Supranowicz, who grew up in eastern United States’ Appalachia as a descendant of Irish and Eastern European immigrants, has been a digital artist for around a decade. His work has been or will soon be published in Fish Food, Streetlight, Another Chicago Magazine, The Door Is a Jar, The Phoenix, and The Harvard Advocate.

The Antonym caught up with digital painter and poet Edward Supranowicz, our Artist of the Month, to find out more about his creative pursuits.

Atrayee: How did you become a digital painter? When did it start? Did you go to school to learn the ropes, or did you teach yourself?

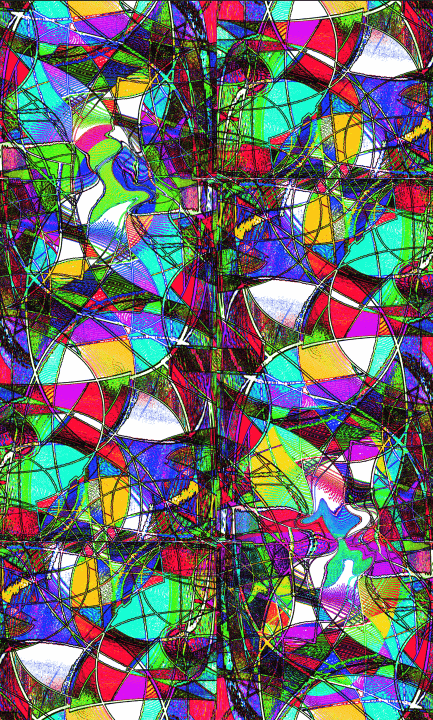

Edward: When the factory I was working in closed down about fifteen years ago, I went back to school to pursue another degree, figuring it would probably end up being as useless as the others I have. But having bought into the education myth and most of the American ones, I gave college a try again with a degree in education. It wasn’t long before I was completely stultified and looking for a way to break the monotony. I saw a course listing for “art on computers” and decided to give it a try. It was frustrating at first trying to approximate my style of drawing and painting by moving a mouse. It was not as direct and immediate, but after several years of trial and error I was able to use this somewhat indirect process to create artwork that looked and felt direct and natural.

Atrayee: How has the journey been so far? Does this relatively new art form give you an edge in this day and age? If so, how?

Edward: I am not rich and am often one step away from homelessness. To put on a show in a physical, traditional gallery might cost me several thousand dollars for printing and frames, not to mention lugging stuff back and forth. But with digital prints I can do an online exhibit from my own apartment with little cost and without traveling. Plus, digital prints allow me to share an image with more than one person and can also be a digital diary of the body of one’s work.

Atrayee: That sounds quite realistic. Please tell us about your subject. Where do you seek inspiration for your work? Has growing up in Appalachia influenced your work in any way?

