Translated from the Bengali by Rinita Roy

Never in our wildest dreams did we think Topu would ever come back to us again! Yet, he has come back amidst us. It startled and shocked us to no end that this is indeed the same person we saw for the last time near the High Court turning. We were positive we would never see him again! But he has returned! He has come back to us by some inexplicable and coincidental twist of fate! His return has left us all highly traumatized and flabbergasted. We are unable to sleep at night. Even if we are on the verge of dozing off, we are rudely jolted back into a state of shocked wakefulness. In the dark when my eyes alight on him, my hands and feet start to tremble, my body shrivels and shrinks under the quilts caught in the throes of a violent agitation.

In the daytime many of us gather here in our room and confer together in deep bewilderment, trying to make sense of this bizarre phenomenon.

During the day many arrive to scrutinize and assess the freakish coincidence. They wince at the sight of him, askance. Not that we are less confounded by the turn of events. There is bafflement in our eyes too. He spent two whole years with us. We were closely familiar with his breathing in and breathing out. Who would say that this is the same old Topu? What a bizarre incident this is! He is beyond recognition in his present state. If his mother is called to identify him, I am sure she will never be able to recognise him in his present state either.

And, how will she? From the group Rahat spoke out like a wise man, “If there were any marks of identification, then perhaps she might have been able. But in his present condition that is virtually impossible.” Having said that he let out a deep sigh.

We became a trifle distracted after this conversation.

After a day’s long and weary search we retrieved his address and sent Rahat on the errand to inform his family-his mother and wife about what had transpired here.

Rahat ran from pillar to post trying to locate them but returned empty-handed. He informed us that there was no trace of their whereabouts. We were left in a bit of a quandary as to what should be our next move. I looked up at Rahat for assistance.

He sat down on the bed with a thud and told us that all he could find out was that his mother had expired sometime in the intervening years.

Dead? How the old woman had rolled on the ground and wept for her son. I had also not been able to hold back my tears then.

“What about the wife?”

“Don’t talk about her. She has married someone else.”

“How could she bring herself to form a new attachment so soon after? Topu loved her dearly!” Nazeem muttered under his breath.

Shanu retorted, “What else was there for her to do? She cannot remain a widow forever.” Then he looked at Topu.

I shifted my eyes towards him too.

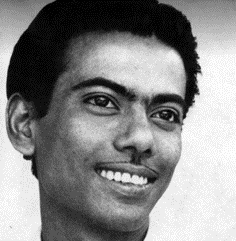

Really! Who would say that this was the same ever-smiling Topu? What a jovial chap he was! He used to laugh a great deal. He kept the atmosphere around him charged with his bonhomie and good cheer. Where has all that gone? Why am I filled with dread at the very sight of him now? Why does my blood curdle when I look upon him?

We were three great friends sharing a happy cameraderie!

Me, Topu and Rahat.

Topu was the youngest amongst us, but despite that he was the only one married.

A year after joining college he had married Renu. They were blood relations. She, a pretty young woman with a narrow waistline and a complexion like apple blossoms, would often come and visit him here. Whenever she came, we would collect some money and treat ourselves to tea and sweets. We loved those chatty, rollicking sessions. Topu was an ace storyteller. His sense of humour helped him spin yarns beyond compare.

Whenever he began a story no one was ever allowed to butt in. “Remember that man I mentioned to you, that big fat uncouth man whom I met at the Capital, that man who said he’d become a Bernard Shaw? Well, he died a few nights ago-came under the wheels of a ramshackle jalopy. And the girl who promised to marry him ran off with a foreigner the very next day. Runi knew the girl… Oh, you don’t remember Runi? She was once acclaimed to be the best dancer in town. Now, she is into politics. I met her the other day. She was thin as a rake before but now she looks rounded. She invited me to a restaurant. When she heard I was married she asked me what my wife looked like.”

