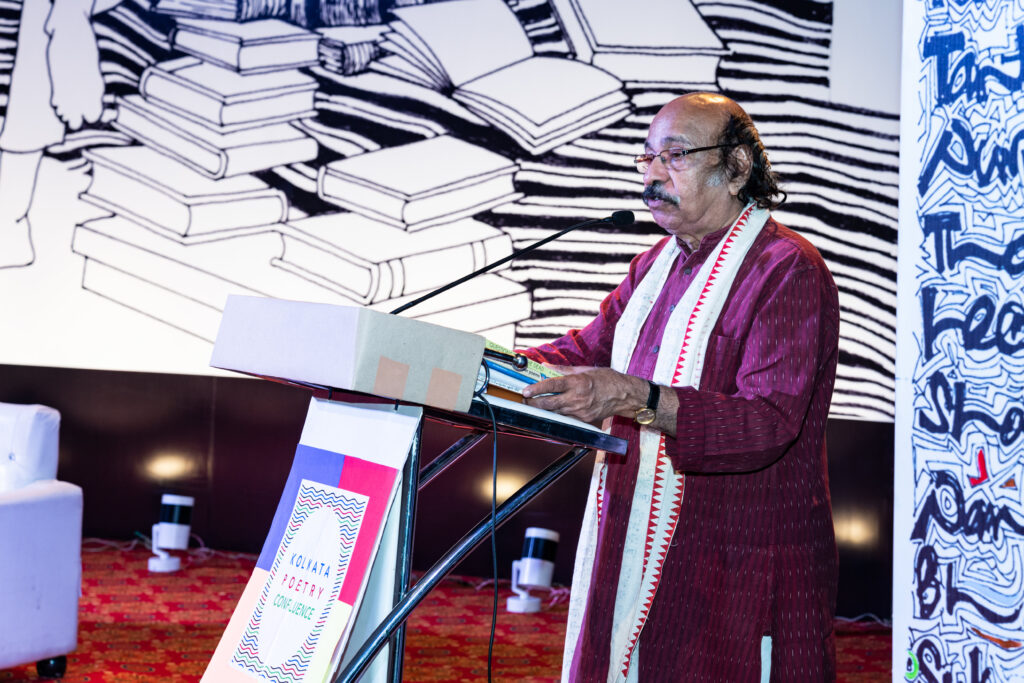

K. Satchidanandan is a bilingual poet, translator, literary critic, and columnist. He writes in Malayalam and English, although Malayalam, his native language, is closer to his heart. He is the former editor of the Indian Literature journal and the former secretary of Sahitya Akademi. He was an esteemed guest at the Kolkata Poetry Confluence held in June 2022. At the confluence, which was jointly organized by The Antonym & Bhasha Samsad, Satchidanandan recited his own poetry, in original as well as in translation. During his visit to the city of joy, Aritra Sanyal of The Antonym engaged in an in-depth conversation with the poet. The literary rendezvous touches upon many significant explorations into the heart of poetry, the process of writing, and the act of translation.

Aritra Sanyal in conversation with K. Satchidanandan

Aritra: For obvious reasons, most of your admirers across the globe have never read you in Malayalam. The two collections, While I Write and The Missing Rib are the books where we get to read your works translated by you. In that sense, how close are we to reading you in original?

Satchidanandan: This is not really for me to say. But I personally have treated my poems as somebody else’s poems while translating them. I did not take any extra freedom just because I happen to write them. I regularly translate poetry— sometimes from Hindi, and a lot from Malayalam, into English. It is a similar kind of freedom that I take with my own poetry. So, I would say that it is very close to the original. But obviously, as you know, Malayalam is a Dravidian language. It has its own grammar and syntax, its own tones and rhythms, which might have got lost in the translation. But I have never believed that there is a complete loss of meaning in any translation. If it’s good enough, if it captures the images well, if it has most of the thoughts and feelings that the poem tries to convey, then there is not much loss! But there is a sort of replacement of the tone of Malayalam with the tone of English, which belongs to a very separate language family. Sometimes, there is also a change in the syntax. This is because, in Malayalam, the order of a sentence is the subject, the object, and the verb, while in English, it is the subject, the verb, and the object. These kinds of inevitable changes will be there in my translation. And, at times, I do write in meters- maybe a regular meter, sometimes I invent meters, sometimes I go back to folk rhythms when the theme demands it. I find such poems extremely hard to carry into English. So, I don’t translate them at all. In fact, some of the poems for which I am very well-known in Kerala have not appeared in English. So, I cannot claim that somebody who reads me in English gets all that I have written, or understands everything I’ve written. But I am sure, a reader gets a very good idea of what I am trying to do. These are not perfect translations but I have tried to be as faithful as possible to the original.

Aritra: Most probably, it is the translations of the classics about which Walter Benjamin mentioned the idea of the ‘afterlife of a text’. (“a translation proceeds from the original. Not indeed so much from its life as from its “afterlife”…)

We cannot deny that even when poets translate themselves, their translations, no matter how immediately done, come invariably after the originals have been composed. Is it also not an afterlife of a text, the extension of its existence on a different plane or language?

Satchidanandan: Yes, it certainly is, because a translation can only happen after the original has been written. In that literal sense, it is an afterlife. Also, in a figurative sense because some of the aspects of the poem are going to live on, make themselves accessible to those who do not know the original language, which, in this case, is Malayalam. It is an afterlife in a spatial as well as a temporal sense. In a temporal sense because it happens after the original. But also, in a spatial sense because generally the life of a Malayalam poem is limited to Kerala or places where Malayalis live. There are no places that Malayalis don’t live in, by the way! But other people who don’t know the language somehow get an opportunity to have at least an idea about these poems. In that sense, it also becomes a spatial afterlife.

Walter Benjamin, in his book, Illuminations, said that translation is like calling into a forest and getting an echo back. This idea of Benjamin has intrigued me because it is not exactly the call that comes back, it is only an echo. So, what he calls an ‘afterlife of a text’ is also, in a sense, an echo of what you had originally intended or written. So, a translated poem is not a sound but an echo; it is not life but the afterlife.

I have so many things to say about translation. But I think these two ideas are extremely important for me. And the third thing that he has said, which has always intrigued me, is that a translation should look like a translation and not like the original. Perhaps, he was compelled to say this because no translation can completely look like the original. So, he said that any translation should leave some marks to show that this was not written in the original. But I cannot say for sure whether this is completely true about my translations or not. This is because there are poems that are somewhat universal and they might look like the original even in translation. But there are poems that are local, local in color, which are located in Kerala. I have quite a few poems in Malayalam, my own language. I have a series of poems about the poets who wrote before me, who I admire a lot, and all of them were my canon. These poems, I believe, are very hard to translate into English. So, I have not tried translating them at all as they might require a lot of footnotes. Even with all those footnotes, all the allusions, the references will not be understood. That is because, sometimes, I refer to a certain poem or particular phrases used by another poet. It becomes extremely difficult to communicate that to somebody who does not understand the language. If at all I tried to translate these, it can only look like a translation. I will have so many footnotes and you will have no many names that you haven’t heard of. Even, in some of my translated poems, you will come across such names where I was compelled to give footnotes. I have reference to Kumaran Asan, who lived in Shantiniketan and wrote one of his famous poems when he was in Kolkata. There were other poets like Edasseri Govindan Nair, Vylopilli Sreedhara Menon, and Changampuzha Krishna Pillai. I have some references to these poets even in the poems that I have translated where I just tell the people who they were because I can’t do more. So, there are poems that look like the original to some extent. But there are some poems where the marks or the scars of the original remain on the body of the translation.

Aritra: You have translated Kazi Nazrul Islam, Pablo Neruda, Mao Zedong, Bertolt Brecht, Ho Chi Minh, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Federico Garcia Lorca, Cesar Vallejo, Sitakant Mahapatra, Kamala Das, Kabir, and Hindi poetry, etc. Has this extensive process of making different texts of varied flavors happen in Malayalam influenced your poetic diction in your original language?

Satchidanandan: It is not yet clear to me whether I was translating them into my style and my idiom or whether they have, in some sense, impacted the writing of my own poetry. I have been asked this question several times. It is quite natural to ask this question because some people may say that they find the influence of Pablo Neruda on some of my poems, especially the love poems. Or, they may say that some other poets have influenced my poetry. But I personally believe that I have translated these poems into my own style even though I have kept in mind the original compositions and the poets’ ways of composing poetry. For example, I translated Kabir recently. In fact, during the entire Covid season, I had been translating the Bhakti and the Sufi poets. I translated Kabir, Bulleh Shah, Basavanna (who was a Kannada Shaivite poet), and Tukaram– the whole anthology of 50 Bhakti poets, many of them women, including Lal Ded, the Kashmiri Bhakti poet. For me, it was kind of a spiritual solace on one hand, and on the other, it was also an attempt to counter the idea of religion, spirituality, and the idea of Hinduism that is being sold in the political market today. While translating these poets, I also had in mind the forms that they used. For example, Kabir wrote bijak, dohas, and ulat wasiya— forms that were very unique to Braj poetry. I translated them directly from his original with the help of some interpretations. Then, I also read them aloud and tried to capture the sound of those lines. This was true about most of the other poets too. I also translated from languages that I do not know, for example, Tukaram. In those cases, I ask my friends like Chandrakant Patil or some of the Marathi poets I know to read Tukaram aloud to me even though I was mostly using the translations of Tukaram, especially by Dilip Chitre, for my own translation. But, I would hear the poems being spoken by a poet in a particular language. Not that I could reproduce that tone or that rhythm entirely but I could capture something of that, at least to the readers of Kabir.

So, I believe that I have been translating most of the poets into my idiom rather than me being impacted by them. I am not denying that they may have obliquely or indirectly impacted my own writing. But when I translate Neruda, I am creating my own Neruda. I am re-writing him in my own style. But many Malayalis think that Neruda wrote in a particular kind of style, and because I was translating him into my own style, they think that there is some sort of connection between his poetry and my poetry which is not true. However, I have been impacted by a lot of poets like all poets have been, whether they admit it or not. Because I have been a very avid and regular reader of poetry, old and new. So, it’s quite possible that all of them influenced me somewhat. But I don’t think anybody can point to a particular poet and say that I am writing like him/her. This has happened mainly because I translated a lot of poets into Malayalam and I translated all of them into my own style, keeping in mind their own distinctive ways of speaking, uttering; their distinctive ways of using tones, images, and meters.

Aritra: You did not have any ‘poet-predecessors’ when you started writing, but, as you entered the tradition of Malayalam literature— the word ‘predecessor’ must have attained a deeper meaning to you. Elsewhere, you discussed poet Ayappa Panicker’s contribution to Malayalam prose-poems, a form which much later came to prominence during the turbulent time of the 70s. It was when you and your contemporaries had already ventured into experimental writings. What should the poets who want to attempt something radically new be clear about— things they want to reject or things they want to write? Negotiating with the tradition, of course, leads them further into a complicated relationship with their predecessors.

Satchidandan: Yes, I think the word ‘complicated’ is extremely important here because nobody writes a poem in order to reject it. I don’t think any genuine poet would ever do that. But when you have new things to say, new experiences, or feelings to convey, you find a lot of inadequacy in the style that was being followed by earlier poets. So, you want to overcome that inadequacy and create a style that is adequate to your own needs. It could be your subjective needs or the needs of a particular period in the history of poetry. You are reacting to demand- an inner demand primarily, and secondly, an outer demand which is the demand of the history of poetry. Because poetry has always been renewed even though we easily give them names or categories. This is why I keep saying that I am very suspicious of names like modern, postmodern or post-postmodern, etc, even though I used to champion some of these terms and movements earlier. But as I matured, I found that perhaps even modernity is not the name of a particular style or movement but it is a way of remaining relevant at all times. As I was translating Kabir, I found Kabir extremely relevant. Kabir was speaking to me. Mirza Ghalib was speaking to me. Shakespeare was speaking to me. Even now, when I read Hamlet, I feel like that. There are poets who have remained with renovations. These may not be in the same form. Like Barthes says, the texts change but you re-read them, and you interpret them with the backdrop of your own personal experiences and the experiences of the particular time. So, I am not saying that Hamlet which Shakespeare had written for the Elizabethan stage is the same as the one we read today. It may be a different Hamlet altogether. It may be the modern man who is also at crossroads, not knowing “to be or not to be”. But they do remain, which means that they lend themselves to different kinds of interpretations. Thus, they remain alive. In some sense, we can respond to them even today. It is in this sense that I define modernity today. It is not something that is being written now. It could have been written earlier but it is something that remains alive, vibrant, living, and dynamic— something that speaks to me even today. To come back to the main point, no poet writes in order to reject a tradition or fight a particular poet. A poet invents, redefines, or, innovates a style as a response to his/her inner needs. There is this need to express something which you feel has not been expressed, something that modern life has given you. That calls for a new way of seeing things. Objectively, this also becomes a demand of poetic history because if we look at the history of poetry, we’ll find that it is actually a series of innovations. It is not that we were the first to invent new forms. Almost every major poet has invented his/her form. So, what we call tradition is nothing but the history of continuous innovations that have been happening in the history of poetry. I am sure A.K Ramanujan and T.S Eliot would agree with me.

Aritra: How has the process of writing changed for you over the years?

Satchidanandan: In fact, it changes in some sense with every poem I write because the demands are often different. I often tell my younger poets who consider me a master of poetry that I am a beginner. In front of the vacant page, I am at a loss. I really do not know what I’m going to write. I have something moving me, something disturbing me, something inspiring me, or, maybe making me feel very uneasy. But until I put it down, I do not really know what language, what words, what syntax, what structure, or what images I am going to make use of to articulate that particular experience. That’s why I say that with every new poem, a poet is reinventing himself/herself. Of course, critics have tried to divide my work into periods as they did with Picasso by looking at the colors which he used. Not all critics did that. Some critics used to say that there was an early stage when I was beginning to write modern poetry when I was experimenting with prose and free verse, free rhymes, and sometimes inventing new metrical patterns; that was in the ’60s. Then, there was a second phase in the ’70s when I was a political radical. I was very sympathetic to the radical movement even though I never participated in it. I found it very difficult to agree with everything that any party or movement did or does even now. But I was sympathetic to it like most young people during that time. We wanted to change society. We wanted a more egalitarian, more just society. I thought that this struggle might contribute to it. If not the creation of that society, then at least creating that aspiration to create that society.

Aritra: When you are writing, what generally comes to you first: an image or an idea?

Satchidanandan: This varies from poem to poem. There’s one instance where I almost heard the poem being sung in the voice of a woman poet; a real woman poet, Sugathakumari who was one of my senior poets. I heard her speaking to me. This was a poem called Bodhavati which has not been translated. It has something to do with Tagore’s Chandalika. We also have a Malayalam writer, Kumaran Asan who has written a poem based on the same story. It’s called Chandalabhikshuki. My poem was a re-creation of the story of Chandalika in a modern context. So, I had heard this poem of mine like somebody was dictating it to me and I was just a hand writing it down. But there are some other poems that came to me almost wholly, especially some poems which are sung. For example, one of the poems which almost everybody in Kerala knows. It is like a folk song; many people think that it is a real folk song and not written by somebody; that came to me as a complete poem and not as a single image. It started with a single line but it kept developing. It is about sharing a bird. It’s like you are preparing a chicken; you cut it and then I request the person and compare it to a particular scene etc, and finally, I say that you can take the bird but give it back to me; that is how it ends. It’s a satire about selfishness. We pretend that we give everything to others but finally we take all of it back. So, there are poems like that.

Sometimes, it comes as a single image, as you have said. Very often, it’s a single image that comes; sometimes I develop that image or it proliferates- many other images come out of that particular image. And sometimes, it is a line or even a title that comes to me. Most of these things happen in the early morning hours, in my case. It may not be the case with everybody. Early morning means 3 o’clock or 4 o’clock. I wake up, disturbed from my sleep. I write down that particular line or image. Sometimes it makes sense and sometimes it doesn’t. When I look at it in the morning, sometimes I might have forgotten what it was all about. It may never get written. But very often, it gets written. I remember how it came to me. Then, that line multiplies and develops into a whole poem. That’s how it mostly happens. I have never written a poem because somebody has asked me to write a poem on a particular theme or something else. I have always said that this is not the kind of thing that I can do. That’s why I have never written film songs. Many have approached me to write film songs because I have a fine sense of rhythm and I love music. But then you have to write something suiting that particular context in the film which is something I don’t want to do. Maybe, if I try, I will be able to do it. But it is something I don’t want to do. But there are actual events that sometimes prompt you, and push you into writing, especially cruelty and violence. Bertolt Brecht had said that there are joys in life but it is always the sorrows that push me to the writing table. I think this is true for most poets. And this is certainly true about me. When something very sad happens in my neighborhood, or maybe in my country, or maybe in the world, sometimes I feel like responding to that. This response may come out as an article because I sometimes write socio-political essays other than literary critical essays. But sometimes it comes out as a poem. Of course, I try to see that it is not very loud and it is not a very direct reaction to the event even though there may be references to that, even oblique references, for that matter. These are some of the different ways in which poetry comes to me. So, I can only speak of one poem and how it came to me, not about all my poems and how it all came to me.

Sometimes it may be a landscape that stares at me. A poem about Shillong was conceived when I was coming back from Shillong. Sometimes, these things burst into poetry. A character you have forgotten, or something you have read in another poem, or some myth, or some legend- these burst into poetry unexpectedly. I never knew that Banalata Sen was going to come in that particular poem. That’s how poetry surprises the poet himself/herself.

Aritra: What is your favorite time of the day for writing?

Satchidanandan: It is generally early morning or late night. By late night, I don’t mean very late but maybe after 10 o’clock which means that I need a bit of quiet atmosphere when people are generally sleeping and there isn’t much noise around to disturb my concentration. It’s not that I write a poem every evening or every day. But when I write a poem, it is generally during the early morning hours or late evening hours. But I may do some revisions later. Even now, I am an old-fashioned poet in a sense because I have to have a pen in hand and write my first draft on paper. Then, I copy it onto the laptop and do the revisions there. It’s just a habit. The next generation may not find it very necessary to do that. They can write the first draft directly on the computer. But I can’t do that because we are people who were introduced to the laptop culture much later. So, I still need a pen and paper to write on.

Aritra: It has its own beauty because you are striking off a line and then you are stepping on it.

Satchidanandan: Yes, I strike off lines, I strike off words, I revise lines. Sometimes I strike off an entire stanza. These processes take place while I write. That’s what I call a first draft, the one that happens after all these. I copy this first draft onto the laptop. And later, there are mostly minor revisions that I do on the laptop. Then, I finalize it. But even then, I keep all the drafts with me because sometimes you want to go back to them. You feel that a line you had written earlier or a word or image that you had used earlier was much better than what you’ve written later. So, you may want to go back. In the beginning, I did not have such thoughts because of which I lost lines and images. But now, I am particular. I keep all the drafts in a file. I can go back to that line that I had removed but later I found that it strengthens the experience of the poem.

Aritra: I feel like we are paying tributes to the hurdles we face during the process of writing.

Satchidanandan: Yes, yes, exactly!

Aritra: Every single book by you in English translation contains poems written in different phases of your career. For instance, He Walked with Time opens with the poem, Granny, written in 1976. The following poem, Disquiet: Autobiography: Canto One, is written in 2000. Statuary, the first poem of Rain over the Coffin is dated 1972, while the next poem in the book, The Knife Thrower is composed in 2006. Can we assume that while making the English manuscripts you are revisiting your oeuvre and taking a look at it from a vantage point and that your idea of a book in Malayalam is not replicating itself when you are making a book in English? How does the idea change when you shift from Malayalam to English? First of all, we will like to know your idea for a book of poems.

Satchidanandan: In Malayalam, as soon as I have enough poems for a book, I go for publishing. The publishers keep watching and I get letters from at least two or three major publishers who let me know that now I have enough for a book and I should give them the book. This is how most of my books have come to be. Except during the early days. But even then, I did not have to ask any publisher. A publisher came to me and said that they think that it is time for me to publish a book.

In Malayalam, I have many selections done by myself or by other poets- younger poets or poets of my own generation. There are several selections like that. There is even a selection of poems done by a film actor who was a younger friend of mine. He was a great reader of poetry. His name is Joy Mathew. He is now a very established actor in the Malayalam film industry. He has made a selection of my poems which he likes. Also, Balachandran Chullikkad who is a poet of the next generation has made a selection of my poems which have been published. Then, I made a selection of my poems after a particular period. Now, I have a big collection of poems in Malayalam, from 1965 to 2015. Those poems are arranged chronologically. Before that, my poems were published in three volumes thematically. It was edited by a young friend, Rizio Raj, who was also a researcher. She wanted to go by themes even though it becomes very hard to define the theme of a particular poem. But she said that there are several poems of mine that can be clubbed as ecological poems that have something to do with the environment and nature. Then, there are love poems, there are family poems, and there are poems about the social events that are happening at a particular time. So, she arranged my poems in three volumes depending on what she thought were the themes of my poems. It was a thematic arrangement. The poems in each section are arranged chronologically. But when you go to another section, you will find some poems of the same year being repeated there. In Malayalam, all ways of organizing the poems have been tried.

Generally, when I have a new book, it is a new book. In two or three years, I generally have a book. In Malayalam, poetry books are generally slim, containing 100 pages or 120 pages. That’s what the readers seem to like as well. So, when the publisher thinks that I have enough poems, I look at them and revise them. Sometimes I dismiss some of the poems that I do not want to publish as part of a collection. If you look at all my individual books in Malayalam, there is a chronology because these are poems written during the three years prior to the publication. And also, there is a big anthology of about 1000 pages where my poems are arranged chronologically, year by year.

In English, this is not the case because I don’t have all my poems in English. So, I want to create some kind of arrangement when I publish my poems in English. In The Missing Rib, you will find that the sections may have some kind of a thematic orientation. As I have already said that reducing a poem to a single theme is obviously a simplification but generally, the poems are about nature. It is the foregrounding of a theme. That is all I can say. I cannot say that all the poems are of that particular theme because several themes come into each poem- love, nature; many themes coalesce in a single poem. But then you read a poem and think that ‘okay, this looks like a love poem’, or ‘this looks like a poem about nature.’ So, in The Missing Rib, you will find that kind of arrangement. Not exactly chronological but somewhat thematic just like what my friend, Rizio Raj did.

When you come to the Harper Collins anthology While I Write or the Sahitya Akademi anthology The Misplaced Objects (the translation of the book which got the Akademi award), you see, in these books, I have a selection. It’s not arranged in exact chronology. But there is a kind of development from one poem to the other. I am not sure whether every reader will follow my way of thinking and understand those developments. But what I think is a kind of gradual development of my poetry both in form and in outlook. There are different ways of arranging poetry. I have tried different ways to arrange my poetry and others have tried their ways too.

Aritra: Can your famous poem Gandhi and Poetry be read as a bridge between Gandhian and Wordsworthian ideologies? Does it not also effortlessly use the tropes of progressive literature?

Satchidanandan: Yes. It also sums up the history of poetry in a way. You know, there was a time when we used to think of Kalidasa as one of the stars of Vikramaditya’s reign.

Aritra: Also, you have to reject Sanskrit as an official language.

Satchidanandan: Yes, and use the language of the people. That’s also typical Malayalam usage. Not that I hate Sanskrit. I do read a lot of Sanskrit. But Sanskrit has always been looked upon as a symbol of sublimity and height and ultimately, it also becomes a symbol of Brahmanical power. That is why in my poem, Gandhi asks us to speak in the simple language of the people. If Gandhi ever wrote something about poetry, it would perhaps be along these lines. That’s how I imagined it to be even though he never said anything about poetry. I believe that his very life was deeply poetic with all his changes, confessions, and re-thinking which are all parts of the making of a poem. In Gandhi and Poetry, there is the history of poetry in the poem and there is a new understanding of poetry, its language, and its message.

Aritra: You along with Tomas Tranströmer took part in a poetry reading session to commemorate the victims of the Bhopal Gas tragedy in 1984. If we talk about the social involvement of a poet, this is by far the best example of that. For a poet, poetry itself is the best way to be involved in life. Has the world changed with the advent of social media?

Satchidanandan: The world has changed but I cannot say whether it is for the better or for the worse. Just like all human inventions, social media too can be used to create an atmosphere of hatred or to empower people and create a new harmony among the people. I am not yet sure about the direction that social media is taking. I do closely watch social media. I use it too. I am on Facebook and once in a while, I use Twitter and other social media platforms as well. And when I watch it, I notice that a lot is happening on Facebook; often, it is very nonsensical. Even if we make a very important statement, the reactions often trivialize what one is trying to say. Once in a while, you may find something meaningful which teaches you something. But it is very rare. Again, there are paid armies of the right-wing who attack people and some of the state government policies. I am also told that there is some form of robotic intervention for these trolls. It is not necessarily done by human beings. There are also people who are paid to keep a watch on the media and they keep abusing people who criticize the government or its policies. They don’t know how to react intellectually, so they keep abusing the dissenters. There’s a lot of hatred out there. So, that’s what really frightens me.

It could be used as a platform for creating harmony and unity among people. But very often, it is used to further the cause of hatred which is already vicious and reaching its extreme point in the country. Like other inventions, for example, atomic power- it can be used for good; it can be used for evil. This is true about social media too.

And of course, it also has its own literature because there are a lot of poets who write on Facebook or they have blogs. I believe that there is some good writing going on there because I was the first to edit a collection of blog poetry in Malayalam. It was more than ten years back when blogs were just coming into existence. Many Malayalam poets, especially those living outside Kerala, had their own blogs. Our most important publisher, DC Books, asked me to think of a collection of these poems. I agreed, in a moment of weakness. I had to read a lot. I publicized it on my Facebook and I began to get a lot of links for various blogs. I went through 6000 poems at that point in time. Now, the numbers must have increased. I chose only 60 poems of the 6000 poems. So, this was the proportion of good poetry to bad poetry that was/is happening on social media.

I am not against poets using social media for poetry at all. I am not against any kind of writing that way. But everyone has one’s own standards of measuring, understanding, or evaluating poetry. I found 60 poems and I collected them. I called the book The Fourth Space. Perhaps, you will know about Homi Bhaba’s use of the phrase ‘third space’ for the diasporic space because they are not from the place from where they came and they have not reached the place to which they belong. They do not belong to both these places and therefore, ‘third space’. So, I thought that this virtual space could be the ‘fourth space’ where you are there but you are also not there! You could play with it. You could use other names and do mischiefs there. So, it is a very strange kind of space. It could be used for good; it could be used for bad. But I am afraid that it is more often being used for spreading hatred than for creating real bonding among the people. This scares me and this really worries me a lot.

Aritra: In your poem, The Indian Poet we see a profile of the poet being built with several historical, mythical references rooted in the vast canvas of our culture. In the poem, the poet is a god with three faces. Are they actually three separate entities with three different identities accepting to inhabit one common body? Because, someone is an ‘Indian poet/ writer’ only outside the country; inside, he or she is either a ‘Marathi poet’, or a ‘Tamil poet’ or an ‘Assamese poet’ etc. Your essay, The Plural and the Singular points out the adverse effect of the ‘traditionalization of the social order,’ which blindly follows the colonial knowledge, omitting the indigenous discourses. To deal with the problem, you said, we need ‘a fresh literary cartography.’ How far are we today from achieving the goal?

Satchidanandan: I think there is an awareness that is slowly dawning, especially on students, teachers, and scholars of comparative literature that we need to take into account the differences among our literary cultures, at least as much as the similarities. I don’t deny that there are certain things that are common even though it is a little abstract to think about an Indian experience. Similarly, it is also abstract when you think about Indian literature in a singular sense. The more I think of it, the more I am drawn to speak about the plural. So, I am coming closer to what Nihar Ranjan Roy said that ultimately, literature belongs to a language even though it may travel to other languages, hence, it becomes very important to take into account the differences; differences in regional cultures; differences in the ways in which each language works; differences of the personal and social backgrounds of the writers. I want to emphasize them because there is a forced attempt to speak of a single India with a single religion, a single race, and even a single language. These are times when we need to emphasize our plurality. Not to divide India. In fact, it has never divided India because we have always been plural. We do not have singulars! We have eight Upanishads and we have thousands of gods! If you think of it, you don’t have singles. We always have two or more. That has not divided the country. Emphasizing the plural will not divide the country. It is only to say that we are diverse but still, we stand together!

Aritra: You once quoted U.R Anandamurthy when you said, “If you look at the diversity in the Indian literature, you sense a unity and if you look for unity, you sense the diversity.” [In the book titled Positions: Essays on Indian Literature]

Satchidanandan: Yes. I thought that it was a dialectical statement. It really happens to all of us. For example, while translating the Bhakti poems, they are supposed to belong to a single movement. But when you closely read Kabir, Tukaram, or Bulleh Shah, you also feel how different they are. It is true that they are connected by some abstract spiritual understanding of the universe. But the forms they use, the languages they use, the gods they worshipped, and the ways in which they try to understand Indian tradition and philosophy; you also find a lot of differences between them. It is in retrospect that we call it the Bhakti movement or the Sufi movement. But if you really look at each of them separately, they were also very different. And this is true for other movements as well. This also has connections to my work in Shimla where I was made a national fellow at the IIAS, where I was looking at this plurality in movements. For example, in the progressive movement as well. The progressive movement happened in Urdu, Malayalam, Tamil, and many other languages. But if you actually look at the works, you will find different kinds of influences, different ways of using language, and different communities being represented. What we know as movements are often called so in retrospect. When actually the writers were writing, they were not necessarily aware that they were taking part in a movement. It is very true for the Bhakti movement because it starts somewhere in Tamil in the 4th and 5th centuries. That’s where it begins with the Shaivite and the Vaishnavite movements in Tamil. Then, it goes forward and spreads to other languages in India. If you look at all of them, you will find that each poet was different and each had his/her own way of looking at life, way of looking at spirituality, and way of worshipping God.

Aritra: What are you reading currently? Any recommendations?

Satchidanandan: There are several things that I read together. I have been reading Romila Thapar’s book Voices of Dissent: An Essay. It came out quite a while back but I did not get time to read it. And I am also reading the poems by Maram Al Massri whom I happened to meet at the Madelaine Literary Festival. It’s a translation from Arabic by a woman poet who is very fascinating. I always keep reading a book of poems, a work of fiction, and something academic. I was reading some very interesting Malayalam novels too. One is a shuffle novel that has just come out. In Europe, there are five or six novels like that where you have cards. These cards are put in a box and given to you. You can organize them in any fashion and you will get different stories.

Aritra: Like Hopscotch by Julio Cortazár.

Satchidanandan: Yes, it is something like that. Herta Müller has one. So, this shuffle novel that I was reading was about Travancore, the southern part of Kerala which was a state some time back. So, when you organize the cards in different ways, you get different histories of Travancore. That is one novel that fascinated me. There was another novel called August ‘17. Again, it’s a recreation of history. It’s an imagined history. Here again, Travancore comes in. This writer imagines that if the history had been different; if instead of Indian independence, Travancore had declared itself an independent country, then what would have happened? He imagines that kind of history— India as a different country and Travancore as a different country. He imagines the kind of troubles going on— post-independent India trying to annex Travancore and there is resistance to it; finally, Travancore wins. This is a completely imagined history which has its problems but it is absolutely fascinating! Because I think this kind of realism has almost disappeared from Malayalam short stories and novels. Mostly, some element of play or element of magic has come into fiction and it was already there in poetry. I keep reading these three kinds of literature, simultaneously. Whenever I feel like relaxing, I read.

Aritra: What is your advice for young poets?

Satchidanandan: It’s a piece of advice that I keep repeating. The piece of advice was given by Nicanor Parra, the great Chilean poet, who said, “Write in any way you like. So much blood has flowed under the bridge. Only one condition: you must advance on the blank page.” I keep repeating this advice whenever I speak to you, or other poets. Finding your page is the most difficult challenge that young poet faces; finding something that others have not written about, or finding something that you can write in a different way from what others have done before. That is the point: to find your location; where are you located in the history of world poetry, in the history of the poetry of your language, and in social history? Finding your location; finding your own page, and then advancing on that blank page rather than imitating somebody or repeating somebody even if he/she is great. So, advance on the blank page!

0 Comments