Atrayee: You call yourself “a scientist and a student of poetry”; you are a photographer too. How do these worlds converge?

Deb: I have wondered about this question myself for some time. The more I think about it the more I feel that they are indeed integral parts of me that respond to each other all the time. They are born when curiosity and an urge to discover something new somehow converge at a point.

As scientists, we receive many years of rigorous training. Most of the things we envision do not work out as expected, but a few of them do spark a new light. So ultimately, it boils down to what we do with that training. Am I able to continue to struggle, and come up with new ideas? This is a question that a scientist faces all the time. So, every few years, we have to be reborn, which, in fact, makes this journey so interesting. When it comes to art, I feel the same nature of joy of being reborn every day. It is like looking at the same thing, though a bit differently every day.

However, calling myself a poet is too heavy a title to carry. I don’t have the same level of preparation, but I like being a life-long student—being on a journey to discover myself and my surroundings.

Photography is a more vivid form of artistry that often helps to express myself when words fall short.

Atrayee: You are a physicist specializing in nanoscopic materials that interact with light—photons in particular. Does your understanding of physics contribute significantly to the manner in which you look at photography? How does it affect the way you address light and color?

Deb: It is interesting how I ended up here. As a graduate student I spent every day of the week in a dark room looking at nanoscopic objects, like nanowires and nanotubes. These are materials at the lower bound of solids, nearly hundred thousand times thinner than human hair. I was interested in learning how their size, shape and atomic arrangements dictate their physical properties. It’s the multimillion dollar electron microscope that sowed my interest in photography, and a habit of looking for things deep inside that are otherwise hard to notice.

So, when I purchased a decent camera for the first time, I ordered the best macro lens I could find. I spent some time photographing microscopic objects like grains in bread, eye of an insect, and things like that. But later, I started linking abstract ideas with them, along with poetry. Thanks to Antonym’s Montage section, I have started to explore this union of words and pixels—it is the perfect place for this rather unconventional art-form.

Atrayee: Thank you. That sounds intriguing! Now, can you please tell us about your process?

Deb: I usually have a vision of what I want to capture with a camera, and my understanding of light-matter interaction certainly helps to a certain extent. But most of the time when I arrive at a scenic place, nothing seems to work according to my expectations, which is when the process of rebirth begins. At times, unexpected images, and ideas spark from there.

In case of writing, sometimes I see a snapshot at first—sometimes a single word comes to mind, following which the rest of the imagery begins to emerge.

Atrayee: What are you interested in photographing? Are you essentially an outdoor/nature photographer?

Deb: I am not sure if I can call myself a specific type of photographer, but I am mainly interested in capturing something new, something that has not been captured before, in things.

Atrayee: Why did you create Life in a Canyon? Can you share your experience of working on the series?

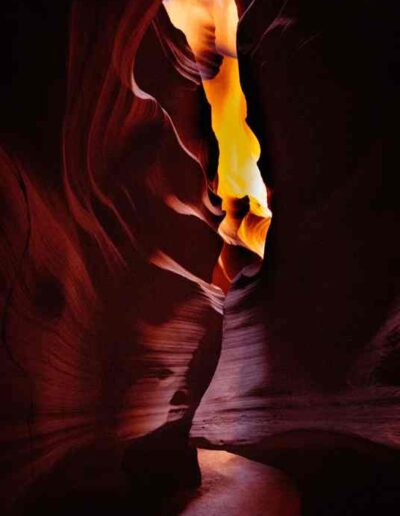

Deb: Antelope Canyon is a photographer’s paradise. It is located on the Arizona-Utah border, near a small town called Page. Millions of photographs are taken to this 100-yard-long slot canyon every year, yet something new can be discovered every time.

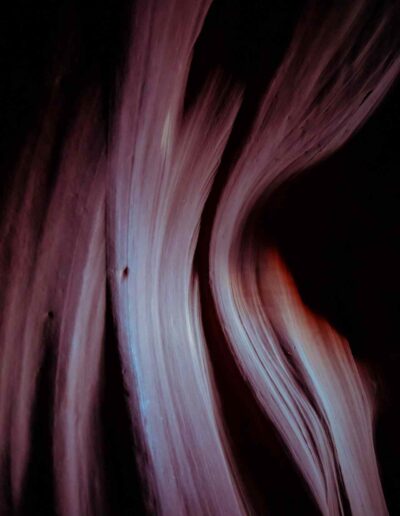

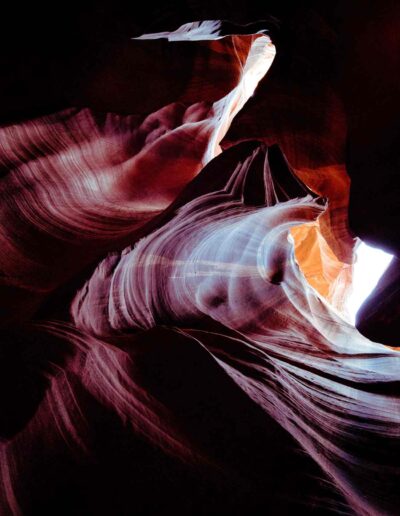

The canyon was formed over thousands of years of flash flooding of the intermittent creek running through it, wearing away the Navajo sandstone rock-face before emptying into the Colorado River and now into Lake Powell nearby. During long periods of drought, windblown sand would polish the narrow slot walls into a striated, swirling finish.

My vision to take these photographs was to depict the fact that it is not a place of ancient remains; rather a lively neighborhood where geophysical phenomenon is on the move every second. There is an ever-changing play of light upon its walls, and the sandfalls that cascade into the depths of the slot canyon. The sunlight brings life to the curvature that were once created by waves. To me, these are the signature of the omnipresent fluidity that are curved onto the walls. As humans, we should recognize and respect the fact that we live in a wild world where life is intermittent, and where change is the only constant. In fact, I can feel it vividly on this chilly winter morning.

Atrayee: Well, you gave us a lot to chew on. Now let me ask you this—while Life in a Canyon is in color, a lot of your works are in black and white. How do you arrive at the decision? Do you think black and white photographs are serious in a way colored ones can never be?

Deb: Absolutely! I would pick black and white photos any day. They always communicate a better story—if a photographer can manage to pull it off. This is a big “if” though. On the other hand, it’s also challenging to use colors in photographs to tell a story. They usually create an unwanted distraction. In this case, however, colors are part of the story; at least the story I wanted to tell.

Antelope Canyon was formed by aeolian deposits—sediments deposited by the activity of wind. Such deposits at Antelope Canyon began around 191 million to 174 million years ago during the Jurassic Period. Iron oxide deposits were mixed with windblown sand, resulting in layer after layer of varying shades of orange and red. The guide told me the iron oxide came from far off places carried by wind and water, that were then deposited onto these rocks. So, the colors only embolden the story of motion that I wanted to tell.

Atrayee: You have created several works using drones in the past. Do you consider technology to be a primary aspect of your art? What knowledge of technology do you believe is absolutely crucial for a photographer?

Deb: A few years ago, I got interested in aerial photography mainly because we usually don’t get to see this dimension. This is good tool for showing more of the places we already know, feel and touch. This was the only motivation, and with the massive technological progress of drones, possibilities are limitless. However, drones probably are not making a good impression these days, and more and more places are banning them, including national and state parks. That makes me sad.

I am interested in any technology that can offer a bit more than the usual fare. Yes, I think understating your gear is necessary for producing the best results.

Atrayee: What is it that you want to say through your photographs?

Deb: I want to tell a story through my photographs that can be told in no other way, or by no one else.

0 Comments