It perhaps does at least to some extent. It’s actually the world that we all have at some point in time envisioned what we inhabit to turn into. But since we failed to accept whatever came our way beyond the borders of what’s a prerequisite for us and molded it in accordance with our own limitations in a way succumbing to them, we have lost the chance to construct it.

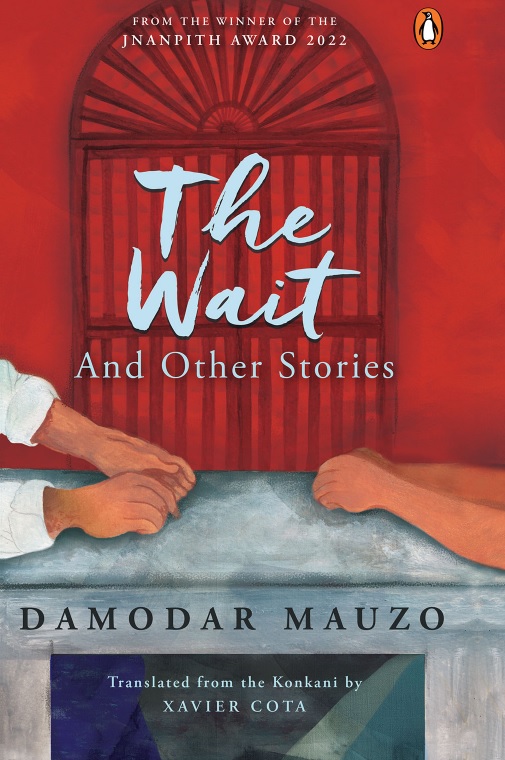

Mauzo’s stories, written originally in Konkani and translated into English by Xavier Cota, are mostly centered on the multireligious community of Goa, though not always limited within the geographical boundaries. Some of his stories deal with certain issues that we all acknowledge to be important but carefully avoid talking about when the need arises. The plot of each of the stories revolves around the ethics and the fallacies of human nature sometimes suggesting a standardization of the natural instincts of humans. Featuring characters from different social backgrounds, the stories in some way represent Mauzo’s own opinions on them and how he perceived them in both literary and non-literary contexts.

I shall not be writing the summaries of the stories; neither shall I be revealing the names of the characters featured in them; but I will definitely highlight certain aspects of the plots and show where they expand out of where and how they are placed and emerge to be universal.

The first story, The Wait, projects two people who apparently have normal lives, but have broken up their love relationship owing to some external familial interference. Such familial interference always takes a leaning towards patriarchy, and attacks who it assumes to be weaker, though there is no surety, a woman never represents such a hierarchical power structure contradicting the standpoint she is expected to have. Following the breakup, the man seems to have understood that his personal mood should not be a considerable factor in his professional sphere. He works, and in course of that oscillates between ethics and practicality. Towards the end of the story, the man emerges with his own sense of ethics which tells him what to choose between courage and supposed cowardice, and what comes to the fore at the end is how two people in a love relationship must know the time of their need in each other’s lives, and how such consciousness should actually keep them from turning disloyal. And that’s exactly the point where the wait becomes important for the relationship to mature, but not for the people’s individual ego.

The story, Yasin, Austin, Yatin, shows a cab driver who puts on the attire of religion to prove himself to be smart enough to fool people but is finally caught red-handed for something he never expected to happen. Apart from the fact that the story is about a man’s moral deficiency, what is as much important; if not more; is how religious biases change the traditional narratives and add different colors to them. The cab driver calls himself a Hindu when he has a Hindu passenger; a Muslim when he has a Muslim passenger; and a Christian when he has a Christian passenger and appropriates the local legends from such religious perspectives, modifies them, and narrates them to the passengers satisfying their fanaticism to earn more money. When, finally, the cab driver is to undergo a trial, we are left to think, if this is what we can expect to happen to everyone everywhere; irrespective of the biological form; who thinks religion to be the best to sponsor the personal benefits.

In the story, Burger, we see how society imposes religiosity on little children and how that gives birth to a fear that the institutionalized religions in turn accept. The fear keeps growing and takes a shape, and diminishes the confidence of the children leading them to self-curse. The story, however, ends on an optimistic note where Mauzo shows that reality stands much away from what is perceived as religion and that it’s pointless fearing what’s intangible.

I Haven’t Tied My Shoelace is a typical story that deals with two people’s love relationship since their college days culminating in marriage. A Konkani author prepares to go out to construct a story he is supposed to submit to the editor, but the unraveled shoelaces bring him to face multitudinous thoughts, one following the other, sometimes overlapping, with flashes from the past. Things start from the point he finds what he calls his wife to sound similar to what his former lover’s name was, and lead to his ruminating on how accidentally his wedding was fixed with his wife and not with some other one who was involved with them in a love triangle. This story refers to how elderly people interfere with their juniors’ personal affairs, throw vulgar expressions towards the women, manipulate the men with their ideological biases and subtly force them to doubt their own integrity towards others. In the end, on the one hand, when we find the characters to understand their lives to be much away from what they individually experienced in the past, we find, on the other, Mauzo to opine quite strongly on how natural it is for a woman to assert her partnership over the man she loves, and how what happened in the past should never have anything to do with what’s happening now beyond a particular point.

