A BOOK REVIEW BY ANANDI KAR

The Essential Stories, a collection of select short stories by two of the most salient short story writers from the time when the earliest clarion calls for modernity were being heard in Indian literature and translated by Muhammad Umar Memon and M. Asaduddin who are authorities on the respective oeuvres of these two writers, very ably delivers a flavour of what they are all about: their literary obsessions and stylistic distinctiveness. By conflating the works of these two contemporary litterateurs in a single volume, this Penguin edition aims to bring to the fore, the uncanny similarity in between Sadat Manto and Ismat Chughtai’s literary fates.

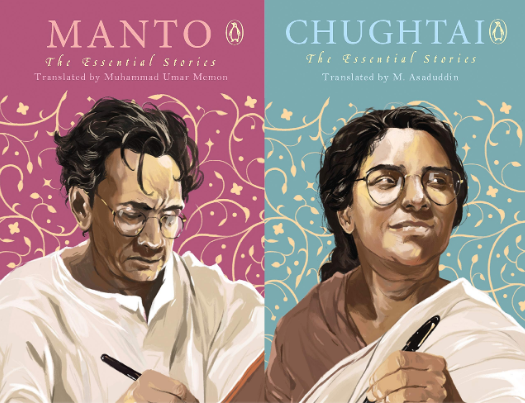

The most charming aspect of this book is the form in which it has been published. The book cover consists of the portraits of Manto and Chughtai, one on each side. One half of the book contains stories of Manto’s and the other half contains that of Chughtai’s; flipping one side would lead to the other’s contents. This arrangement makes way for almost a game-like, fun-filled manner of reading the stories. Manto’s stories are divided into two sections: Partition and Sex and Sexuality whereas Chughtai’s stories are divided into three: Communal Colour, Sex and Sexuality, and The Zenana. The conflation of communality and partition, sex and sexuality in both the authors impart a pleasing quality of symmetry to the construction of chapters. This structural parallelism, again, also magnifies the thematic resemblances. Departing from the commonplace publication of individual collection of stories by each author (numerous editions of which are already available in the market) the decision to bring Manto and Chughtai together elevates this volume’s status. This gimmick makes the book more enigmatic and thereby, sellable in the market. Thus, the reception expected from the audience is very visibly made to work as a force driving the aesthetic binding of the book. The act of flipping encapsulates the materiality of the book and the commerciality of the venture is never concealed. However, contrary to expectations, the commercial exuberance affecting publishing is never allowed to compromise with the richness that the book offers. Almost all the famous pieces of both, including “Bu” and “Lihaaf” which have been warped up in several controversies ever since their first publication, are included as contents. The vast range of both Manto and Chughtai, their progressive essence and dense aftermath left by the black ink of their radical pens leap up from the pages cumulatively as a force that is hard to tame and reckon with.

