the apocalyptic tone of contemporary cultural production, we must say that it is still, on the whole, too optimistic. This claim of optimism must not be seen to be derived from the way the apocalypse is always averted but from the centrality of the event itself. In a way, we desire it because we believe that only an apocalypse can save us. This desire for the apocalypse reveals the apocalypse as desire— the desire to make a radical break with the way things are.

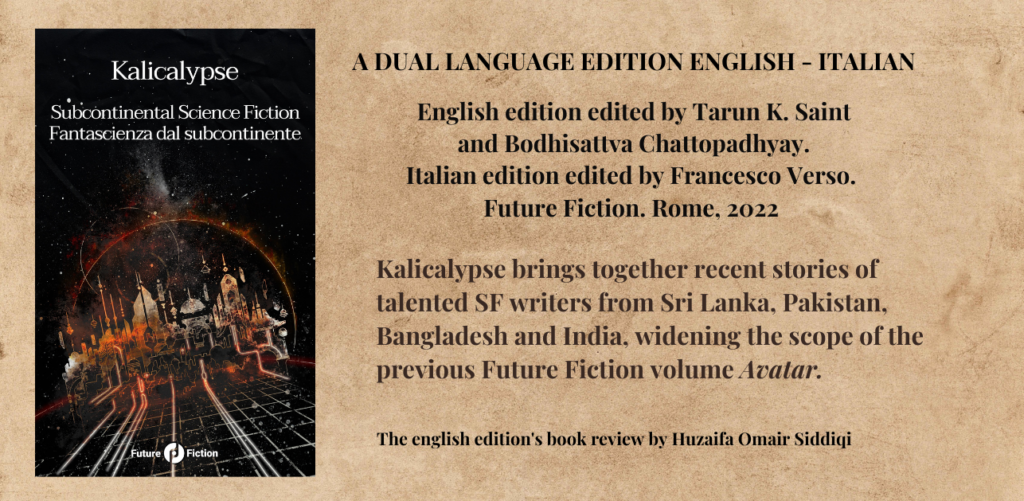

Kalicalypse: Subcontinental Science Fiction, a collection of ten short speculative science fiction stories edited by Tarun K. Saint and Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, has a sobering message: that even the apocalypse cannot save us. All the stories collected here deal with life after the apocalypse has happened. Yet rather than the event opening up emancipatory and redemptive possibilities, all that transpires is an intensification of contemporary inequalities and injustices.

Caste, religion, gender, and economic disparity: these are the four major fault lines that divide the Indian subcontinent. Kalicalypse includes stories by authors from India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. The majority of the stories were originally written in English while some have been translated. What is common to all of these stories is how they play with these four fault lines dividing our contemporary society and demonstrate how in some way or the other they will survive even the apocalypse itself. Shweta Taneja’s story The Daughter that Bleeds is based on an auction in a dystopian world where the wares being auctioned are young teenage girls called ‘bleeders’. In this world, a girl who begins to menstruate is a crucial commodity to be sold to the highest bidder; the entire economy and even the state are built around the protection and circulation of this commodity. In Indrapramit Das’s story Kali_Na the fundamental faultlines are caste, gender, and religion: in a world where Virtual Reality (Veeyar) has become ubiquitous, caste discrimination remains a defining feature. The gods themselves have become part of the veeyar universe and exist in their full glory in the virtual realm. However, the virtual goddess Devi 1.0 must still face insults and backlash from trolls over her skin color and her very existence until she finally goes on the rampage, transforming from Durga to Kali. Navin Weeraratne’s story The New Migrants is about the fringes of the empire where gene editing (‘gene bashing’) has become as simple as coding. But this dissemination of technology leads to despotic repression in a world devastated by climate change: colonialism redux. Trishna Basak’s The New Humans also embodies similar themes of a futuristic society having advanced technologically but not politically or socially in its development of the eternal recurrence of bureaucratic corruption.

In Md Zafar Iqbal’s The Almighty religion makes a strange return in the future, this time not among humans (or humanoids) but robots. Iqbal’s story is about how rationality is sometimes simply a way to justify religious dogma. The robots in his story remain emotionless droids, yet even then they replicate the same kind of religious persecution and conflict that haunts our contemporary societies. Iqbal’s story is the most comic of the collection, and the tale drawn out here is as satisfying a satire as any in contemporary science fiction.

Most of the stories in this collection seem to strike a note of pessimism if not despair. Yudhanjaya Wijeratne’s story also falls into this category, but The Art of Possible does more than just depict a world bereft of hope. In this story, Yasasmin, a professional ‘Policy’ maker, and her husband dream of writing the ‘Policy to End all Policies’, which finally takes shape, after the apocalypse has occurred as a book titled ‘The Complete System of Human Governance’. Though it is too late for the world of the story, perhaps the hint made at the potential existence of such a document seems to give us some hope.

Rupsa Dey’s story Anamnesis features characters who can hardly be called human anymore, inhabiting a world so strange that it takes several readings of the story to understand its dynamics. Sometimes, while going through the collection, I had the feeling that the form of the short story could be limiting to authors who had to world-build. The jargon is often bewildering and takes time to get used to, but perhaps that is the desired effect these writers want to evoke. Kehkashan Khalid’s story Steeling Minds is perhaps an exception to this in having a very relatable theme: social media. The future of social media, virtual reality, seems to bring with it no redemptive features and is in many ways much worse than it is today.

Haris A. Durrani’s story Tethered is a dystopian take on the future of space travel. It is about a future where there is so much space trash orbiting our planet that space travel becomes impossible and the only spaceships that exist are used to clean the trash circulating around us. But it is also a narrative take on the adventure story, gradually and intensely building up to a climax which is on the whole a bit underwhelming. Salik Shah’s The Architecture of Loss is a story that needs more than one reading and would not be recommended to the impatient reader. Shah seems to fuse two similar yet separate genres, speculative fiction, and magic realism, though the success of that endeavor is not absolutely convincing.

Science fiction is as much about the present as it is about the future, and the overall effect of this collection reflects the global pessimism that is so dominant today. It forces us to delink social and technological progress and most of the stories actively express a pessimism towards technology that differs from other collections of Asian science fiction published over the last five years. Yet it manages to do so along with highlighting how the struggle for change continues even in the most desperate times. If the apocalypse is (as the famous movie title goes) now, and not some unspecified time in the future, then the writers and editors of Kalicalypse seem to be telling us that we have to stop hoping that the apocalypse can save us. Neither a god nor an apocalypse: only we can save ourselves.

Read the interviews of Tarun K. Saint, the co-editor of the English edition, and Francesco Verso, the editor of the Italian edition here.

Also, read a Bengali non-fiction piece, written by the Bangladeshi writer, Hasan Azizul Huq, translated into English by Sukti Sarkar, and published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

For the month of September, The Antonym will be celebrating Translation Month to mark International Translation Day celebrated on 30th September. A number of competitions, giveaways, podcasts, and more have been lined up for the occasion. Please join The Antonym Global Translators’ Community for updates!

0 Comments