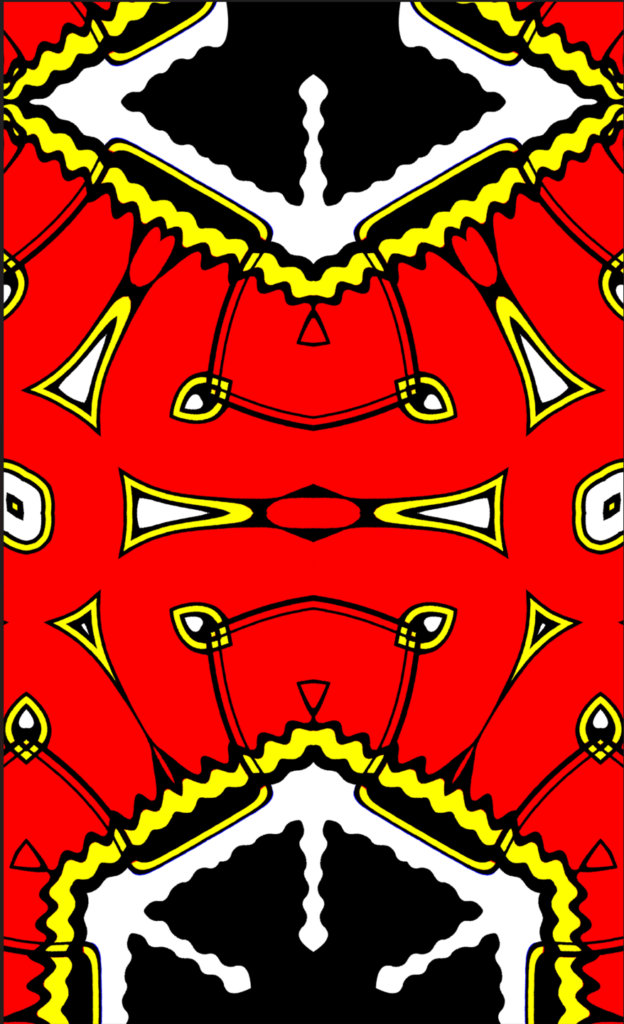

Edward: Anything and everything can influence or inspire us or do just the exact opposite. We live, we breathe, we act, and maybe we are conscious, but it is like the iceberg analogy where only a small portion is above water, and we try to see the unseen, which can be a motivator in its own right.

Atrayee: How do you approach your work? What method do you follow?

Edward: I sketched and painted with traditional methods and materials before I did digital work. So, I do carry over some of those approaches in digital work—lay out backgrounds, do gesture drawings, use line and color, all of which will always be part of painting, even when and if we get to the point where we can paint directly from our minds into other minds.

Atrayee: From one mind to another. There’s an idea! So, what is your go-to software and hardware? Do you have any favorites?

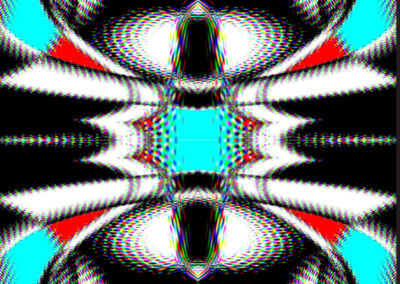

Edward: I have used different drawing and painting programs but have focused on GIMP for the last five or six years since it is open source. The last Photoshop I had on disc went down with a worn-out computer, and now one pays forever for the cloud version of Photoshop, and not everyone can afford the expense. I use a USD 300 HP desktop I bought with the last round of stimulus money. As long as your computer works and can hold the programs you want to use, it does not matter if it is new or old, cheap, or expensive.

Atrayee: How important do you think technical knowledge is for a digital painter? Do you have any advice for painters out there struggling to zero in on the right hardware?

Edward: I think general knowledge of painting and its history is more important than technical knowledge of equipment. See what you can do on the cheapest, simplest of machines and budgets. You might be surprised that overcoming one’s own imposed limitations sometimes stretch the capacity of the machines or materials one is working with.

Atrayee: That, again, is extremely realistic. What, according to you, are the biggest advantages as well as challenges of digital painting?

Edward: For me, one of the biggest advantages of digital paintings is being able to go back and forth, try different combinations of color and line without wasting all of one’s paper or canvas. Plus, digital paint does dry a lot quicker than oils or acrylics. Sometimes not being able to hold a brush or squeeze a tube of paint, the tactile and sensory part of creating, seems to be lost with digital work. But then again, there are a lot of toxic chemicals involved in making art, which I do not miss by doing digital work.

Atrayee: What does the market look like to you?

Edward: I do not understand markets for art any better than I understand why football players get twenty million dollars a year for playing a children’s game. But art has never been valued as much as it should be. In America, maybe we can blame the Puritans for that. I would like to think that art is spiritual or should be, but people have trouble being transcendent—the old spirit is willing, but the body is weak.

Atrayee: Each of your painting comes with a unique title. Is that the poet in you talking? Tell us about your experiences as a poet. How does poetry, if at all, help your art?

Edward: Edward: I have had about 700+ poems published, but not so many the last few years, so maybe I am putting the poetic impulse into the titles of my work. Maybe I am giving a hint of what I intended by the title, or maybe it is meant to tease and provoke, or just to ask if this makes sense, and if so, why, or why not.

0 Comments