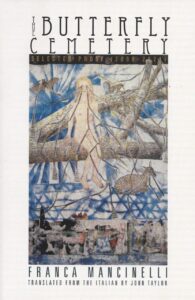

When Franca Mancinelli and I meet, memory captures our words, time expands, fragments, then come back together in a new cloud of moments. Some of them settle: the dust of childhood, enchantments, wounds, the stylistic maturity of her writing in which everyday life and poetry merge to hover in an essential space full of that naturalness that is so difficult to achieve. She reveals much about this approach to writing in her bilingual collection of autobiographical narratives and personal essays, The Butterfly Cemetery: Selected Prose 2008-2021 (translated by John Taylor, published by The Bitter Oleander Press, 2022), which has not yet appeared in Italy. I have just had the privilege of reading it as well as her fourth book—a bilingual collection of interwoven poetry and poetic prose—also available in Taylor’s translation: All the Eyes that I Have Opened (Black Square Editions, 2023).

Domenico Segna: The Butterfly Cemetery collects prose writings that beat their wings like genuine poems: a perfectly successful flight. Why such a tense title?

Franca Mancinelli: “The Butterfly Cemetery” is the title of the opening story, which is set in childhood. The word “cemetery” can immediately evoke something mournful, but the image of butterflies leads, at least in my view, to place of fairy tale and mystery where death does not have a tragic or dramatic meaning. Moreover, a cemetery rather resembles a garden in which a kind of beauty (which had previously gone through the air) has settled. Perhaps this is also because butterflies, in various cultures, have been associated with metamorphosis, with what does not die but instead is transformed. The title refers to one of my childhood games based on the “magic dust” that lies on butterfly wings. By touching their wings, I ended up “taming” the butterflies yet, without realizing it, killing them. So, I would bury them inside a circle of white stones which, in time, formed a small cemetery. When I returned to this memory through writing, the image began reverberating, leading me to that which requires distance in order to live, to that which will be destroyed if we touch it. Something similar happens with rainbows. But we humans are also evanescent, fragile creatures, and much in us must die and be buried every time we are touched by unconscious hands. I ultimately chose to give this book of prose writings the title of this opening story because in that image I also recognized the experience of writing. By writing we try to capture beauty, but we cannot help but kill it: every time we shape and confine, life, with its beauty, loses not only its energy but also the open space from which it comes, and it enters one of its deaths. This is why a poem, a written page, is our butterfly cemetery.

D.S.: Autobiographical pages are juxtaposed with pages that little by little discover the value of words. This revelation is like a painful laceration for you yet, at the same time, you rigorously present what makes up your memory: you write because you have “yielded words,” as you put it. Yet in this “fall” or “loss,” about which you write, you have found a blade of grass. What is it?

F.M.: It is what is totally unexpected. It is a vital energy that emerges in a place that seemed inhospitable. And then the sprout, the blade of grass that has found a way to be here, transforms everything surrounding it and becomes the center, the unknowable that lives between cracks and cavities. The loss about which I write in “Yielding Words” is an experience of losing oneself, a form of transparency experienced with one’s own body. I experienced it in childhood and then especially in adolescence, during those years in which it is easy to find oneself on the edge of the circle of one’s contemporaries. I continue to experience this form of disappearance, of an absent presence to one’s own registered name and personal identity, when I am writing. At those times, I can forget my human contours and be embraced by that original love that passes into us through language, as if by means of an ancient umbilical cord. I can also experience this in nature, beneath the foliage of my “guardian trees” or below the surface of the sea. Experiencing it among humans, however, raises great risks and is a source of danger and destruction. I speak about this in a personal essay, collected in the book, with the title “Poetry, Mother Tongue”:

With poetry, we are led back to who we really are, to our most genuine face, which is a dark open face in which a leaf, or the snout of an animal, can emerge.

There are states of our being in which our boundaries become so labile that they can be crossed easily. For a few moments we are what we see and hear. It is a condition of extreme fragility, in which we are exposed to an enormous risk. Over time, through writing, I have been given the opportunity to reverse the direction and the meaning of this broad self-destructive potential around which I was gravitating: this is how I found myself within the poiein, within the possibility of creating, of changing something through myself. By doing so, I draw on the force released from that short-circuit between death and life. It’s like an electric shock that reminds me, in an instant, of everything that I have had to sacrifice to the darkness. It reminds me of the other side of the mirror: my buried loved ones, the missing, and the nameless. Everything that still asks for a voice and calls out.

D.S.: In the book, “Poetry, Mother Tongue” offers a dazzling moment of your poetic journey. I’d rather let you speak than ask you a question that might seem to be a display case containing a dead butterfly.

F.M.: The final section of The Butterfly Cemetery consists of personal essays in which I reflect on the experience of writing and the meaning of poetry. Written on various occasions, they are prose texts gathered thanks to the care of my American translator John Taylor, to whose fraternal closeness this book owes its existence. Even though we speak two different languages on a daily basis, John and I have the same mother tongue: poetry. Recognizing ourselves as children of a language (and, in particular, of the language of poetry) offers a possibility of solace and salvation. This possibility is open to each of us. In this way, we belong to a family as extensive as the cosmos. The love that circulates has no conditions and restrictions; it simply asks to be perceived and transmitted. As children of this language, we remain infants throughout our existence, searching for the name of each thing, trying to spell it exactly. We are brought into the world every time a word reaches reality, makes it exist. In regard to our wounds, poetry provides a form of redemption, of repair: its transformative power brings us back to life. This is expressed in one of the poems from Gleams, a sequence found in my most recent book of poetry, All the Eyes that I Have Opened (Black Square Editions, 2023):

with the power of nothing

of never having had

anything to barter,

gestures re-create a language

fastening armor to my body.

It is a strength that comes from being disarmed, from the most complete nakedness, from the awareness of one’s own fragility, of being nothing. It is the strength of poetry which, without giving in to any compromise (of understanding, of communication) and with its words which are creative acts, gives us the only armor that we can wear the world.

D.S.: In “A Book of Poetry: A Living Structure,” you record a phrase written by Remo Pagnanelli: “Purity is a flag of mourning.” The text continues: “Purity, like perfection, is a death sentence.” Who is the judge?

F.M.: This line is taken from one of Remo Pagnanelli’s poems in Holiday Preparations (Preparativi per la villeggiatura), the testamentary book of this poet from the Marches region who left on vacation from existence in 1987, at the age of thirty-two. Purity, like perfection, is one of the flags that we can find ourselves carrying, more or less consciously, into existence. Pagnanelli’s line probably resonated with me because I was reflecting on errors, in those same short prose writings from The Butterfly Cemetery, and, in particular, on the fact that the condition for not making errors is death. Purity and perfection are two very heavy flags to carry; they limit and condition every one of our movements, but at the same time they are not easy to put down. However, we may suddenly realize that we are fighting with all our might under the ensign of death. The ideals created by our mind, like banners, are doomed to fall or inevitably get dirty, to come back into contact with the matter of which everything is composed. The inner judge who has raised these flags, and who defends them from every attack, is destined to remain silent and stand aside so that life can happen and unfold in all its vigor.

D.S.: In the same poetic prose text, there is, after the figure of the inner judge, the portrait of a friend of yours who had learned to knit in a particularly critical period of her life. I think that she taught you a lot.

F.M.: From every friendship and genuine encounter we learn something that is necessary for us, perhaps in particular from those people who bear witness to a difficulty that they have overcome, a ford that they have found where the path was cut off. Through this friend I reexperienced the meaning of a ritual gesture that I had observed many times as a child, in my mother, who knows how to knit, and in my grandmother, who also had a treadle sewing machine. I recalled the generating force of a small repetitive movement that carries life forward in spite of every obstacle, every apparent paralysis. It is a gesture that recalls those community activities carried out by peasant families in the farmyard, such as shelling in silence, singing, or occasionally telling each other something. As in writing, one who sews, weaves or knits is never alone because his or her work joins those who came before and those who are coming, and this allows the thread to be taut, the work to be completed and have a destiny. Thanks to your question, I now resee another habitual gesture that my grandmother used to make, sitting with her hands clasped on her dark apron, turning her thumbs successively to one side and then reversing the direction, like a small wheel continuing to grind its seeds. This how she accompanied the flow of life in moments of apparent emptiness and inactivity. And I also see again an object to which I am very attached and which represents her legacy for me. It is a small wooden chest of drawers that contains spools of different-colored thread, arranged in the order of ever-lighter shades. Many of those spools are still intact. I think of my grandmother’s shy, taciturn personality, of her beauty similar to that of a violet which appears only to those who know how to pay attention and get closer. Her industrious silence is intertwined with the silence of my writing. Her spools unwind in my words. “Maria, towards Cartoceto” is a prose text dedicated to her in The Butterfly Cemetery:

Among the series of sounds that she repeated by heart were prayers. Besides these, she taught me a gesture that resembled that of tying shoes: a crisscrossing movement if performed exactly. The fingertips touch the center of the forehead, the center of the chest, the left shoulder and then the right one. Like a string that ties you together, that pulls you back to the center of your heart, which is always someone else’s heart. Whenever something begins, whenever you head off somewhere, you make this sign of the cross, as if you were on a shore, on wet ground, in front of misty glass or anything else that might be written on. It means: I’m here, at this exact point. And also: I entrust myself to this time and to this space, to this moment and to this place. Don’t let me go astray, keep me closely in sight.

I cannot say who might read this message. I know it’s a sign that soon fades away, that we have to repeat all over again. It’s a bit like tying your shoes in the morning to go out. If later, during the day, you find them untied, you cannot go on very far; you have to stop for a moment and retie them.

D.S.: The invisible: this is what poetry lives on. What pen does it need to bring it back to the white space?

F.M.: The pen writes and at the same time it allows the detachment from the earth and enables the flight, the possibility of looking up at things. The “pen” is also “pain,” as Franca Grisoni recalls in a poem written in the Sirmione dialect, in which the word “pena” (“pain”) indeed also means “penna” (“pen”), that is, transformed pain, pain that is engraved inside our body and on the blank sheet of paper. It is the first tool with which we, as children, left marks, on wet soil, on moist panes of glass.

And it is also a cut branch, a palm leaf of martyrdom, as I was reminded by a polyptych by Crivelli in which Saint Lucy is portrayed. In that painting, Lucy holds her palm in the same way as one might hold a pen; it almost seems that she could dip it into the dish which she carries in her other hand and in which, instead of ink, lie two eyes that she has lost or received as a gift. To her I dedicated a sequence of fragments, December 13th, which are found at the center of All the Eyes I Opened. I initially thought that these poems would not become part of the book, because they were too linked to the occasion that had given rise to them, but then, as if my eyes had suddenly cleared, I realized that they instead somehow formed the very point of light of the book, and that everything in it fell under their guidance. That green pen, that palm leaf, write in the invisible as if on a blank page. It is the pen that a dark angel has dropped.

D.S.: What is the blank space that Franca Mancinelli likes the most?

F.M.: It is the blankness that is always reborn from the act of poetry, from the poem. More than prose, poetry leaves space for the reader as well as to the other who we are, have been or are about to become. Poetry carries deeply within itself the traces of the abandonment to the fall that enables an end and a rebeginning, and therefore it condenses many lives who approach our lips so that they can be expressed and then withdraw into silence, with a rhythm similar to that of sea waves.

*This interview will be published in Italian in the review I martedì, No. 361, anno 46 No. 4, 2023.

Also, Read “The Delicate Dance that is Translation” A Conversation with Daisy Rockwell, Interviewed by Rituparna Mukherjee and Published in The Antonym:

The Delicate Dance that is Translation— A Conversation with Daisy Rockwell

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments