NOTES ON TEHRAN FROM A PUBLISHING FELLOW

In Iran, wind is precious.

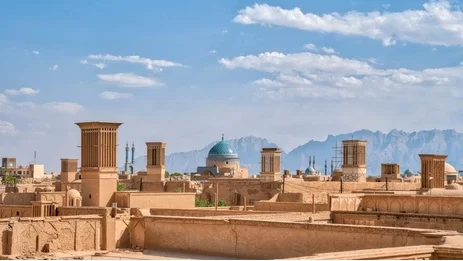

Even in ancient Persia, tall, austere towers were built specifically for capturing it. They rose like chimneys above other buildings, grinning with long slits that resembled rows of teeth. The so-called badgirs, or windcatchers. Air enters through the slits, cools down as it touches the masonry walls, then, heavier than warm air, it sinks and refreshes the rooms below, while the heat is expelled – just like smoke from a chimney.

The skyline of Yazd, an oasis between two deserts, is dotted with badgirs, but you’ll find them all over the country. Perhaps you can even spot them from above, as the plane glides gently toward Tehran, toward the airport named after Imam Khomeini. But to see them, you’d have to look. To look, you’d need to know they exist. And of Iran – apart from what the news, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and history books tell us – there is so much that, like wind, slips through our fingers.

When the plane touches down in Tehran, it’s nearly 6 AM and I’ve just opened my eyes. In the sling bag across my chest, the visa approval I received less than 24 hours earlier, with which I caught the first available flight so as not to miss the opening ceremony of the first Tehran International Publishing Fellowship the following morning. I haven’t yet realised that I’m visiting Iran. I had thought, of course, about the news, about the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a little bit about the history books too, but despite registering – for doubt’s sake more than out of prudence – on the dovesiamonelmondo portal[i], I hadn’t really thought about where in the world I was going to be. The landscape, I mean.

When I open my eyes, it’s almost 6 AM, and below me lies the desert. A dusty yellow expanse – sand, but also clay, the skeletons of unfinished buildings, and smog like a net across the sun. In my haste to get to the airport, I forgot to pack sunscreen. I wonder how hot the shamal is – the desert’s warm wind – before the windcatchers swallow it up. And then, suddenly, among the metallic clicks of unbuckled seat belts and the boring headrests, a flicker of colour catches my eyes. It’s not like I wasn’t expecting it. Quite the opposite. I’d read that there might have been an announcement, even, before landing, reminding passengers to bring their seats back in the upright position and women – Iranians or not – to cover their heads. But no such announcement came; maybe it depends on the airline, or the policy has changed. Still, what struck me weren’t the dark hair disappearing under the hijabs, the metallic clicks that release and the rustling of cotton and silk that traps.

Waking up at 6 AM in a place where there is nothing familiar for the eyes to rest on has this one advantage: before you can analyse or judge, you’re forced to simply see. And I would have loved to freeze time in that moment – to rewatch the swift, confident movement of the wrists, the fabrics billowing like sails. An obligation become routine, become elegance. All the women together – young or old, accompanied or not – wearing scarves and veils of every kind, united by a weary compliance and the unmistakable femininity of this gesture. Seemingly indifferent, easy. In truth, complex, showed off in its absurdity.

In my five days in Tehran, I never once managed to pull off that casual-chic look Iranian women have with the veil. I kept adjusting it, afraid it might slip, unsure if it was appropriate, or if I was being disrespectful. And when I took it off in front of the bathroom mirror, only to put it back on from scratch, I felt like I was revealing a mix of immodesty and clumsiness.

Until one time, from the mirror beside mine a girl whispered to my reflection, You shouldn’t be wearing this.

Because I am incompetent, I thought. But that you also sounded like at least you, or even we. That phrase echoed even louder on the final day of the fellowship, after the panels in which some of us fellows presented the publishing market of our respective countries. By then, we all seemed to know each other like old friends, united by books and a graceful curiosity for one another, inside the Grand Mosalla, that massive mosque they’ve been building for thirty years, destined to spoil before it’s even finished.

It came to me at lunchtime, as I sat with the brilliant interpreters. One of them, a girl, smiled half-heartedly as I adjusted my veil. I know, it’s stupid, she said.

Another one, a young man, told me he’d love to study in Italy but can’t leave the country until he completes military service.

While I had been worrying over a visa not immediately coming through.

Women, on the other hand, don’t have that restriction for travelling.

And I began to wonder, if I had to choose, which kind of freedom would I want?

And the word choice is anything but trivial.

Even the wind, after all, looks like freedom but is far from choice. It’s something you can’t resist.

It’s the first International Publishing Fellowship, but the 36th Tehran International Book Fair. Reading truly matters here. I get this feeling just from looking at the crowds, at the people approaching culture with such ease.

I’m at a publisher’s booth with Laura, a fellow from Brazil. We’re trying to spot publishing houses of contemporary Persian literature. I don’t read Farsi, and I find myself judging books by their covers, often beautiful.

As she hears that I’m Italian, a young girl turns to me and asks, What’s the theatre scene like in Italy?

The theatre scene.

She must have been 18. But she wasn’t pretentious, nerdy, or overly intellectual.

She was a drama student who wanted to know if Italians have a habit of going to the theatre, what shows go on stage, which ones are the most popular.

I smiled at my own surprise.

It’s not odd, in Iran, where culture – unlike in Italy, for instance – is not removed from everyday problems, but rather a shared language, tradition, daily bread.

So it’s not strange at all, for an 18-year-old, to seize the moment of a brief encounter to ask, What’s the theatre scene like in Italy? Because theatre, like literature, is a need, not a posture.

Then, we met Amir.

Amir, an editor and Japanese translator, as well as a student, also very young, could have brushed us off with a few words (I’ve attended and worked at enough book fairs to know how hectic it is to stay behind a stand). Instead, he invited us to sit with him.

First, though, he apologized: I don’t want to tell you what to do, or how to dress, but to come behind here, I have to ask you, please, to pull up your headscarves. Which we had let loose, like many young women around us.

At least my long sleeves hide the goosebumps when Amir begins reciting, and then translating, his favourite poems by Fazel Nazari.

I shivered as though a cold draft had swept through the hall – I blame Nazari’s verses, or the passion with which Amir spoke of the poetry, language and music of his country. Persian poetry and music, he explains, are linked, and a key element is tahrir, a rapid transition between distinct notes. A kind of vibrato, a shift between head voice and chest voice, from an Arabic word meaning both to write/to edit, because singing in a way rewrites poetry, giving it accents and emphasis, and liberation/emancipation.

In Iran, everything vibrates, it’s full of wind.

Which sometimes blows more forcefully, like that time a gust shook down the Translation Grant banner at the fair, right behind me during a meeting with an agent, and the interpreter simply sighed, That’s Iran.

I read that Mahsa Amini was supposed to be named Jina, which means life in Kurdish – in the sense of a person who gives life. But in 1999 Kurdish names were still banned in Iran. So at the registry office she was given the name Mahsa, which in Farsi means like the moon.

Like many Iranian women, Mahsa Amini wore the hijab only in certain circumstances, mainly outdoors or when entering public buildings, like schools. Or the booths of a book fair.

At Kurdish ceremonies or in volleyball games, she often let her long black hair flow freely in the wind.

That’s why her uncle – Safa Aeli, later sentenced to five years in jail for anti-regime propaganda – used to say to the rest of their family, Don’t call my girl Jina. Call her Shineh. Which, in Kurdish, means breeze.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] “WhereWeAreInTheWorld” is a service offered by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation that allows Italian citizens travelling abroad to voluntarily register their travel details. Thus, the Ministry’s crisis unit can locate and assist them in case of emergencies.

Also read, Jala’s Broken Teeth by Akhtar Mohiuddin, translated from Kashmiri by Nageen Rather, and published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments