The Italian novels of Algerian-born writer Amara Lakhous take the contemporary immigrant experience as a lens through which to interpret the world. Lakhous’ novels apply a light touch to the big questions: identity, language, relationships. For Lakhous, the displacement experienced by the immigrant, as well as by many people within their own countries, speaks directly to the heart of all literature: our relationship to the “Other.” This sense of estrangement, as well as the search for human connection, is evident in all Lakhous’ works, along with the array of misunderstandings, both comic and tragic, that often arise from cross-cultural encounters.

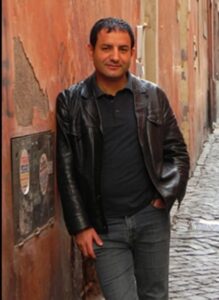

Born in Algeria in 1970, Lakhous attended an Arabic school and studied French before working as a radio journalist. After fleeing Algeria’s repressive political and cultural climate for Rome in 1995, he received a second degree in cultural anthropology from the University La Sapienza. Fueled by his passion for Italian culture — especially the cinema of commedia italiana — Lakhous began writing in his adopted language, seeking to create a new style that could “Arabicize” Italian and “Italianize” Arabic.

The resulting novels, all set in Italy, lend the humor of commedia italiana to Lakhous’ explorations of language, identity, and displacement, framing these questions within the structure of the giallo, or crime novel. Scontro di civiltà per un ascensore a Piazza Vittorio (published in 2006 and translated into English in 2008 as Clash of Civilizations Over an Elevator in Piazza Vittorio), takes a murder in a Roman apartment complex as a pretext to recount the diverse cultural perspectives of the victim’s neighbors. Divorzio all’islamica a viale Marconi (published in 2010 and translated into English in 2012 as Divorce Islamic Style), tells the story of Christian Mazzari; an Arabic-speaking Sicilian who goes undercover to infiltrate a terrorist group in Rome, he is soon distracted by the wife of one of his targets. Contesa per un maialino italianissimo a San Salvario (published in 2013 and translated into English as Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet, 2014) takes place just as Romania is preparing to enter the European Union; the novel explores a rumored war between Albanian and Romanian gangs in Turin while at the same time exposing the absurdities of the contemporary political and cultural landscape. Currently, Lakhous is at work on a new novel, again set in Turin.

Lakhous was the recipient of the prestigious Premio Flaiano in 2006, as well as Algeria’s Prix des libraires in 2008. He spoke with me from his home in Paris.

Meredith K. Ray: I’d like to begin with a general question. You’re an Algerian-born writer who chooses to write in Italian. What can you tell us about your journey from Algeria to Italy (you lived in Rome for sixteen years), and then to France, where you are living now?

Amara Lakhous: Well, let’s put it this way. I realize that in some ways I’m an unusual case, because so many writers — not just Algerian ones, but North African writers (Moroccan, Tunisian) — have had a relationship with France because of colonization. So they have a very strong relationship to France. If they have to go abroad, they go to France. If they have to write in a language that isn’t their native language, or their country’s official language, they write in French.

I decided, on the other hand, to make a completely different choice: to go to Italy and to write in Italian. And there were several reasons for this — first of all, I left Algeria at a very difficult time, in 1995, when I was working as a radio journalist. And, like many journalists and young writers, I had problems . . . and it was necessary for me to leave. I was able to get a visa for Italy because a dear friend of mine, an anthropologist, had invited me there and I was able to get a visa that that allowed me to leave Algeria. But this obviously does not explain why I stayed in Italy, instead of going on to France. But I am a little crazy, and I said to myself, it would be good to do something original.

I’ve always thought of art, of writing, as an act of creativity and originality. So I said to myself: I could go to France, where I already speak the language. I could write in French, like so many others have done — others who, quite honestly, have more opportunity and a greater ability than I do, because I did not attend a Francophone school. I went to an Arabic school. Even though I spoke some French, which was taught in grade school, at a certain point they decided to Arabicize everything. So everything — math, physics, history — was taught in Arabic. Obviously, this took away from the weight of French in Algeria. I think it was more a demagogical act than a cultural one . . . but that’s another story.

Anyway, I went to Italy and I thought it would be good to do something original, even though when I first arrived in 1995 I didn’t have this idea of writing in Italian yet. When I got to Italy my first goal was to learn to speak Italian — to learn the Italian language and to learn the Italian culture and society. Because — and this is another fundamental part of it — even before I went to Italy, I had a deep passion and a deep admiration for Italy’s culture, especially cinema. I had discovered it as an adolescent, when I used to go to a cinema in Algiers that showed the films of the great directors, and I was crazy about it. I used to go twice a week and I realized immediately that Italian cinema is something truly exceptional — especially Fellini. And when I got to Italy, one of my motivations in learning Italian — you always need something to motivate you to learn a language — it’s crazy, but really it was this: to be able to see Italian films that hadn’t been dubbed, to hear someone like [Vittorio] Gassman or Alberto Sordi acting in their own voice and language. And that was a great pleasure. I remember I soliti ignoti (Big Deal on Madonna Street, 1958), a film by [Mario] Monicelli with Gassman and [Marcello] Mastroianni. In the version I had seen in Algeria, which was dubbed in French, Gassman spoke a normal kind of French. But in the Italian, he stutters and stammers . . . it’s fantastic. All that gets lost in dubbing — the character gets lost. So, I had the chance to recover Gassman, to save him!

I had always known that Italian culture is an extraordinary thing. I knew this and had seen evidence of it and wanted to learn about it in more depth — that’s the first thing. The second thing was to follow a new path. I already spoke French, but I didn’t know Italian, so adding another language, learning about another society, one that had immediately transfixed me. I’m speaking of Rome, where I lived for sixteen years, an extraordinary city and the setting for two of my novels.

These are some of my motives for the decision to go to Italy, to study Italian, to stay in Italy, to become in some sense a citizen of Italian language — a citizen of Italian culture. I am an Italian citizen, in the sense that since 2008 I have had an Italian passport. But what I like most is this linguistic and cultural citizenship that I really worked hard for.

In any case, after that, the decision to write in Italian came about. Because as a writer, I was born in Algeria, in Arabic. I wrote my first novel in Algeria in 1993: Scontro di civiltà in un ascensore di Piazza San Vittorio. I wrote it in Arabic, and then I re-wrote it in Italian. So little by little, this maturity, this intimacy with Italian, led me to start writing in Italian. And now, I find myself here in Paris, writing the first draft of my next novel, in Italian. Me — an Algerian, a Berber — I’m here in Paris. I often go to libraries — they have beautiful libraries to work in. In fact, I say to my wife, “I’m going to the office,” and I go the library. And I sit there, and I think: someone who sees me — I’m Algerian, I’m a Berber, I’m in Paris, and I’m writing in Italian. Someone sitting next to me . . . they would never guess where I’m from.

This choice to write in Italian actually happened later, it didn’t happen right at the start.

Meredith K. Ray: This brings up something I wanted to ask you about, which is exactly that — the problem of language in your novels. It’s something a reader notes immediately, because language has such fundamental importance for your characters’ sense of identity and belonging. There’s a wonderful quote in Contesa per un maialino italianissimo a San Salvario (Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet) that reads:

“. . . non c’è una radice più forte della lingua . . . Ogni persona che lascia la propria terra è come un albero trapiantato altrove, guai a privarlo delle proprie radici.”

(“There’s no stronger root than language . . . Anyone who leaves his country is like a tree that has been transplanted somewhere else. No one had better try to deprive him of his roots.”)

Can you talk a bit more about the process of writing first in Arabic, then in Italian?

Amara Lakhous: I wrote the first version of Divorzio all’Islamica a viale Marconi (Divorce Islamic Style), which was published in 2010, in Italian (I work on multiple versions — for example, Clash of Civilizations . . . had about twenty versions). When I finished — as you know, in Arabic you write from right to left — I divided the file and made two tables: Italian text on the left and Arabic text on the right. I have a multi-language keyboard, so I can go from one language to the other. And I would look at the Italian text, and write in Arabic, and if I found something that seemed more convincing as an image in Italian, I would change it. So the two texts were born together, and published within a month of one another: the Arabic text was published in August and the Italian text in September. They’re twins.

Meredith K. Ray: That is really interesting. It seems like a unique way to work.

Amara Lakhous: It’s an unusual case . . . I don’t think anyone else has done the same thing. You literary critics will have to confirm that. There are writers . . . I’m thinking of Kundera, and others who have written in several languages . . . but something like this — I don’t think so.

Meredith K. Ray: No, maybe not. Italo Svevo comes to mind, since he had so many linguistic influences and liked to play with question of identity and its expression in language, but this idea of actually creating the two versions at the same time is unusual.

Amara Lakhous: They were born together. Up to the very end, I would change things, add things, I really did a comparison, and these texts were — I don’t know how to say it — they were loved, they were improved, and they were published with two different titles, two different covers.

Meredith K. Ray: What was the Arabic title?

Amara Lakhous: Little Cairo.

Meredith K. Ray: For the neighborhood in which the novel is set (in Rome).

Amara Lakhous: Yes.

Meredith K. Ray: Would you say that they are the same novel, then? What impact does the language you write in have on the book itself?

Amara Lakhous: This work really calls into question the whole concept of translation, in the sense that I am not a translator. I’m the author, and so the author can do as he likes. The translator can’t add or cut out characters, for example, or take out sections and add others, or add new characters, or change their names. The title, maybe — to find a better title — but really, what I do, more than translate [traducere], is I betray [tradire]. I betray the original text. I add some things, I take some things out. So it’s a creative act, an act of re-writing, not translation. So in the end, they are twin texts with the same mother, the same father — but maybe one is male and one female, one is tall, one is short — they aren’t identical. They’re not identical twins.

Meredith K. Ray: In fact, I wanted to ask you about the difference between seeing your books translated, and re-writing them yourself. I know your last novel is about to be published in English. How was it — after all that work you did, linguistically, knowing how important language is, how much creativity and flexibility there is in language — to entrust your book to a translator?

Amara Lakhous: I made the choice to work in two languages, Arabic and Italian, and I made it my goal to “Arabicize” the Italian, and to “Italianize” the Arabic. That is, to bring Arabic into Italian — and really, not just Arabic, because my origins are Berber, which has a very rich language, my mother-tongue — so I put some Italian into my language. And French too, really. And when I write in Arabic, I put in my new language, which is Italian — so I Arabicize Italian and Italianize Arabic. My Arabic style is very unusual — many critics and reviewers have noticed it.

Meredith K. Ray: Really, you’re creating a new language.

Amara Lakhous: I hope so. I’m following this path, and I hope it will lead somewhere. It’s already having an effect in the United States, where there’s a lot of interest, which is a great pleasure. It’s an unusual case. There aren’t really Arabic writers writing novels. I have friends who are writing short stories. But a writer who writes in two languages, like me, with a constant, clear literary program — maybe after me, there will be more.

Meredith K. Ray: What was it like to entrust your work to another person? Are you happy with the translation?

Amara Lakhous: Yes, of course. The interesting thing is that my novels have been translated in other languages, but only from the Italian versions. None from the Arabic. There’s only one case — because there’s a young man doing a doctoral thesis who wants to translate Clash of Civilizations into Berber. Because I speak Berber, but I don’t write it. Really, Berber is a language you speak, but you don’t write — there are various reasons for this. Obviously, there’s the political problem: because after the Algerian independence in ’62, we had the misfortune to have a stupid nationalism, and nationalism bases itself on having a single nature, a single religion, a single country — a dictatorship, really. It was forbidden to teach Berber in school. I speak it perfectly, but I don’t write it.

Meredith K. Ray: Is there a Berber literary tradition?

Amara Lakhous: Only recently. A few people have started to write in Berber. The first novels came out three, four, five years ago. So I chose to work in Italian, but there are other languages — French, German, English — obviously I feel closer to French, and they ask me why I don’t write in French, too. And I answer that I’m already a linguistic polygamist, writing in two languages. It’s complicated to add a third one. Complicated in the sense that — sure, I could add it to the list, but I don’t want to waste any time. Writing in French . . . I don’t know. Maybe English some day, I could add English. So in French, I have the possibility . . . My translator, Elise Gruau, is really great. Right now she’s finishing Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet, it will come out in a few months. When she finishes, she gives it to me to read. I read it like a reader. I tell her my observations, if she has a question, she can always ask me. My English translator, Ann Goldstein, who is in New York, sometimes asks me a few things, sometimes nothing. Dispute over a Very Italian Piglet, she did all on her own. I have a lot of faith in her. The Japanese translation too, and the Spanish. Let’s just say, I’m really happy about it, because through translation I can reach more readers.

Meredith K. Ray: While you were talking, I was thinking that a scholar would really need to read the versions in Arabic as well. The Italian version is only half the story, so to speak.

Amara Lakhous: There’s only a few who can do it. This Moroccan student is doing that exact thing. Comparing them — something interesting will come of it.

Meredith K. Ray: Let’s go back a minute to talk more generally about the major theme at the heart of all your novels: immigration. It’s clear that your own experience emigrating from Algeria had an effect on you and on your writing. Your novels are populated by immigrants to Italy from North Africa, but also by Italians (particularly southern Italians) who are like immigrants in their own country — they have to contend with similar kinds of obstacles and experiences. In some cases, like in Divorce Islamic Style, these two varieties of immigrant experience converge, as in the character of Christian. Can you talk about the centrality of this experience for you as a novelist, as well as the sense of — well, almost a kind of brotherhood — between Arab and Italian “immigrants” in Italy?

Amara Lakhous: Thank you for the question, because it’s central. But for me, immigration is a way — a very, very important way — to read and interpret reality: the reality of the world, the reality of Italy. And here we have to distinguish between immigration as a sociological experience and immigration as a literary experience. What do I mean? There’s a whole vein of criticism that reads — not just in my novels, but in those of other who aren’t of Italian origin, but emigrated to Italy, like me — they read them in a sociological way. So they examine themes like racism, nostalgia, etc., and I would say that’s an interesting approach. However, what I try to place the most value on is not the sociological experience, but the literary experience, because if we look in more depth at the big themes of literature and history, the relationship to the Other is one of the most important themes. A love story, Romeo and Juliet, isn’t [a love story,] it’s a story about the Other. War and Peace — the theme of war is the relationship with the Other. And so, through immigration, I am able to tell the story of the relationship with the Other. Two people who meet, two cultures that meet, two religions that meet — how can they know each other? Why do they reject one another at some point?

You can see that in my novels there have been various steps along this path. Because Clash of Civilizations tells the story of a Roman neighborhood, Piazza Vittorio, where there are immigrants and also southern Italians. This choice did not happen by chance. There’s one who comes from Milan, professor Marini, and the Neapolitan concierge. That was a great idea, because in that novel, you can see that Italian society is already a multicultural society, even without counting the immigrants. If we leave out the immigrants for a moment, and look at the Italians themselves — you’ll see it’s a multicultural society. In fact, when people say that Italy is becoming a multicultural society thanks to the arrival of immigrants, I say: No. What country are you living in?

This is the point I started from, until getting to Divorce Islamic Style, where I bring in Italian immigration in Tunisia (in the character of Christian, who is born in Tunisia), the relationship between Sicily and Tunisia. And then I came to Dispute over a Very Italian Piglet, where I ended up somewhere I didn’t expect. I meant to tell the story of immigrants in Turin, and what do I end up doing? I tell the story of the immigration of southern Italians (who relocate to the north of Italy), and I end up in Romania. In the new novel, I take yet another step forward, because the new novel is set in 2008, again in Turin, with the same main character, and it talks about the Roma — the Gypsies. And what do I do? I end up finding out that the Roma came to Italy in the Middle Ages — the Middle Ages! So they are more Italian than many Italians!

I try to work on Italian memory. The key is immigration, but not “non-European Community immigration.” I think of the five million immigrants living in Italy today, whether they are Italian citizens, residents, or whatever. Through this presence, of today’s immigrants, I try to open a discussion of southern Italian immigration, which is a shameful thing, forgotten. They were Italians — white, Catholic — and they were discriminated against. I lived in Turin for two years — I went to Turin in order to write this novel, to create the main character, the one I’m using now, I don’t know if I’ll use him again in the future — but it was a way to talk about immigration in Italy from within Italy and from outside Italy. And that was my goal . . . immigration as a key, not just sociologically or anthropologically, but in literary terms. To tell the story of the relationship to the Other.

And in this literary experience, language is central. If I Arabicize Italian, and use all my own experience, I work on Italian dialects, too. In the kind of criticism that looks only at themes — racism, discrimination, etc. — and ignores the question of language, this is something that is really lacking. We need scholars and critics who study the works of writers like me, writers who come from other cultures and other languages — they absolutely must give more attention to language. Because literature is language. Literature is style. It’s not just content, because we can find content everywhere. There are sociologists and anthropologists who can do a great job of describing Italy. They have data, theories, studies, statistics. But a writer arrives at it through language and describes the society that is emerging through language.

Meredith K. Ray: I also wanted to talk for a minute about the fact that all your novels are, in some sense, constructed as mysteries or detective stories. There is always a crime — or if not a crime, a question — at their heart. And your novels are also comic, even though they deal with important problems. There is a really nice mix of the comic and the serious. You have spoken about wanting to create a giallo alla commedia nera, a “comic crime novel” or “a black humor” crime novel. Could you talk about your philosophy with respect to the crime novel and the place of humor within a form that is, in many senses, very fixed in its conventions? How do these things fit together, and why do you continue to utilize this structure?