The story, Gentleman Thief, is one of the most unique of all the stories in the collection. This story shows the idiosyncrasies of a professor who sneaks into a house at night and introduces himself as the thief. What’s even more surprising in this story is how a thief is labeled as a thief more by the community he goes against than by what he does. I would rather leave it to the readers to explore this story more than reveal any more of it.

The next story, The Aesthete, has an intertextual reference to Gabriel García Márquez’s story, The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Erendira and Her Heartless Grandmother. Mauzo’s story talks about the married life of two people where all the man is interested in is how beautiful his wife looks. Just as the man wants every other object to be in perfect order in his house as well as in the hotels he puts up, he wants his wife’s skin and her appearance to remain ‘perfect’ so that he is never made to feel uncomfortable either at home or in public. This objectification of the woman’s body is what Mauzo highlights throughout this story by referring to García Márquez’s story where one can find the grandmother pimping his granddaughter to earn money. Mauzo’s story left me to wonder if the man’s constant craving for an appreciation for his choice of the lady he married thereby passively asserting his gender superiority is not way more gross than just a public commodification of her. I personally found this story to be extremely disturbing within the literary space but at the same time important outside of it, because this shows how Mauzo revealed one of the most objectionable instincts every man possesses.

As the Ice Melts is one particular story that definitely deserves special emphasis because this story shows how a person succeeds in keeping his humanity alive despite having to fight against the toughest odds. An army man, the major character keeps on practicing writing and chasing his dreams to be an author even during the Kargil War. He exhibits a different kind of empathy when he expresses, the people of his country for whom he fought include the family members of the ones fighting and that the families of the rival team are as important to be taken into consideration. The man finally leaves the army and follows his heart’s call, and after a long time, his humanity is acknowledged though through the expected tragic incident.

The following three stories, The Jalopy, Night Call, and I Was Waiting for You, delineate three different angles of man-woman relationships functional irrespective of the regional restrictions. The Jalopy talks about a man whose loyalty towards his wife makes him hesitate to speak about a girl he had loved earlier and was supposed to marry. The man’s wife comes to know of her husband’s helplessness for which the marriage didn’t materialize and keeps her reactions short unless she meets the lady accidentally and thanks her. Night Call on the contrary is a story about the temptations a married man faces, how he responds to them, and how the turns in the events take him back to his place. I Was Waiting for You is one particular story that shows the hypocrisies of human beings when it comes to their asserting their own moral values in public. In the story, a woman was gang-raped following which she started fighting back with faint moral support from her boyfriend. However, the boyfriend sensed, his image might be tarnished due to his involvement in his girlfriend’s accident and ran away. Though it seems, the story apparently portrays the whims of patriarchy, it’s the woman who turns triumphant in this moral war when we see, she has now become a successful lawyer and finally rejects a marriage proposal from her former boyfriend when they meet after quite a long time.

The Next, Balkrishna too deals with a topic like one of the two people in a married life resorting to infidelity considering the situation to be outwardly unacceptable. In the story, the woman becomes pregnant, and she is not sure about who the father is. Her fear of her child’s not being accepted by her husband is sidelined; thanks to Mauzo for choosing a different way to proceed with the plot; and her guilt, obtained through realizing her mistake, is manifested in the way she hides her relationship with her neighbor from her husband on the one hand and insists her husband change the name of the child on the other. The child’s name, Balkrishna, was significant for both his father and his mother, but the mother’s decision to change it shows her regret and that she wants that particular name to be given another child she supposes she will bear in her attempt to be absolved of her wrongdoing.

The last three stories, The Lover of Dreams, The Coward and It’s Not My Business are predictable, unlike the previously mentioned ones.

The Lover of Dreams must remind a reader of an immature infatuation he must have had with somebody at some point of time in his life, and how the vast difference in their socio-economic backgrounds never let ends meet, though he kept trying in spite of knowing such a venture would not bear any fruit.

The Coward is a story mainly about a tiatr group in Goa led by a man whose pride in his machismo is reflected primarily in his verbal exchanges with his wife and his child and with his teammates. The story, apart from describing in detail how a tiatr show is arranged, and how the team members work collectively to make it a success, shows a subtle difference between a father and a son often on the verge of turning fatal due to lack of negotiation.

The final story, It’s Not My Business, shows the descension of a common man who associates himself with the ruling political party of India and suffers internally the consequences of his compromises. He stands as the representative of all who commits to immorality knowingly and walks away safe from the negative effects of it despite knowing their avoidance of such issues might mean a disaster for others, perhaps their closest ones. Here again, we see the oscillation of a man between ethics and practicality, the latter, subjective, and how he tries to deal with his conscious knowledge of his escape.

Whether Damodar Mauzo’s stories reflect his own thoughts about society or not should not be a concern within the literary space, but, again, what’s to be considered important despite that is how his voice never moves from its standpoint nor falters even when he comments on certain harsh realities he doesn’t seem to want to exist in real life. Some of the stories that explicitly expand out of the plot and emerge as universal look more like they have evolved naturally from Mauzo’s thoughts and have thereafter been rendered spontaneously than they have been constructed consciously. The language Mauzo uses while even referring to the vulgar expressions shown by his characters is suggestive and is never too gross to face. The conclusions he reaches, though at times predictable, are never unjustified if their formation will have been investigated. But above all, to many, as I said earlier, this book will reveal a world less known than usual, and that makes it worth reading as much as its literary richness does, if not more.

Also, read an Italian fiction, self-translated by Tiziana Vigni, and published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments