Translated from the Classical Chinese by Xiaoqiu Qiu

Thinking About Dao Priest Zhiti

sitting by the green water, I thought about my dear friend.

If only we lived in one place,

we need not miss each other.

The clouds on the water flooded my threshold,

the spring thunder scattered between the branches.

I have a lifetime of endless things,

how can I bear

Twenty-Four Mountain Poems, No. III

good birdie,

sitting on moss, grabbing my nipples

good tea.

I only saw bears

strolling in rows.

In the beginning, the best of poetry

excels that of music;

at the end, the truest truth

emulates that of an infant.

Not that these virtuous spirits of old

Have gone like the wind:

It’s just that few now knows

That they have not.

Five Poems of Spring Wilds

1

Light steps upon light teal, an expanse

of green

Running water alongside chariot, chasing

one another

Carrying a slingshot, little men

from which house?

Aiming it true at the red robe

of a woodpecker.

2

Mountain flowers, rain hits all away

Over the ground, mushy brocades

Looking far for partridge chicks

Yet picked up a lump of fungus.

3

Old bull ploughs the field, in pain

Calf’s eyes look up, as if sob

All things are Heaven’s plan:

The overgrowing weeds huddling up

Like heads.

4

Slanting sunbeams ruin

-ous mound,

Half out of the dirt, a

skull.

Don’t know whose son,

laying

There, spiriting still

Alone.

5

Young bull skinny

Bull girl small

Leaving the bull rope

To play sport

Yet the old man with his hoe

is again too old:

dim dim light smoke

cloaks mulberry grove;

a drunk painter would come,

and without order, sweeps everything

under his brush.

Twenty-Four Mountain Poems, No. XV

Among the hundred cliffs and thousand ravines,

an uneven path,

a drizzle blurs the cypress,

I alone close the door.

The herb boy disappears

into the valley stream,

the flower bee braves

the light smoke at dawn.

Walking idly, let go my mind

in search of gone water,

Sit still, hold up my chin

until the rays of sunset.

I always remember Master Nanquan’s great words:

the students of the Way are rarely

as stuporous and as slow as him.

Twenty-Four Mountain Poems, No. IV

Only in forgetting why

gives splendor to human minds:

green lotus wraps around

sun setting slant.

Deep and secluded

a path leading to a celestial cave:

alone and quiet

no one to fall a flower petal.

Flashing thunder, drifting clouds

Are easy metaphors,

Yet phoenixes or dragons

Need no further comparisons.

Take a look

at the riverside tombstones of heroes:

pine trunks and cypress timbers.

Translator’s Note:

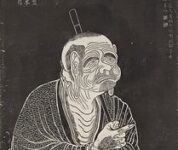

Monk poet Guanxiu (832-912) was a renowned Chan (Zen) Buddhist hermit, wanderer, and artist of many disciplines at a turmoil time in Medieval China. Like many Chan monks before him, he embodied poetry in his religious meditation and vice versa. Unlike those hermits of peaceful times, he wandered the war-torn landscape in the aftermath of one of the most tragic periods in human history—a civil war that decimated up to 80% of the people of the most populous country on earth then (est. 50 million). Reflecting on this drastic social change, he was one of the first to break through the old poetic conventions, as we see him experiment with more vernacular tones, more humanistic perspectives, and more variable musical patterns. Five Poems of Spring Wilds is a good example of how he combined traditional forms of regular line lengths and landscape poetry with a subtle yet chilling twist of imagery of the aftermath of war and how common people had to bear its consequences. No translation has been published in English but I believe he has tremendous relevancy today. Many difficulties lie in translating from Classical Chinese, including its grammar, rhymes, and ambiguity—it is no less than reinventing them in English. I aimed to respect its musical patterns by and large but at times be loyal to its imageries by utilizing more line breaks and spaces.

Also, read five poems by the Italian writer, Antonia Pozzi, translated into English by Amy Newman, and published in The Antonym:

thoughtful and reading worthy. Thanks