Amara Lakhous: Alongside language, this is another important part of my literary project. It was always my idea to mix two genres: the commedia (comedy) and the giallo (the crime novel). Obviously, commedia italiana derives from cinema — a big influence for me — and my novel Divorce Islamic Style (or Clash of Civilizations and Dispute over a Very Italian Piglet) is based on that. It’s a genre that hasn’t had much impact on literature. It has a lot of success in cinema in the 1950s and 1960s, then it’s done by the 1970s, creatively speaking. But there’s no corresponding literary school to speak of. This was something I wanted to change: to move the commedia italiana from film to literature. Because I think it’s possible — I say it in Clash of Civilizations, too, in the discussion between Amedeo and the young Dutch character, when they talk about Neorealism and commedia italiana. Really, commedia italianacomes from Neorealism — Neorealism is the mother. It tells the story of reality. But commedia italiana added this new element: to tell the story of reality but without this ideology. I’m thinking for example about the films of Dino Risi, like Una vita difficile (A Difficult Life, 1961), with Alberto Sordi, where you’re telling the story of workers, laborers, etc., and instead of using ideology, the party, the union, you tell a story with humor, with comedy, with leggerezza (lightness) — that’s a key word, one of [Italo] Calvino’s six categories (in Lezioni americane [Six Memos For the Next Millennium], 1988). I think commedia italiana is capable of telling not only the story of Algerian society but also Italian society. I’ll explain why.

In Algeria, I studied philosophy after high school for a reason: in order to have rational instruments to help me understand my society. I was born in an Algerian society — Berber, Arabic — and as I grew up, I realized that my society was full of contradictions. Full of contradictions. So I thought, only philosophy — the art of thinking, reflecting, etc. — can offer a possibility of understanding this society. So what happened? I studied for four years, and after four years I had a crisis because I realized that everything I had studied had no use whatsoever. Why? Because my society was an irrational society. Philosophy couldn’t explain it. When I came to Italy I found the same thing, because Italian society is full of contradictions.

Now, I hate to make anyone uncomfortable but . . . come on. [Former prime minister Silvio] Berlusconi — we’re allowed to make him uncomfortable! A phenomenon that cannot be explained rationally. A person who owns half the media, and the government owns the other half . . . ! I remember when he won in 2001, he was invited to talk with [Bruno] Vespa, a great journalist who has this political talk show Porta a Porta (actually, I use him in Dispute over a Very Italian Piglet [as a model] for Finestra sul cortile — it’s him). And Berlusconi shows up and Vespa asks him about conflict of interest: “You own television, banks, a soccer team.” [Vespa] said, “When the Consiglio di Ministri [Council of Ministers] decides to vote on these questions, which affect your interests, regulations, and so forth, what will you do?” You know what [Berlusconi] answered? He said, “We have an answer for that. When the Council of Ministers decide to talk about my affairs, I will resign from the Council of Ministers.” It’s a great answer! It’s extraordinary. He’s a comic personality of great effect.

In the new book I also begin with an event that really happened, that can’t be understood rationally. Only comedy can explain it. Giallo [crime writing] is a genre that has always fascinated me, because it manages to combine a million other genres. I don’t like passive literature, writers who recount their love stories, their disappointments. I say, a reader spends the money to buy your book — they go and buy your book, out of thousands — they spend all that time reading it, and you, the writer, what do you do? You ruin their day? There are certain books where you want to say, just go to a therapist and figure out your problem! I don’t like it.

For me, literature is a space for enjoying yourself. Leggerezza can also make you reflect. You can be delicate, sensitive. I try to remember this in using the giallo, which allows you to enter a dialogue with the reader. Although in this, I belong more to the school of [Leonardo] Sciascia than Agatha Christie or other crime writers. Because in Sciasicia’s novels, the criminal is never an individual, whereas in the classic crime novel, there’s an individual, an assassin. That’s the first thing. The second thing is that, in a classic crime novel, the criminal is defeated at the end, or killed. That doesn’t happen in Sciascia’s novels. There’s no single guilty person at the end. In my novels, I try not to give too much importance to who is guilty. What I mean is I think that the guilty party is always collective, not individual. In Clash of Civilizations, the main question isn’t who killed “The Gladiator,” but instead to tell stories about people’s lives.

Meredith K. Ray: In your use of the comic to recount things that are utterly incomprehensible, the absurdities of society, I also wonder if there is a link to [Luigi] Pirandello and his idea of the pazzo, the madman, as the only person able to really see society for what it is?

Amara Lakhous: Exactly. I mentioned Sciascia, you’ve just mentioned Pirandello. I’ll tell you, my place in Italian literature is among the Sicilian. I feel very grounded in Sicilian literature, and also in its themes. Also because Arab culture has been part of Sicily for centuries; there are Arab roots in Sicily. I feel very close to Pirandello, the question of humor, pazzia [madness], identity — multiple identities. I feel very close to a writer such as [Vitaliano] Brancati, who critiques society with a light touch, and obviously Sciascia.

Meredith K. Ray: It’s quite interesting, because when you think of Italian giallisti, many of them are Sicilian, or set their books in Sicily. I also see a bit of Boccaccio in some of your works, for example in the comic-tragic love triangle in Divorce Islamic Style.

Amara Lakhous: Yes, that true. That’s a great reference. Let’s just say I’m in good company.

Meredith K. Ray: I was re-reading your preface to The Bug and the Pirate, which is really wonderful, because it’s so concise and yet so dense with ideas. There, you quote Calvino in saying that “a debut novel always contains the writer’s entire plan, everything that will come after, [his] creative genesis [. . . ].” How has this been true for you?

Amara Lakhous: Certainly, in this desire to recount reality, but with depth. For example, Divorce Islamic Style is, in essence, my doctoral thesis. I wanted to write about Arab Muslim immigration in Italy. I defended it and instead of publishing my thesis, it became the basis for my novel. I’ve always thought of the novel as the result of a long period of study. I think it would be great, in the future, to add bibliographies to novels, like in theses. I could really add one. You can see there’s a lot of bibliographical references in my novels. And they’re important for understanding them. So there’s this desire to describe reality with seriousness and depth. Before writing, I read. I do research, I document things. That’s the first thing.

Second is the work I’ve done with language. There’s a Tunisian critic who wrote a great essay on language in the Arabic version of The Bug and the Pirate. Because I tried to refer there to [Carlo Emilio] Gadda, to classical Arabic, dialect, proverbs, French — I created a language. Leaving in 1995, that project was transformed. I went to Italy. I’m not nostalgic. I think of creativity as a step forward, an exploration, and things can be found again. It’s not impossible that I might go back to Algeria someday. But it was a great experience.

The third thing is leggerezza. Because in The Bug and the Pirate, there are parts that really are light. A friend of mine who read said it made him laugh and cry. They say the same thing about Divorce Islamic Style, Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet. It’s commedia italiana, it makes you laugh and cry at the same time. You’re never indifferent. And that’s what literature does. It never leaves you indifferent. If you read a beautiful book or see a great film, those characters and places won’t leave you easily. When you’re dreaming, when you’re sleeping, when you’re talking with friends — the world is never the same as it was before. Literature, art, it never leaves you empty-handed. It always gives you something. It gives you new eyes, a new perspective that changes you.

Meredith K. Ray: When will the new book be completed?

Amara Lakhous: I’m working on it now and it will be out in September and translated into English after a few months. Also, since something that perhaps interests us both is the theme of the female voice, in the new book, there are dual narrators: a woman and a man. In Clash of Civilizations, that was where I first put myself in the shoes of a woman, because I was interested in a woman’s perspective on the world — because we live in a world narrated by men.

Meredith K. Ray: There’s also a strong female voice in Divorce Islamic Style, which I really enjoyed. Do you have a favorite novel? Or are they like your children — you can’t choose?

Amara Lakhous: My wife says Divorce Islamic Style. Also, this latest one about the Roma is really interesting.

Meredith K. Ray: Do you have a title for it yet?

Amara Lakhous: It’s temporary. But I hope they’ll use La splendida zingarata della verginella di via Ornea. It’s a true story, from a few years ago, where two Roma were accused by a fifteen-year old girl of rape, and after a big hubbub — their camp was burned down — after two days, the girl changed her story. She had gotten pregnant by her boyfriend and her family was very Catholic . . . and they sent her to the gynecologist every two months to make sure she was a virgin. She was scared, and invented this story and said it was Roma. In my novel they start calling her the virgin of Via Ornea, [Via Ornea is a street in San Salvario in Turin,] and then later, the verginella — to mean someone who is cunning. And zingarata is a joke. I don’t know if you remember Amici miei [My Friends, 1975] — they used the word zingarata to mean a joke, and it comes from zingaro [“gypsy”], so I use it. But it’s a temporary title.

Meredith K. Ray: It’s true that you always use very long, descriptive titles. They tell you a lot about the novel.

Amara Lakhous: There are also epigraphs, which are never casual. There are two excerpts from articles from the 1950s in Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet that talk about southern Italian immigration. In this [latest] novel, I put an excerpt from an article published in the New York Times in 1882 that talks about Italian immigrants [to the United States] — they’re dirty, they let their children run in the streets . . .if you take out Italian and substitute Roma, its the same thing.

I work on memory, in this sense. The cycle that repeats, unfortunately.

This interview was conducted in Italian and translated by the author.

April 9, 2014

CLASH OF CIVILIZATIONS OVER AN ELEVATOR IN PIAZZA VITTORIO

Europa Editions, New York, 2008

Translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein

THE TRUTH ACCORDING TO PARVIZ MANSOOR SAMADI (first chapter)

few days ago—it was barely eight o’clock in the morning—sitting in the metro, rubbing my eyes and fighting sleep because I’d woken up so early, I saw an Italian girl devouring a pizza as big as an umbrella. I felt so sick to my stomach I almost threw up. Thank goodness she got out at the next stop. It was really a disgusting sight! The law should punish people who feel free to disturb the peace of good citizens going to work in the morning and home at night. The damage caused by people eating pizza in the metro is a lot worse than the damage caused by cigarettes. I hope that the proper authorities do not underestimate this sensitive issue and will proceed immediately to put up signs like “Pizza Eating Prohibited,” next to the ones that are so prominent at the metro entrances saying “No Smoking!” I would just like to know how Italians manage to consume such a ridiculous amount of dough morning and evening. My hatred for pizza is beyond compare, but that doesn’t mean that I hate everyone who eats it. I’d like things to be clear right from the start: I don’t hate the Italians. What I’m saying is not beside the point—far from it. I really am talking about Amedeo. Please be patient with me. As you know, Amedeo is my only friend in Rome, in fact he’s more than a friend—it’s no exaggeration to say that I love him the way I love my brother Abbas. I really love Amedeo, even though he’s a pizza addict. As you see, my hatred for pizza doesn’t come from hostility toward Italians. In fact, it’s not important whether Amedeo is Italian or not. My concern is to avoid at all costs the consequences of my aversion to pizza. For example, a few weeks ago I was fired from my job as a dishwasher in a restaurant near Piazza Navona when the owner happened to find out that I hate pizza. Bastards. An outrage like that, and there are still people who maintain that freedom of taste, expression, and religion, not to mention democracy, are guaranteed in this country! I would like to know: does the law punish pizza-haters? If the answer is yes, we’ve got a real scandal here; if the answer is no, then I am entitled to compensation. Don’t be in such a hurry. Allow me to tell you that your biggest failing is hurry. Your watchword is impatience. You drink coffee the way cowboys drink whiskey. Coffee is like tea, you should avoid gulping it down—it should be sipped. Amedeo is like hot tea on a cold day. No, Amedeo is like the taste of fruit at the end of a meal, after you’ve had bruschetta with tomatoes or olives, then the notorious first course, which includes all those different pastas I can’t stand, like spaghetti and company (ravioli, fettuccine, lasagna, fusilli, orecchiette, rigatoni, and so on), and finally the second course, of meat or fish with side dishes of vegetables. All things I’ve gotten to know from my occasional jobs in Italian restaurants. I really love fruit, so don’t be surprised if I compare Amedeo to fruit. Let’s say Amedeo is as sweet as a grape. The juice of the grape is so good! It’s pointless to persist with this question: is Amedeo Italian? Whatever the answer is, it won’t solve the problem. But then who is Italian? Only someone who was born in Italy, has an Italian passport and identity card, knows the language, has an Italian name, and lives in Italy? As you see, the question is very complicated. I’m not saying that Amedeo is an enigma. Rather, he’s like a poem by Omar Khayyam: you need a lifetime to understand its meaning, and only then will your heart open to the world and tears warm your cold cheeks. Now, at least, it’s enough for you to know that Amedeo knows Italian better than millions of Italians scattered like locusts to the four corners of the earth. I’m not drunk. I didn’t mean to offend you. I don’t despise locusts; in fact, I respect them, because they procure their food with dignity—they don’t count on anyone. And then it’s certainly not my fault if the Italians like to travel and to emigrate. Even today I’m amazed when I hear speeches by certain Italian politicians on the news and on television programs. Take, for example, Roberto Bossosso. You don’t know who Roberto Bossosso is? He’s the leader of the Forza Nord party, which considers all Muslim immigrants enemies. Every time I hear his voice, I’m assailed by doubts; I look around in bewilderment and ask the first person I see, “That language Bossosso speaks—is that really Italian?” Up to now I haven’t gotten any satisfactory answers. Often people will say to me: “You don’t know Italian,” or “First, you have to learn the language better,” or “Sorry, but your Italian is very poor.” Usually I hear these poisonous phrases when I’m looking for work as a restaurant cook and in the end they shunt me into the kitchen to wash dishes. “It seems that the only thing you know how to do, dear Parviz, is wash dishes!” Stefania likes to provoke me and tease me like that. There’s no question that she’s disappointed in me, since she was the first person who taught me Italian, or, to be more precise, tried to teach me. I’m not Amedeo, that’s as clear as a star in the peaceful sky of Shiraz. But I’m sorry to inform you that I’m not the only one who doesn’t know Italian in this country. I’ve worked in restaurants in Rome with a lot of young Neapolitans, Calabrians, and Sicilians, and I’ve discovered that our language level is about the same. Mario, the cook in the restaurant at the Termini station, wasn’t wrong when he said: “Remember, Parviz, we’re all foreigners in this city!” I’ve never in my life seen anyone like Mario: he drinks wine like water, and it has no effect on him. O.K., I’ll tell you about Mario the Neapolitan some other time. Now you want to know everything about Amedeo—that is, start dinner with dessert? As you wish. The customer is king. I still remember the first time I saw him. He was sitting in one of the desks in the first row near the blackboard. I approached; there was an empty seat near his, I smiled and sat down next to him after saying the only Italian word I knew—“Ciao!” This word is really helpful, you use it when you’re saying hello to someone and when you’re saying goodbye. There’s another word that’s just as important: cock. It’s used to express rage and to calm down, and males don’t have a monopoly on it. Even Benedetta, the old concierge, uses it all the time, without embarrassment. Speaking of which, old Benedetta is the concierge of the building where Amedeo lives, in Piazza Vittorio. This wretched woman has a nasty habit of lurking near the elevator, ready to pick a fight with anyone who wants to use it. I adore the elevator, I don’t take it because I’m lazy—I meditate in it. You press the button without any effort, you go up or descend, it could even break down while you’re inside. It’s exactly like life, full of breakdowns. Now you’re up, now you’re down. I was up . . . in Paradise . . . in Shiraz, living happily with my wife and children, and now I’m down . . . in Hell, suffering from homesickness. The elevator is a tool for meditation. As I told you, it’s a practice I’m used to: going up and coming down is a mental exercise like yoga. Unfortunately Benedetta watches me like a cantankerous cat, and as soon as I set foot in the elevator she yells at me: “Guaglio’! Guaglio’!” (literally=boy) “Guaglio’” is Benedetta’s favorite word. As you know, guaglio’ means “fuck” in Neapolitan. At least, that’s what a lot of Neapolitans I’ve worked with have told me. Every time she sees me head for the elevator she starts shouting, “Guaglio’! Guaglio’! Guaglio’!” In Iran, it’s customary to show respect for old people and avoid bad words. That’s why, instead of answering the insult with another insult, I confine myself to a brief response: “Merci!” I leave and go away without looking at her. By the way, you know that merci is a French word that means “thank you”? Amedeo told me, he knows French well. I met him at a free Italian class for immigrants in Piazza Vittorio. I had just arrived in Rome. Amedeo was different from the others because he went to all of Stefania’s classes, he didn’t miss a single one. At first I didn’t understand why he was so