“That’s enough! Now you can stop. Oooff, once you start talking there’s no end to it!” Rahat would say in his efforts to stop him.

Renu would admonish him, “You don’t say! There’s no stopping the flood once he starts.”

She would blush in embarrassment, and feigned resentment.

Yet there was no stopping Topu. He would put on one of his famous smiles and launch yet another of his funny nonsensical narratives, strewn with unrelated facts and irrelevant details. If we appeared indifferent or inattentive he would stop and add, “All right, since you do not want to listen to other peoples’ stories, then I’ll talk about myself!” He would go on, “I was thinking if I can pass the MBBS exam, I will not stay in this town. I will settle down in a remote village somewhere. I’ll have a small hutment there. You will see I will lead a spartan life, bereft of any luxury. My worldly possessions will consist of a small dispensary and nothing else.”

Topu would often wander off to a world of his dreams.

At one point in time he even wanted to join the Army.

But fate stood in the way. He was born with a congenital defect in his left limb. The two bones in his left leg were a couple of inches shorter than those of the right. But he acquired a pair of custom-made boots in which the left heel was lengthened to match the right. Because of the adjustment, his limp was not always discernible.

Ours was a rather humdrum existence.

We awoke with the birds! Topu was always the first to rise. He would awaken the two of us-“Come on get up! Can’t you see it’s morning already? Why are you two still sleeping like cattle, get up!” He would tug at the quilts covering our bodies and pull them off and awaken us. He would open the windows and exhort us to enjoy the sweet sunshine outside. “Don’t sleep any more. Get up!”

After waking us up he would make tea for all of us as a daily ritual.

Having savoured the cups of tea we would sit down to study. Around ten o’clock we would start for our classes duly bathed and sated with breakfast.

The evenings were spent in fun and frolic. Some days we went for rides. We often visited the banks of the Buriganga River. On the days when Renu accompanied us we would walk along Azimpura, and lose ourselves in the winding roads of the village.

Renu would often bring ‘dalmut’ for us. We would munch the snack as we walked along the village paths. Topu would say, “You know what I think?”

“What?”

“What if these long winding paths of red earth had no ending-they just kept rolling on and on eternally … Then we would have also walked on and on for all eternity.”

Rahat would frown and ask-“And since when have you started nurturing poetic sensibilities?”

“No, no, not at all… do I need to be a poet to have thoughts like that?” Topu would murmur hesitantly, “but still I get this strange feeling.”

His mystical poetic eyes would seem to brim over with dreams.

We were three good friends.

Myself, Topu and Rahat!

Our days thus passed by happily enough. But suddenly one day things came to a grinding halt. On the green lawns just outside our hostel premises a huge crowd had gathered on that fateful day. From very early in the morning an angry mob had assembled there carrying portable loudspeakers to shout slogans. Some even carried long poles on which they hung some blood- stained shirts. They pointed to the clothes fiercely with their index fingers and spoke amongst themselves, their angst visible and palpable.

Topu pulled me by the hand and said to me, “Come, let’s go!”

I asked, “Where to?”

“Why, to join them!”

I looked out and found the sea of humanity had started to move slowly.

“Come, let’s go!”

We moved forward towards the procession and joined in.

After a while we looked back and found Renu running towards us panting heavily. Just as I thought, she held Topu’s hand in a grip and asked, “Where do you think you are going? Let’s go home at once”.

“Are you mad?” Topu protested as he disengaged himself from her hold. He then added, “Why don’t you come along too?”

“No, I will not come! You come home with me.” She took hold of his hand again.

“What rubbish are you talking about?” Rahat was visibly annoyed. “If you want to go home, please go. He won’t!” Renu turned her face towards Rahat and glanced at him in angry desperation. Then in a tearful voice pleaded, “Please have pity on us, let’s go home! Ma is besides herself with crying”.

“I told you already, I cannot go now.” He released his hand again from Renu’s.

I felt a twinge of pity seeing the expression on Renu’s face. I said, “Why are you so worried? There is nothing to be afraid of. Nothing will happen. Please go home.”

She hesitated for a while, tears flowed freely from her eyes as she turned around and left us.

The procession had at that point of time crossed the Medical College gates and was approaching Curzon Hall.

The three of us were walking side by side.

Rahat was shouting slogans.

And Topu was carrying an enormous placard with the boldly written words, “We demand Bengali as our Official Language!”.

As soon as we reached the High Court turning, all of a sudden the people in the crowd started screaming and shouting, it seemed as if all hell had broken loose. There was mayhem all around. The crowd broke up and ran helter-skelter in all directions possible. Before we could fathom what caused the chaotic disruption, we found Topu lying on the ground. Blood oozed profusely from a large hole in his forehead -the placard still clutched in his hands.

“Topu………!!!” Rahat screamed aghast.

I stood immobile as if rooted to the ground-too stunned to move.

All at once two military soldiers appeared from nowhere, ran towards Topu’s body and in an instant carried it away before our very eyes. It happened so fast. We remained in shock, unable to move or stop them. My body had gone into an icy shock wave and rendered me frozen. But I recovered just in time and shouted, “Run! Rahat … run!”

“Where to?” Rahat asked looking at me in utter bewilderment. We ran with all our might to the University building.

That night Topu’s mother came to us. She was inconsolable and cried her heart out. Renu came too. There was no stopping her tears, which flowed on incessantly. She ignored us totally. She neither looked at us nor spoke to us. Rahat whispered his deep regret in my ears, “I should have been in Topu’s place. I should have died, not Topu.” What a bizarre incident it was! All three of us were walking side by side, nothing happened to us but a bullet had to find its way into Topu’s forehead! It was bizarre indeed!

Four years have passed since. That Topu would return to us was beyond our wildest dreams!

After Topu’s passing, Renu had come one day to take away his belongings. His worldly possessions consisted of two suitcases, a steel trunk in which he kept his books, and a bedding roll. Renu’s unsmiling face wore the same sombre expression.

She did not speak to us. Only once she addressed Rahat and enquired about his coat. Where was it she wanted to know.

“Oh! It’s in my suitcase.” Gently, Rahat extricated it from the suitcase and handed it over to Renu.

For a few days following the evacuation, Topu’s seat remained unoccupied. Some days in the wee hours of the morning we imagined a hand running over our bodies trying to shake us out of our slumber.

“Get out of bed! Don’t sleep any more. Get up!”

When we opened our eyes, we saw no one. But just looking at his vacant bed we would be engulfed in excruciating pain. Then a new student came to occupy Topu’s seat. He stayed with us for about three years.

Another boy came soon after. He was our new roommate. He was a congenial chap full of merriment and laughter.

On that particular day he was turning the pages of his anatomy textbook when he pulled out from under his bed a basket that contained a skeleton. He took the skull in his hands and started to examine it referring occasionally to the book open in front of him. All on a sudden he looked up at Rahat and asked him in a surprised tone of voice, “Rahat sahib! Please have a look here. Why does this skull have a hole in the forehead?”

“What’s that you said?” We both asked in consternation and looked towards him.

Rahat rushed forward and took the skull from his hands. He then bent over to examine it closely. Yes, there it was, a small round hole right in the middle of the forehead. He looked towards me-there was no mistaking the message that his eyes conveyed. I managed to mumble “His left leg bones were almost two inches shorter than the right”.

Before I could finish speaking, Rahat dived and reached for the bones in the basket under the bed. All the while his hands shook violently. After a while he cried out in consternation, – “The Tibia and the Fibula of the left leg are shorter than the right. Come and see for yourselves!”

I was shaking in great trepidation.

Rahat held the skull in his hands and tearfully managed to utter,- “Topu…………!”

He could say no more. His voice was choked by his tears.

Wonderful translation of such a moving story.

The Bengali language will live forever.