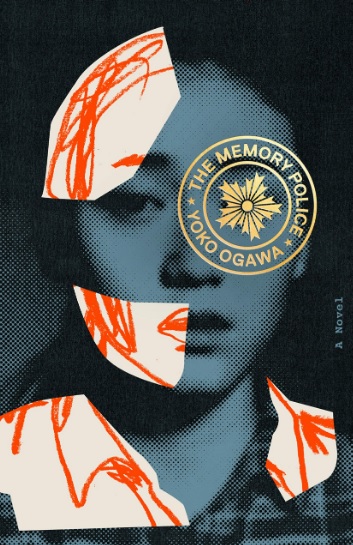

A Book Review Of The Memory Police: A Novel By Yōko Ogawa And Translated From The Japanese By Stephen Snyder

First published in Japan in 1994, and one of more than 40 works of fiction and non-fiction by Yōko Ogawa, The Memory Police is finely translated by Stephen Snyder, reaching English-language readers as if sent from the future. Stephen Snyder has, in recent years, earned a reputation for translating Japanese literature with its edgy, socially-conscious fiction with works such as Coin Locker Babies by Ryu Murakami, Out by Natsuo Kirino, and a finalist for the International Booker Prize The Memory Police being his crowning achievements. The novels have a common take on issues such as abandoned children, marginalized female factory workers, and the role of literature in oppressed societies. In the novel, he focuses on the fascism of the eponymous organization from which the novel derives its English name—The Memory Police. It is impossible to ignore the echoes of Nazi Germany and the treatment of Jewish people that Ogawa draws on, especially regarding the Memory Police themselves, and also the loaded imagery of the cramped, hidden enclave that the narrator builds within her home to hide her beloved editor who stands in for all things that she could not save. And those echoes are intentional.

It is a dreamlike dystopian story on an unnamed island that is suffering an epidemic of memory loss. In the novel, the psychological toll of this forgetting is rendered in physical reality: when objects disappear from memory, they disappear from real life. The disappearances range from mundane objects such as hats, or perfume, to natural beings such as roses and birds. Whenever something disappears, the residents lose all affective ties, memories, and even the understanding of whatever the object was. The disappearances over time take on an inevitability so much so that each subsequent disappearance garners little response from the islanders. Most residents accept the disappearance and discard the object, if possible, to continue with their lives. However, there are those like the unnamed narrator’s mother who can remember every forgotten object and are bound to suffer their remembrance against the general apathy of those who forget, and the state and its machinery, the Memory Police. Eventually, the narrator’s mother is taken away by the Memory Police too. The novel charts the narrator’s struggle against the disappearances and her desire to protect her editor, who can retain his memories like her mother, from the Memory Police as the island continues to fall into disarray.

Stephen Snyder’s translation of The Memory Police is resplendent yet there are moments when the reader is forced to ask: ‘how did it get here?’—the narrative is confused yet poetic at all times. Yōko Ogawa, following Japanese literary tradition, crafts a narrative from the mundaneness of life and casts it in the ethereal mold of existential symbols and speech devices which adds otherworldly serendipity to the narrative. Names of the characters and the protagonist remain a mystery for the readers with whole sections designed around abstract concepts of objects as they might exist in the subjective recollection of people as they go about their lives. These objects are defined as much by their past as their present. The unnamed narrator is a novelist who, having lost both her parents, lives a life of solitude and forgetfulness that is shared with the rest of the residents of her island. In the first half of the story, Ogawa paints a vivid yet oppressive picture of the unnamed narrator’s life as she goes about working with her beloved editor, R, on a gentle love story between a typist and her teacher that takes a nightmarish turn as the story progresses. The novelist has one other trusted friend, an old man whom she has known since childhood, who seems to embody all those the island has left behind in its relentless march towards an unknown and uncertain future.

Rather than situating the Memory Police as the true antagonist in the story, the novel instead points to the power of invisible historical processes and how human beings participate in historical revisionism. The Japanese title of the novel is Hisoyaka na Kesshō, which roughly translates to secret or quiet crystallization. Unlike the English title, the Japanese original does not focus on a specific group of bad actors but on a surreptitious, societal process underpinning the entire novel. As the novel progresses, it seems the Memory Police simply flow with the disappearances, using the situation to their political advantage. Initially, the disappearances are regrettable like the loss of harmonicas or the loss of several different types of food, but they generally seem harmless at first. With the smaller disappearances come increasingly troubling ones, objects that are a little more complex and abstract: photographs, maps, and books. Eventually, body parts begin to disappear making it evident that the disappearances have acclimatized and naturalized the islanders to the process of forgetting with devastating results.

To forget is to be disconnected from the past, making it easier to miss the connections that link events or people together in the present. Once a critical mass of information is lost, the linkages between them disappear. Although the islanders call them “disappearances”, the objects do not physically disappear but are destroyed or released. The disappearances are thus not a purely physical phenomenon but a mental and affective one. The narrator falls victim to the disappearances for the most part and finds it difficult to mentally grasp onto objects that have disappeared. But there are moments where hints of memory break through to her consciousness. There are no strong emotions or clear memories attached to these recollections, yet they are not entirely forgotten, instead, the memories ossify, and crystallize until the world becomes something naturalized and accepted.

Forgetting is twofold. On the one hand, the natural passage of time obscures the past, and oftentimes it is also a conscious decision. The disappearances on Ogawa’s fictional island may have started as a natural phenomenon, but at some point, the crystallization joined with human acceptance, gained momentum, and people came to accept it. Ogawa pulls no punches with how the novel pans out. While there is some hope, the consequences of generations of forgetting are entirely, painfully realized. Even characters, like the narrator, who try their best to push back against the forgetting, fall prey. The warning of the Memory Police is thus not to be wary of fascistic organizations that try to control the populace, but instead to be mindful of the invisible processes that are constantly occurring that allow such organizations to appear. For the islanders, disappearances are continual. For instance: one night, the inhabitants of the island feel a stirring, a realization that something is leaving. When morning arrives, they find that red petals are inundating the river. Some observe small ceremonies to mark the departure. Days later, as the rose gardens turn to desolation, the very word “rose” will dissolve from memory. Following this disappearance, the Memory Police conduct a thorough search for all images and writings about roses systematically to purge any remnants of their tangible and intangible existence from the island.

Ogawa’s weightless and unadorned prose weaves a world where memory is always associative: we remember not just the object itself but what it conjures. There are lessons for those caught up in accelerating times when life becomes a series of desperate calculations. There is an extraordinary moment when the novelist, living in a world from which birds have disappeared, has a sudden realization that “the arc of the last book as it tumbled through the air” looks like the wing of a bird. Ogawa’s narrative strategy is fraught with difficulties as her protagonist who is also a novelist cannot recall the disappeared things, and this obstacle gives her language, already reserved, a faintness—an almost translucent feeling. How thin the writing sometimes seems, even as it remains sure and fluid. As losses accumulate and we internalize the workings of this world, the novelist’s understated prose accrues a polyphonic power.

While a reader may feel the need to interpret it solely as a political novel, the book also reads as a profound meditation on dying. In its losses, we see the aching removal of a person from their world. In the twilight of life, memories weaken, friends disappear, and objects are lost. The Memory Police here may symbolize this continual process which marks the loss that eventually consumes each and every living thing. As the story arrives at its fruition, its power seems to come out of the thin air and thin existence in which its characters are trapped. Yet the force of its ending is cumulative and phenomenal and taps into the very source and meaning of memory. The Memory Police can be experienced both as a fable or an allegory, a warning and an illumination. It is a novel that reveals its ideas in layers, in inconspicuous ways, knowing that all moments of understanding and grace are fleeting.

Although The Memory Police have elements of Orwellian horror, Ogawa avoids purely political rhetoric by consistently presenting the underlying themes of the story with a calm, chilling understatement that will repeatedly catch the reader off guard. Here, as throughout the novel, Ogawa’s imagery is empowered by the beauty and simplicity of her prose, which in this elegant translation by Stephen Snyder, evokes a mood of elegiac sadness that blankets the twists and turns of the story and lingers long after the novel ends in inevitable dissolution.

For the reader, the inexplicable “laws of the island” are never explicitly revealed as Ogawa is using the machinery of the Memory Police to vivify a philosophical inquiry into the nature of self, the role of memory in its construction, and its inevitable dissolution as age erodes, denatures, and eventually destroys memories. The richness of characterization, the subtle poetic imagery, and the strangely compelling nature of the leisurely plot make The Memory Police singularly unforgettable. There are tropes and moments present that one might reasonably label Orwellian but at its center, The Memory Police is a story about what it means to be a writer and the impermanence of art, all masquerading as a dystopian fable.

Also, read the second part of a Bengali non-fiction, written by Shankar Lahiri, translated into English by Bishnupriya Chowdhuri, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments