Translated from the Bengali by Sraman Sircar

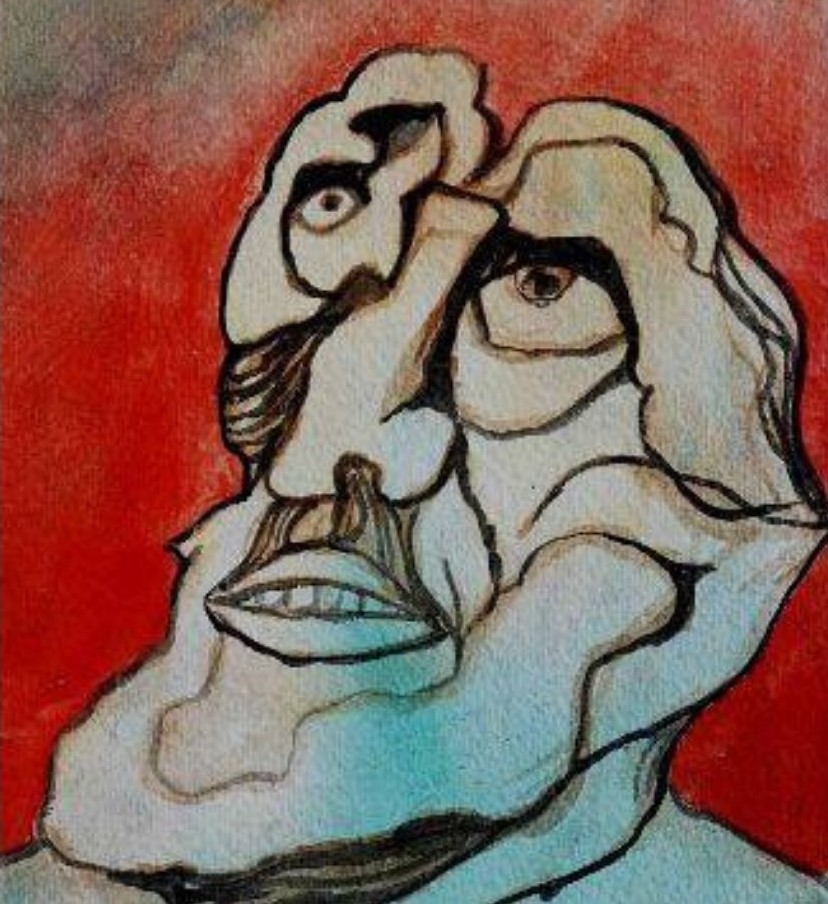

A painting by Anil Karanjai, one of the luminaries of the Hungryalist movement.

3

I used to live with my extended family in the Bakarganj locality of Patna till 1954. Our neighborhood was surrounded by slums and rife with crime. Since early morning, people would jostle and argue to fill up water at the taps on the road. We played with our spinning tops in the various alleys, along with footballs made of newspapers. There was no electricity. While studying at night, my sisters often trapped cockroaches against the glass shade of our lamp. Outside, the midnight gambling sessions ended either in vicious knife fights or with the ruckus of cheap alcohol and traditional drums. Amidst the din, my paternal uncle would occasionally play his clarinet. I attended a school called Ram Mohan Roy Seminary that was run by the Brahmo Samaj. After we moved to the house built by my father in the Dariyapur area of the city, I spent my youth in solitude. Reading books and goofing around with friends. Running away from home. Writing poems. I realized that mainstream Bengali literature was entirely detached from my everyday reality. By then, I had devoured every bit of information about the Imagist, Symbolist, Surrealist, Dadaist, and Futurist movements in the West. A new movement was now needed to make the Bengali language cast off its old skin. But Patna wasn’t the place where you could do so.

The little magazine called Chhoto Golpo, with Lal Mohan Das as its editor, helped me to find the name and address of a brand-new poet: Haradhan Dhara. I instinctively realized that such a name would have a refreshingly new impact on my movement. After corresponding with him, I turned up at his home in Howrah—a humble mud house with a thatched roof located in a dirty, dark alley that had emerged out of the Netaji Shubash Road. There were ten to twelve rooms directly adjacent to one another. Out of them, Haradhan resided in two with his mother, father, and brother, while the rest were occupied by other tenants. One of their rooms had a giant bed right beside a window with wooden grills. On it were placed piles of papers and magazines so tall that they had reached the roof. Manik Bandyopadhyay graced the small shelf on the wall. There weren’t too many books otherwise, but innumerable magazines. The veranda had an enormous mound of freshly collected pumpkin seeds and snails. Meanwhile, there was a pond outside that had just a pit toilet on its banks with a jute curtain instead of a door. A mug had been placed on its steps and I could hear someone cough behind the curtain. After glancing through his papers, I realized that Haradhan was a virgin reader who hadn’t corrupted himself like me by reading Western classics.

—My name is Debi Roy.

—I’ve come to meet Haradhan Dhara, please tell him I’m Malay Roychoudhury from Patna.

—I know. I am Haradhan.

—But then…?

—I’ve changed my name through an affidavit. Didn’t like the old one.

It dawned on me that this lean, slender young man had donned a cloak of romanticism. Despite living in a hovel, this name had let him immerse himself in a lyrical, poetic quality. And Debi Roy could speak endlessly—joy, fury, hatred, envy, and ambition all came tumbling out of him one after the other.

—Why Debi Roy though? Isn’t it a bit effeminate? There can be so many other names.

—No! I’m creating myself against the backdrop of Debi Singha and Sitangshu Roy from the era of the Great Famine.

I told Debi Roy the details of my movement, but he didn’t seem to have much faith in it. He was especially unconvinced by my idea of publishing our poems on small strips of paper in the form of handbills rather than an actual magazine. “They can’t be kept in stalls for sale, and everyone in the Coffee House would laugh at us. People would give our handbills a brief glance and then throw them away like crumpled scraps of advertisement. They would think we’re trying to sell toothpaste or pills for increasing semen!” Despite all these objections from Debi, I was adamant that our poems would come out as handbills, and if required, they would be published weekly or monthly on bills of various sizes and colors, but the magazine format wouldn’t be adopted for now. We decided I would be publishing them in Patna and addressing the correspondence from our readers, while Debi’s address would be shared on the bills, and he would also help acquire more partners and poems for our venture. Right from the very beginning, we had made up our mind to relinquish all sorts of elitism in our quest. After finalizing the details with Debi, I traveled to Chaibasa via Jamshedpur to meet my elder brother Samir Roychoudhury. He assured me that he would discuss my movement with Tanmoy Dutta, another poet with fire in his belly, and with that, I returned to Patna.

But as soon as I had submitted the manuscript of our bulletin to Tapan Printing Press, all hell broke loose! “What in the world is this?! I can’t publish all this hungry nonsense! Which political party have you started working for these days?” I couldn’t publish it anywhere. There were always different excuses. Fear of politics. Fear of subversion. Fear of obscenity. Always one fear or another. I decided that our bulletin would come out in English. There was a job press close to my home that was in the business of stamping the lids of boxes of sweets, and that’s the place where I was finally able to publish our bulletin on art paper. It was the first cry of the Hungry Movement that shed light on why the word hungry was so relevant, what we wished to accomplish and our reasons for it, and ultimately, why there was a hungry time. I packed the bulletins in one of the boxes of sweets from the job press and parcelled it to Debi Roy.

A few days later, in November 1961, my brother arrived in Patna accompanied by a bearded, bespectacled man with rough hair and clad in a dhoti and shirt. Shakti Chattopadhyay. I had read a few of his poems. He had a new idealism and was eager to incorporate colloquial terms into his poetry. Unlike the lexicographical poems of the 1930s, his work had the courage to showcase the language of the lower classes. Back then, I was addicted to drinking toddy in the evenings and sometimes arrack in the afternoons. That’s why when I saw Shakti Chattopadhyay lighting up reefers one after the other, with his mouth reeking of country liquor, I thought him to be an acceptable personality. We discussed the details of the Hungry Movement and he seemed to be quite enthusiastic. At the Patna station, we had further conversations strategizing about it.

I wrote to Debi about Shakti Chattopadhyay and sent him some money in the hope that it could be used to procure writings worth publishing. Once again, I came out with a bulletin in English where this time we wrote—Creator Malay Roychoudhury, Leader Shakti Chattopadhyay, Editor Debi Roy. After returning to Kolkata, Shakti wrote A Proposal for Poems in the Samprati magazine. It was the first time the Hungry Movement had been discussed in any journal. He had written, “The main objective of this movement is to be all—devouring.” Debi Roy’s frequent postcards began to convey to me the news of the tremendous excitement generated by this movement in Kolkata. More news kept on arriving—Sandipan Chattopadhyay, Binoy Majumdar, and Utpal Kumar Basu had joined the movement. Basudeb Dasgupta had taken part too. Pradip Choudhuri from Shantiniketan wanted to publish poems as well.

Every month I began sending money to Debi. In April 1961, I had got a clerical job at the Reserve Bank that paid me hundred and seventy rupees. I had to sign my name on feudal bonds all day long, and within just a few months, it had totally improved my handwriting. Subimal Basak was also working in Patna at the time. On hearing the news of the movement, he came to inform me that he was getting his job transferred to Kolkata. I asked him to get in touch with Debi. Subimal’s father used to be a renowned goldsmith in Patna. But his gambling addiction eventually drove him to commit suicide by drinking nitric acid. After his death, the house where Subimal and his family used to reside gradually turned into just the bare bones of an edifice. The windows lacked both grills and frames. There were no doors as well. The entire house simply used to stand wide open on the road.

Both Debi and Subimal’s letters conveyed the news of the tumultuous agitation in Kolkata. Several people in the Coffee House were shredding and throwing our bulletins away as soon as receiving them. Debi was warned to stop all of it if he did not wish to be thrashed en masse. A group of authors threatened to torture Subimal by stabbing the underside of his nails with pins. But all these threats only further bolstered their confidence in themselves. I was still in Patna. Meanwhile, whenever either of them would set foot inside the College Street Coffee House, catcalls, taunts, and jeers would be hurled from the other tables. In the afternoons, the young students of the Presidency College would descend upon the café to gawk at them.

4

On 17 July 1964, troublesome news came out in the Dainik Jugantar newspaper with the colorful headline—’Roguery in Literature’. This was what it had to say:

“The true place of the politician in modern society is somewhere between the corpse of a prostitute and the tail of a donkey—such is the proclamation of a group that introduces itself as a literary association. But this group has a political nature too, and the aforementioned statement is one of the best examples of its political objectives. Its declaration regarding poetry, however, is even more startling—the poetry book is more durable and delightful than a wife. A married woman turns into the overly soft cover of an old book within a few days, but poetry is the lady who day by day exerts a firm grip on oneself!

Two years ago, the youth of Kolkata had displayed the excessive audacity of starting this movement by dismissing not only the police but also all sorts of parental, social, and literary propriety, and they describe themselves as the Hungry Generation. In terms of its following, this movement has attracted at least fifty young men from Kolkata over the past couple of years. Their age ranges from 18 to 32. Among them, one can find people from various strata of society like students, professors, salaried individuals, etc. They often gather in the various restaurants and pubs of central Kolkata for their intellectual chats, at times even assembling on the street itself, and they don’t shy away from consuming cannabis and hash as well. Since they consider themselves intellectuals, they vehemently oppose being grouped together with those who call themselves the ‘Beatles’ after smoking weed beside the river Ganga, or those goons in dirty trousers and pointed shoes who are under constant surveillance by the police in different neighborhoods of the city.

However, like these two groups, the Hungry ones also dress and behave weirdly, and the police view them with equal suspicion. This group apparently has networks spanning the whole world. The photocopies of their bulletins can be found in the New York Public Library as well as the British Museum. A renowned publisher in London has decided to come out with a paperback collection of their poems. Their manifesto on poetry has been published in the City Lights journal of San Francisco. The Mexican journal El Corno Emplumado has come out with Spanish translations of their work. The angry ones from England and Europe have congratulated and corresponded with these Hungry ones. Who funds this movement? They say the money comes from a certain minister clad in a saree, the labor union of the Jharia coal mine, the Baruipur Exercise Club, the Jogmaya Club, a certain actress, an influential individual from Pakistan, and a certain secretary of the Hindu Mahasabha! Their main grievance is that their work never gets published in any mainstream literary journal. That’s why, one day they simply walked into the office of a newspaper, handed over piles of their papers, and demanded, “This is a story, you have to publish it!“ They have even sent their books in shoe boxes to be reviewed by critics!”

Merely two days later, an editorial by Amitabh Chaudhuri about the Hungry Movement was published in the same newspaper, and as expected, it too had a high–nosed opinion to share: “The hungry youth of Kolkata are crying foul, yet they are also getting trapped within their own self—condemnation; is this the repentance of unproductive politicians or the curse of a sick society?” The floodgates had opened by then and one after the other similar news began to come out in newspapers representing the whole gamut of the political spectrum. For instance, The Angels are so Awful (Chatushparna); What Sort of Useless Madness is This? (Darpan); Roguery in Literature: What is It and Why (Amrit); Perverted Sexual Greed in the Name of Poetry (Janata); Complaints against Creation of Obscene Books (Anandabazar); Erotic Lives and Loves of the Hungry Generation (Blitz); The Destitute Community (Jalsha). The Statesman and Dainik Basumati newspapers, on the other hand, chose to come up with cartoons.

Meanwhile, Tridib Mitra, Subimal Basak, and I decided to leave this tremendous excitement in Kolkata behind and travel to Digha. The district of Medinipur had been hit by massive floods. As a result, the tourists had fled and all the buses plying to Digha from Kharagpur had been canceled. But we flagged down the lone truck that was still on the road and it dropped us off in Digha at one in the morning. We directly headed to the beach. Rows of uprooted pine trees caressed by the waves were strewn on the sand. Streaks of lightning kept tearing apart the black clouds. There was no one around, except for the sound of the waves crashing on the shore. The three of us took off all our clothes on the beach and stayed completely naked in the sea from midnight till dawn. It felt as if invisible bells of air were ringing in our minds.

Upon returning to Uttarpara from Digha, my paternal grandmother handed over a letter for me that had arrived from abroad. Sunil Gangopadhyay had sent the following letter from the Iowa Poetry Workshop—

Dear Malay,

I’m unaware of all the ruckus you’ve created in Kolkata that you’ve boasted about in your letters. What have you been up to? A few of my friends did vaguely write to me about some of the troubles that have occurred in the Coffee House.

Instead of writing, I think you’re more interested in starting a movement and stirring up trouble. Do you get enough sleep at night? All this amounts to nothing and I’m not bothered by it at all. You can carry on with your movement; Bengali poetry will never care. I suspect you’re greedy for a short route to fame. Who knows, you might even get it. I, on the other hand, have never been in any movement because the passions of my heart have always kept me busy.

But to be honest, the city of Kolkata belongs to me. I’ll go back and set up my kingdom there, while all of you can’t do a single thing to change this. Several of my friends are already emperors. I would have feared you if I had noticed even an iota of charisma in you so far. Among those younger than me, only Tanmoy Dutta had entered the realm of Bengali poetry armed with a sword, and he was at least six years my junior. However, since the times of Jibanananda Das, there hasn’t been a more powerful poet in our land. Tanmoy sensed this and departed in a bout of envious fury, and that’s why I’m still remorseful on his behalf.

I haven’t written anything at all so far, I’ve just been preparing to write all this while, but unlike you, the thought of commercializing poetry has never come to my mind. Just like Balzac, I’ve created a separate vocabulary for my poetry and prose. No matter how much I’ve doted on you Malay, I haven’t really been able to muster up any enthusiasm for your poems to date. But of course, I’m still waiting for it to happen.

Many believe that if they can’t keep the subsequent, younger generation of poets under their sway, their literary fame will not last. That’s why a few of my friends had once become your patrons. I, however, don’t pay heed to any of this. I have enough strength in my feet to even stand alone. All that I’m trying to say is this—if you’re my friend, then you can be with me; if you write poems well, you can be with me. But the ones who are not my friends and write atrocious poems, they’ll be banished from my presence! I also find it particularly vulgar when someone raises the issue of having an age gap with me.

Keep on doing all that sanctimonious hypocrisy about movements or generations! I relish witnessing them or reading about them, but only from afar. I just can’t fathom why certain groups of people are so greedy that they’re eager to claim a hereditary right on the whole of literature! But let me tell you something. You must have noticed that I’m generally a peaceful, good–natured man. This is my true self, but the blood in my veins comes from east of the river Padma! That’s why you should ideally keep me at an arm’s length and not poke me too much. Otherwise, if I suddenly lose my temper, even I can’t say what I might end up doing! Throughout my life, I’ve been that enraged only a quarter of a single time, and that too just last year. I did not break up your Hungry Generation right at its very beginning only because I was feeling indulgent towards a handful of my friends who had taken part in it. However, keep in mind that I still retain the power to do so. But I’m not in the mood yet to destroy your playhouse!

One of my friends has informed me that you have published certain sections of some of my letters. I don’t write letters to call them literature; my letters are merely a collection of a few useful words. And obviously, I have nothing to hide. But if any of you publish my words after taking them out of context and inserting a few ellipses in between, then upon returning to India two and a half months from now, I’ll pull their ears and give them two hard slaps!

I hope you’re physically well. Accept my love.

The above has been excerpted from the book titled Hungry Kingbadanti: History of a Literary Revolution written by Malay Roy Choudhury, and first published in July 1994. This is the second in the series of writings from the book that will be published eventually on the magazine’s website. To read the first episode, click on the following link:

Keep a lookout for the upcoming episodes!

Also, read a bunch of Ewe poems written by Koukovi Dzifa Galley, self-translated into English by the author, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments