As an outlier, an inhabitant of the margins, the figure of Ashwatthama resembles that of a madman, naked and disheveled, groping for the shadows to protect his anonymity. His uncouth countenance paired with his inability to speak provoked an instant disgust among his listeners. As he tried to speak they mocked him, pelted him with stones until he fled and hid in the bushes. The sequence is not only unsettling for the portrayal of human intolerance and brutality but also questions human prejudices that affect their judgment. It evokes a profound question, “Would you recognize a god who wore the wrong body?” (Patil 13) Patil’s indictment is clearly hinted towards the unscrupulous crowd whose preoccupation with appearance failed to distinguish a sage from a madman. As a result, the only listeners that Ashwatthama gets are the Langda (the limping one) and the Bhainga (the one with squinted eyes) both ‘doms’, undertakers working day and night at the samsaan ghat disposing dead carcasses. The tale becomes more poignant as we realize the irony of the situation. All tales of bravery, courage, and grandeur finally boils down to a naught and pales into insignificance as death awaits everything. As readers we perceive that Mahabharata, apart from being the greatest of epics is also a tale that draws its magnanimity from the misfortunes and sufferings of the greatest heroes in Indian mythology. As a story that anticipates the Kurukshetra, the great battle which ends in an unhinged bloodbath, the setting of Patil’s narrative in the cremation ground is only but fitting—a grand tale of human achievements mingled with divine patterns sufficiently interrupted by scenes of death and loss.

Patil’s deeply symbolic vision paints the entire narrative within the punctuation of two big, inverted trees. The symbolism of the tree is multiple. At the very outset when we encounter the first tree it seems to represent the tree of life, standing tall from time immemorial, bearing witness to all the human actions. The symbolism of the tree is, however, further complicated as it is an inverted one and as the narration warns us against all our preconceptions, we realize that everyday mundane objectivity is not an ally to our tale at hand. The invertedness somehow prepares us for the maddening nature of the tale ahead, as Ashwatthama also asserts. We are thus initiated into the tale of vengeance of Dronacharya from King Drupad of Panchala, and their lifelong enmity. While narrating the events Ashwatthama points out the singularly peculiar situation as he recounts how king Drupad had sent his son to Drona for his lessons, as he trusted Drona’s capacity as a teacher and how Drona taught “his future assassin willingly and knowingly.” (Patil 36).

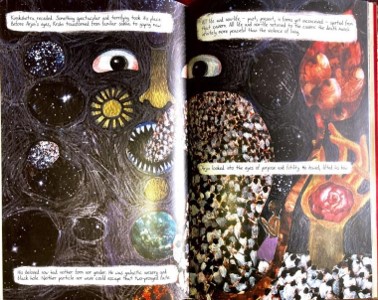

Sauptik majorly follows the main narrative of the Mahabharata comprising of the conflict between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, and the significant roles played by Krishna, Draupadi, Sakuni and others which finally leads to the battle of Kurukshetra. Patil uses a splash page to represent the battle. The color scheme and the figures strongly remind of the Ajanta cave paintings but the subject matter of the present panel effects an aesthetic juxtaposition which is probably an artistic decision made by Patil to mellow down the brutality of the war. Another very significant representation is the rendition of the Gita episode. Instead of following the known pattern of Krishna advising Arjun, Patil uses a splash page infused with blue and black to evoke the potent superhuman nature of the phenomena which is deeply impressionistic. The narrative closes with the inverted tree of life burning down thereby effecting a sense of closure. The sense of waste is unmistakable as we witness the severe carnage. However, the book ends on a note of hope for new beginnings as Ashwatthama achieves his long due peace.

0 Comments