diligent and so good. But passion is like the shining sun and no one can resist its rays, passion is youth’s best friend. There’s a Persian proverb that goes: youth is as intoxicating as wine. A few months later Amedeo decided to go and live with Stefania in her apartment, which overlooks the gardens of Piazza Vittorio, and he also stopped coming to school, since he didn’t need lessons for beginners, the way I did. But we stayed in touch; we met almost every day at Sandro’s bar to have a cappuccino or a cup of tea. Sandro is a nice man, but he gets mad easily. All you have to say is “Go Lazio!” to make him furious, whereas if you’re a fan of the Rome team he treats you like an old friend. Once he asked me if there were any Rome fans in Iran, and not to disappoint him I said, “Of course,” and then he hugged me. Obviously I also saw Amedeo at his house. I’m very fond of his small kitchen. It’s the only place that brings solace to my aching heart. When I think of my children, Shadi, Said, Surab, and Omar, and my wife, Zeinab, I get very sad. Where are they now? Wandering, I suppose, God knows where. How I wish I could kiss them and hug them. Only tears and these bottles of Chianti put out the fires of longing. I cry a lot and I drink even more, to forget my ordeals. I got into the habit of going every day to sit near the fountain across from the entrance to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore to feed the pigeons and cry. No one can take the Chianti away from me except Amedeo, he’s the only one who dares pull me out of the hell of my grief. He sits beside me in silence, lets me cry and drink for a few minutes, then suddenly he gets up as if a snake had bitten him, and says to me in a tone of confusion: “My God, we’re late! We have to make dinner, Stefania’s having a party. Did you forget, Parviz?” He always says the same words, in the same way, with the same seriousness. I look at him and laugh until I’m exhausted, laughing helps me breathe. In the meantime Amedeo confounds me with jokes so hilarious that we laugh like lunatics in front of the tourists. Before we go to his house we stop at Iqbal the Bangladeshi’s shop in Piazza Vittorio to buy what we need for the party: rice, chicken, spices, fruit, beer, and wine. I take a shower and change, and there is Amedeo opening the kitchen door: “Welcome to your kingdom, Shahryar, great sultan of Persia!” He closes the door and leaves me alone for hours. I immediately start preparing Iranian dishes, like gormeh sabzi and kubideh kebab, kashk badenjan and kateh. The odors that fill the kitchen make me forget reality and I imagine that I’ve returned to my kitchen in Shiraz. After a while the perfume of the spices is transformed into incense, and this makes me dance and sing like a dervish, ahi, ahi, ahi . . . In a few minutes the kitchen is in a Sufi trance. When I finish cooking I open the door and find the guests waiting for me in the living room. Then the party begins. Each of us has a place where we feel comfortable. For some it’s a church, for some a mosque, a sanctuary, a movie theater, a stadium, a market. I feel comfortable in a kitchen. And it’s not that surprising, because I’m a good cook. It’s a skill that was handed down to me from my grandfather and my father. I’m not a dishwasher, as they say in the restaurants of Rome. In Shiraz I had a good restaurant. Damn those bastards who ruined me, in the blink of an eye I lost everything: family, house, restaurant, money. People keep telling me: “If you want to work as a chef in Italy you have to learn the secrets of Italian cooking.” What can I do if I can’t bear pizza and spaghetti and company? Anyway, it’s pointless to learn Italian cooking. Soon I’m going back to Shiraz. I know I am. I wonder why the Italian authorities continue to deny what all honest doctors know: pasta makes people fat, and causes obesity. The fat gradually starts to block the arteries until the poor heart stops beating. It even happened to Elvis. You remember how thin and handsome he was when he sang “Baba bluma bib bab a blue . . .” In those days, he ate rice every day, but then, unfortunately, he got used to pizza that he ordered in from the Italian restaurants in Hollywood, because he didn’t have time to cook, to sit down at the table and eat. Poor Elvis had too many commitments, and the result was that in a short time he got as fat as an elephant and died—the fat saturated his heart, his lungs, his eyes, his whole body. No one can contain that deluge of fat. I’ve warned Maria Cristina, the home health aide, not to eat pasta. When I met her two years ago, she was thin, too, then she got used to spaghetti and blew up like a hot-air balloon. Once I said to her, “Why have you abandoned your roots—isn’t rice the favorite food of Filipinos?” Poor Maria Cristina, recently they decided to forbid her to use the elevator, out of fear she’d break it. “You weigh more than three people put together”—that’s how they justified keeping her out. So why doesn’t the ministry of health add to the labels of pasta packages the words “Seriously hazardous to your health”? Amedeo is like a beautiful harbor from which we depart and to which we always return. When I’m sacked from a job I’m like a person who’s been shipwrecked, and Amedeo’s the only one who helps me out. He always says to me: “Don’t worry, Parviz, come on, let’s have a look at Porta Portese.” And so we sit in Sandro’s bar. Amedeo opens the paper and marks the important ads with a little x, then we go to his house to make the phone calls. I stare at him in astonishment, like a child looking at a rainbow. Amedeo is amazing. I listen to him speaking his elegant Italian. After a few phone calls he takes the TuttoCittà, the city guide, and glances at the pages to be sure of the exact street names, makes some notes in his notebook, and then looks at me and says, “The restaurants of Rome await you, Signor Parviz!” We go together to see the restaurant owners, and obviously I say nothing—I let Amedeo speak for me. He’s so convincing, fantastic! Very often I start work that same day as an assistant cook, even if a few days later I’m packed off to wash dishes. It’s hard for me to take orders in the kitchen. I hate being assistant cook, I prefer to wash dishes and put up with the pain in my back and a bit of arthritis rather than take orders: “Parvis, peel the onion!” “Parvis, put the water on!,” “Parviz, prepare the pasta!,” “Parviz, get the carrots from the refrigerator!,” “Parviz, check the spaghetti!,” “Parviz, wash the fruit!,” “Parviz, clean the fish!” For me the kitchen is like a ship. Parviz Mansoor Samadi doesn’t set foot on a ship unless he’s in command, that’s the truth. Amedeo always goes with me to any administrative proceeding, like renewing my residency permit, or dealing with other bureaucratic matters . . . When I went to the city offices by myself I’d lose control at the drop of a hat, and start shouting, and they’d throw me out every time like a mangy dog. They’d yell things like “If you come back here again we’ll call the police!” I don’t know why they always threaten to call the police! Where is he now? Who knows. All I know is that Amedeo will leave a terrible hole in our lives. In fact, I can’t imagine Rome without Amedeo. I still remember that wretched day in the police station on Via Genova, where I had gone to pick up the decision from the High Commissioner for Refugees. The words of the police inspector shocked me: “Your petition has been rejected, all you can do is appeal.” I went into the first bar I came to on the street, bought some bottles of Chianti, I don’t remember how many, and headed for Santa Maria Maggiore to sit near the fountain, as usual, but that time I went to drink and weep. I was devastated that my petition had been rejected, because I’m not a liar. I fled Shiraz because I was threatened, if I go back to Iran there’ll be a noose waiting for me. They took me for a fraud and a liar. But it had never crossed my mind to leave Iran. During the war against Iraq I fought in the front lines and was wounded several times. And then why would I abandon my children, my wife, my house, my restaurant, and Shiraz, except to avoid being killed! I’m a refugee, not an immigrant. Ah no! This is an important fact, it has to do with my friend Amedeo. I told you, I wept for a long time, and I drank a lot of wine, and then I had a clever idea. I went back to the welcome center where I lived, got a needle and thread, and carried out my plan. I still remember the social worker’s cries: “Oh my God, Parviz has sewed up his mouth!” “Oh God, Parviz has sewed up his mouth!” Many people intervened, they tried to persuade me to back down, but I refused. They called an ambulance, the doctor tried to make me stop, but it was useless. After several attempts, lasting for hours, they called the cops, who tried by every possible means to take me to the hospital. But I resisted with all my might. I closed my eyes and it seemed to me that I was sleeping near the mausoleum of Hafiz in Shiraz, the way I did as a child. I made a tremendous effort to convince myself that everything that was happening was just a bad dream or a delirium caused by alcohol. Then I opened my eyes to a policeman who was shouting and waving his club, saying: “Either you go to the emergency room on your own or we put you in a straitjacket and take you to the psychiatric ward.” I said to myself, “The only way I’ll move from here is inside a coffin.” I closed my eyes again as if I were a corpse. At some point I felt a warm hand, and I struggled to open my eyes. In front of me I saw Amedeo. It was the first time I’d seen him cry. He embraced me the way a mother embraces her child who’s trembling with cold because he was caught by surprise in the rain on the way home from school. I cried for a long time in his arms, in a flood of tears. When I stopped, Amedeo went with me to the emergency room, where they removed the thread from my mouth, and with great difficulty I started to breathe again. Amedeo insisted that I spend the night at his house. The truth is that Amedeo is the only one in this city who loves me. It’s impossible! Amedeo a murderer! I will never believe what you’re telling me. I know him the way I know the taste of Chianti and gormeh sabzi. I’m sure he’s innocent. What does Amedeo have to do with that thug who pisses in the elevator? I saw him with my own eyes, I said to him: “This is not a public toilet.” He gave me a look of such hatred and said, “If you say that again I’ll piss in your mouth! You’re in my house, you have no right to speak! Get it, you piece of shit?” And then he kept shouting at me, right in my face: “Italy for Italians! Italy for Italians!” I didn’t want to argue with him, because he’s crazy. Have you ever heard of a sane man who shamelessly pees in the elevator and is called the Gladiator? Frankly I wasn’t sorry about his death. That Gladiator kid isn’t the only lunatic in the building. Amedeo has a neighbor who calls her dog sweetheart! She treats him like a child, or a husband; in fact, once I heard her say that he sleeps next to her, in the same bed. Isn’t that the height of madness? God created dogs to guard the flocks, to protect them from wolves and keep away thieves, not to sleep in the arms of women! Look for the truth somewhere else. I’m suspicious of that young blond guy who lived in the same apartment with the Gladiator. He has to be a spy or an agent of some secret service. I’ve often seen him follow me and watch me from a distance feeding the pigeons at Santa Maria Maggiore. Once he overwhelmed me with a lot of odd questions: “Why do you like pigeons so much?” “Why do you always use the elevator?” “Why are you always drinking Chianti?” “Why are you so friendly with Amedeo?” “Why do you hate pizza so much?” So I yelled right back, “What do you want from me, you spy?” Goddam spies, they’re always tracking down secrets! At that moment he looked at me in surprise: “Don’t you understand that I need all this information about your life for my film.” Amazed, I asked, “What do you mean?” and he said, “I’m talking about the film I’m making, and you, Parviz, are going to be the star.” That’s when I asked myself, disconcerted, if this damn blond guy was a spy or a lunatic. When I talked to Amedeo about it, he smiled: “Parviz, don’t be afraid of the blond kid, he dreams of becoming a film director someday. Human beings need dreams the way fish need water.” I didn’t entirely understand what Amedeo was saying, but it doesn’t matter, what really counts is that I trust him completely. I’m sure there’s been a mistake. After that business of my strike against talking, Amedeo persuaded me to file an appeal, taking responsibility for the expenses. After a while they re-examined my case and admitted that I had been telling the truth, that I hadn’t lied. And in the end they granted me political asylum. Besides, I’m frank and honest because I have nothing else to lose—I’ve already lost my children, my wife, my house, my restaurant. Let me say that I don’t have much faith in the Italian police. So many times they’ve hauled me in to the police station to interrogate me like a dangerous criminal! What I’m saying makes a certain amount of sense. Answer my question, please: is feeding the pigeons a crime punishable by Italian law? Now let me explain: as you know, Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore is a place where pigeons like to gather. I love the pigeons, I feel happy when I feed them. A man surrounded by pigeons is a sight that arouses the admiration of tourists, and inspires them to take souvenir pictures. And so I contribute to the promotion of tourism in Rome. But that doesn’t protect me, because on more than one occasion the police have prevented me from getting near the pigeons. I’ve objected: “What’s the law that prohibits feeding the pigeons?” I’ve done my best to explain that the dove is the symbol of peace in all traditions, it’s even the symbol of the United Nations! I wonder how Italy can keep me from feeding the pigeons if it’s a member of the UN. The police mistreated me even though I hadn’t done anything serious, in fact they insulted me by saying, “You want to make beautiful Rome into a garbage dump? Go back where you came from and do whatever you want there!” I refused to give in to their threats and I kept fighting, I swore to remain faithful to the pigeons. I’ll never let them die of hunger. Amedeo acted as a mediator between me and the police and they made me feed the pigeons with food provided by the city. I didn’t understand the point of this agreement, but what’s important is not to have any more trouble with the police and to be able to get the food without spending a cent. But forget the abuse I get from the police. Let’s talk about the concierge Benedetta, who won’t stop being a bitch, just to annoy me. One time I lost patience and said to her, “It’s disgraceful for a woman your age to say guaglio’!” but she went on repeating it shamelessly. The insults of that wretched woman have no rhyme or reason. Once she asked me, rather arrogantly, “Do you eat dogs and cats in Albania?” I kept calm, and answered her, “Do you know Omar Khayyam? Do you know Saadi? Do you know Hafiz? We are not savages who eat cats and dogs! And what the hell do I have to do with Albania!” I’ve been brought up since childhood to respect old people, that’s why I walked away from her saying, “Merci, Signora.” But let’s get back to Amedeo. He’s not the murderer! He can’t have had anything to do with this crime. Amedeo is not stained with the Gladiator’s blood. I’m sad because of his absence. I don’t know exactly what’s happened to him, but of one thing I’m sure: from now on no one will take any notice of me when I cry and drink wine in Piazza Santa MariaMaggiore. Who will take the bottle of Chianti away from me? I’m thinking seriously of leaving. If Amedeo doesn’t come back in the next few days, I’m leaving Rome and never coming back. Ladies and gentlemen, Rome, without Amedeo, is worthless. It’s like a Persian dish without the spices!

Also, read an interview of the artist from Odisha, Ramakanta Samantaray, published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

0 Comments