Manto’s part of the book begins with “Toba Tek Singh.” This story has the singular power of conferring Manto’s genius to posterity. It charts out the portraits of various inmates of an asylum who are to be exchanged along the borders in the wake of the partition: Muslim madmen in Indian asylums will be sent to Pakistan and Hindu and Sikh lunatics in Pakistani madhouses will be handed over to Hindustan. In course of the narrative, the prospect of laying bare, the terms of this complicated political move to the already confused madmen becomes a serious ordeal. With scathing irony, Manto reveals how this transfer was the brainchild of a select few ‘wise’ men who single-handedly took decisions without the consent of the mute majority who lacked political power and thus, were helpless victims of the situation. It is as if the chaotic transfer of the madmen in the story, encompasses and emblematizes the arbitrariness in the entire event of the Partition that abruptly altered the life of millions who did not have a say to it. The story also engages in a detailed revelation of the dehumanisation of the madmen; like cattle they are paraded over barbed wires. Thus, it offers a classic example of the Foucauldian biopolitics where the bodies of madmen are strictly surveyed and managed by the State. The story also is laden with the mad speeches of the inmates that offer an interesting layer: appearing almost like King Lear’s bouts of madness or Lucky’s (from Beckett’s play) gibbering, it is as if the madmen are perceptive of what flouts the eye of sane people; their cryptic sentences have in them, an almost mystical wisdom such that their mad words expose bitter truths about the cruel, mad world. Manto exploits the trope of madness to hint at the sheer illogicality of communal sentiments that lead the madmen to form separate camps and abuse their opponents; the schizophrenic quality of the minor partition within the walls of the asylum metaphorically extends to the Partition that is being played out in a larger political stage. Again, Manto shows how all the inmates have been affected by the decision of transfer regardless of their religion, caste or creed. Even two Anglo-Indians suffer from anxiety regarding their future in the post-colonial nation. He exposes the magnanimity of the tragedy unfurled by the Partition and its overbearing effects on the lives of people. The way Manto has coloured the character of Toba Tek Singh is a testament to the excellent sensitive rendering of an equally sensitive subject: the warmth of the relationship between Bishan and his Muslim friend Fazl Din, their forced parting, the unfairness of the fact that Bishan had to leave Toba Tek Singh, the piece of land, which has been intricately intertwined with his existence behind, are imbued with deep pathos. Indeed, Toba Tek Singh becomes the icon standing on behalf of hundreds of people who having hurled across a dilemma were imprisoned in a no-man’s land between India and Pakistan; between memory and reality; between somewhere and somewhere: a dark abyss of nowhere. The second and third stories, namely, “Open It!” and “Frozen,” exalt the pathos of “Toba Tek Singh.” In both, we are brought face to face with the sheer violence that precipitated amidst the Partition and how women were more vulnerable to it. It is as if our anxious eyes follow the blank gaze of Sirajuddin in “Open It!” as he tries to find his daughter Sakina who had been running with him, trying to escape the plunder of the rioters who had forced their train to stop and stormed in. Hardly getting any time to process the graphic explicitness of his wife’s murder, he has to now grapple with the possibility of having lost his only daughter forever. The narrative tends to turn hopeful at a point when a group of young volunteers who wanted to rescue the victims of the train tragedy, promises to return Sakina to Sirajuddin. In fact, the narrator lets us know that the group members put their lives in harm’s way to rescue several women, men and children and bring them to safety. They finally discover a scared Sakina near Chuhrat and the readers along with the naïve Sirajuddin anticipate a happy reunion of the beautiful teenage daughter and her loving father. However, oddly, when the volunteers are again asked by Siraj as to the progress of their mission, they blatantly deny having found Sakina. The readers, at this, point are veritably puzzled and this puzzlement gives way to a climax that leaves them baffled. Horrified, Sirajuddin discovers the seemingly dead body of Sakina being rushed to the hospital. But it is soon understood that she is alive as she feebly opens the knot of her waistband to lower her shalwar for medical examination. The horror of the story becomes ringing as the father celebrates how his daughter is alive while the doctor breaks out in cold sweat as he stares at the mutilated, raped body of Sakina. Sakina, an underage girl of fifteen, will be alive yet dead. In “Frozen,” the start of the narrative engages with the bittersweet equations of the marital life of a couple. Eshar Singh tries to make love with Kalwant Kaur but their ritualistic conjugation is interrupted by tensions: Kalwant adeptly demands an answer about where Eshar had been roaming about for long and why is he acting so strange. Nothing that Eshar says to deviate her pointed questions works. Guessing that a woman might be behind Eshar’s untoward performance in bed, Kalwant charges at him and he nods feebly to confirm her suspicion. In a fit on anger and jealousy, Kalwant strikes Eshar with a kirpan. Bleeding profusely, Eshar tries to clear his name and confess his sins before death. He tells Kalwant that taking advantage of the partition riots, he looted a house and killed its inmates. Among them, was a girl who he had abducted to enjoy her body and while raping her, he realized that she was dead; a lifeless body of flesh. The death of the victim and her rapist gets conflated in an ice-like chilling ending.

The next section, Sex and Sexuality, gives a totally different flavour of Manto’s literary talents. While the earlier stories were grave and serious, the new stories are colourful and prismatic. “Smell” gives almost a poetic description of a cinematic rainy day. The narrative glows with the excitement of youth and the primeval joys experienced by a man as he wraps his naked body around the warm body of a woman. Randheer reminisces how one day, he beckoned a Ghatan to his house after he had noticed her getting drenched in the rain. Little did he know back then, that the encounter with this woman would be longingly remembered by him in the days to follow. Despite being an absolute stranger, Randheer did not take much time to realize an inherent connection with her: he felt deeply affectionate towards her and her innocent beauty aroused him like none other! Manto’s use of cliched images to describe the girl’s breast and the allure of her moist skin, might trigger reminders of blazon poetry where a woman’s body is subject to the violence of male gaze. However, although Manto’s story runs a risk of ticking all the conventions of narratives featuring “woman written by a man,” it is not entirely so. Manto in “Smell,” writes about unconventional beauty imparted by the girl’s odour that is nothing like the polished smell produced by deodorants; rather, it is enigmatic, nauseating yet strangely pleasant and addictive. Randheer’s attraction towards her is also as natural as the rain. Without sharing much of a conversation, he is drawn to her by a mystic, almost religious pull. The smell, Randheer finds increasingly difficult to explain. It is as here, Manto plays with the limits of language and magnifies its sensuality. The dark, uninviting underarms of the Ghatan is transformed into the seat of sweet purity like the earth sprinkled with water because of Randheer’s sexual/spiritual meditations. The smell haunts him as he lays beside his current wife and inflicts him with a sudden surge of bittersweet sadness and nostalgia: the most intimate he could ever feel was with a girl who is to be found no more… “The Black Shalwar,” is similarly about an odd relationship shared between Sultana, a prostitute, and Shankar whom she had chanced upon randomly one day. Manto never flinches while depicting the tabooed reality of a life led by a prostitute. In fact, he narrates the story in such a matter-of-fact way that the nitty-gritties of prostitution as a profession and its economic nuances are brought under sharp focus. And in doing so, Manto truly seems to be a radical and unconventional writer, a true modernist. As Sulatana ponders over her life while gazing at the rail, we are saddened by her loneliness and Manto allows her a humane moment by conferring to her the ability of thinking so soulfully. The character of Shankar is also bizarre. He is witty and sharp-tongued. He loves riddling Sultana. At a point in the story, he even tells her that their religious differences do not matter in the space where they have met (the red-light area). Thus, sexuality gets intertwined with politics and it is as if Manto indicates that they cannot be talked of in isolation. The story ends with the characteristic Mantoesque twist and leaves the readers wondering that if it were not for Manto, they would not have probably read about something like this. “Sharda” foregrounds a relationship that formed in between Nazir and the titular protagonist. Manto exposes routine exploitation faced by women in the profession as he shows how Karim, the pimp, allures clients for an underage, naive Shakuntala who has been forced almost to work in the hotel as a prostitute. Finding Shakuntala too frigid, Nazir is instead, aroused by the daunting personality of her elder sister Sharda and they form a connection that is more than a one-time transaction. Sharda falls in love with him and even comes over to stay while his wife leaves for Pakistan. However, Nazir, contrary to expectations, finds her constant presence nauseating and his feelings for Sharda change. The ending leaves a trace of sadness as we see how Sharda sensing this new development and her unwantedness, packs the baggage of her unrequited love for Nazir, leaves his house without leaving behind any information and keeps a pack of cigarettes behind for him as one final act of love, affection and devotion.

Chughtai, unlike Manto, commands a different type of interest: her concerns are pointedly gendered and women-centric. The cultural traffic and aesthetic registers of her stories predominantly obsess with the lives led by women. The first two stories under the section Communal Colour deal with the social complexities forged by inter-faith romantic relationships. “Kafir,” begins with the playful communal insults hurled between Pushkar, a Kashmiri pandit, and Munni, a Muslim girl. Both of them argue for the superiority of their own faith and abuse the other’s. Chughtai shows how the air of communal hatred could not even spare the daily conversation shared between two childhood friends. However, the equation between Munni and Pushkar is never let to get too heated and serious. In fact, Munni poses as a Hindu to participate in Diwali. It reveals that for the two, religion and faith despite retaining a spiritual magnificence could be twisted into playful performances whenever the situation commanded. Growing up, the word ‘kafir’ that they had often called each other to debate on who is the graver sinner, acquires a new meaning as they realize the love they have for each other: indeed, such a marriage will be scorned upon as sinful by normative society. However, risking the consequences, they elope to give their love a chance. The story ends with their usual sweet banters and loving arguments which capture the unchanged dynamic between the two even as they embark on a brave new journey in life. Pushkar and Munni become the Kafirs of the romances from the Kafirs in the eye of religion. In “Sacred Duty,” too Samina to the horror of her parents marries a Hindu guy, Tushar. In the course of the narrative, both the in-laws try to exploit their marriage and reduce it to the needs of publicized religious gimmicks. First, Tushar’s parents get Samina converted and then, Samina’s parents trick Tushar to get converted into a Muslim as well in the pretence of finally accepting the terms of their marriage and to extract revenge. The story ends with the couple leaving behind a letter addressed to both sets of parents pinpointing the disgusting importance they gave to their egos and religion than to their children’s happiness. Through the character of Samina’s father, Chughtai also ridicules the liberals who otherwise conceal clouds of prejudices in their souls.

In Sex and Sexuality, there are three stories. “Lihaaf” contributed to Chughtai’s rise to literary fame. The story charts out the same-sex relationship between Begum Jaan and her servant Rabbu as witnessed from the perspective of a child, the begum’s niece. The story informs varied complex issues. While sexual pleasure is usually associated with the West and a Third World subject is perceived as a barbaric, by foregrounding a Muslim Indian woman as an agent of erotic play, Chughtai addressed something that could not be fathomed in her times. Creating a moment of sexual tension between the child and the begum, Chughtai also enters a more tabooed terrain of child sexuality. She flouts the conventional flower-like innocence of the girl as she shows her being dangerously close to sexual knowledge. Again, she points out how while the Begum’s husband can profess his pederastic interests in public spaces and in broad daylight, the Begum and Rabbu have to confine their acts of sexuality to the private homosocial space of the women’s inner quarters. However, while definitely queer, one cannot appropriate the story as an instance of lesbian activism as it has certain ambivalences: the Begum gets interested in women as an alternative only when she realizes that her marital life will not come to fruition and the child is horrified by the shaking of the quilt, rendering the sexual act to almost an unnameable monstrosity. Thus, this unnameable sexuality suggests two things: it makes a suggestion towards the queer politics of visibility (women’s status in such a politics because of their gender) and how solely because of the invisibility they could carry on their sexual acts unnoticed in an enclosed space removed from the public gaze. “The Net” shows two girls engaged in sensuous bath time reverie, a temporary escape from their otherwise entrapped and suffocating lives, and the nuanced sexual tension mediating the complications of their relationship. “The Mole” traces the unrequited passion felt by a painter Choudhury for Rani, a model he had recruited from among the slums which ultimately leads to the demise of his artistic excellence.

In the last section, The Zenana, Chughtai evokes the stifling atmosphere of conjugal home that terrorizes Islam women. “The Wedding Suit,” shows how Kubra’s mother slaves and wastes away to appease the glutton and ungrateful Rahat. It ends with a tragedy as Rahat, exhausting the spirits and wealth of the family, leaves for his home to get married to someone else. “Gainda,” shows how a young widow consummates relationship with her friend’s, the narrator’s, elder brother and gives birth to a child for which she is abused and hated by the rest of the family. It also delineates the desire engendered in the narrator who is envious of Gainda’s ability to gratify her sexual desire. The last story, “Touch-Me-Not,” portrays the darker side of motherhood as an institution that is almost never talked of in an Indian culture committed to glorify it. Thus, the three stories are filled with the exuberant details of the ordinary lives led by women that were not exactly thought of as fit subjects for writing. But Chughtai brilliantly harnesses poetry in the mundane and fuses personal with the political as she emphatically zooms in on the hardships faced by women.

Thus, the collection shows that both Manto and Chughtai are essentially ‘social’ authors. Both of them held idiosyncratic positions in the literary scenes and as members of a religious minority group, were always already in a deferred state. However, the divorce from cannon, enabled them to talk undauntedly about things like sexuality. Channeling the grassroots energy in sexuality and showing subalterns getting engaged in sexual acts, they try to hint at how sexuality can also be political and it is never secondary. Rejecting the safety of romantic exuberance, they highlighted the jarring reality of the streets and the hardships of the lowlife. Their language is also clear-cut and pedestrian. Their narratives cannot afford any laziness and have the urgency of wanting to participate in serious political discourses. Often misinterpreted as foul imitators of Western vulgarity, Manto and Chughtai refused to get appropriated by the mainstream surge of a Bhadra Lok, upper-class and Hindu cultural discipline.

Often collections of stories tend to be mistaken as a unified body capable of standing in place of the authors. The writerly selves tend to become extensions of their public personas. To clear such a tendency, Chughtai’s biographical piece on Manto, “My Friend, My Enemy!” is also included in the collection. We can see the similarities as well as differences between the persons of both the authors and their literary characters. The chapter also highlights the dynamics of Manto and Chughtai’s relationship as literary contemporaries and close friends. It trails their acquaintance to their gradual estrangement. This piece, thus, by highlighting the agreements and disagreements between Manto and Chughtai offers an interesting dialectical energy to the collection’s structure.

Lastly, Manto and Chughtai: The Essential Stories, proves Michael Gamer’s observation as to how collections can be “powerful representative forms.” It unites the efforts of two literary comrades as they try to unmask the face of a society that is already naked; it stands as a hymn written by them to the lightness that struggles to emerge from the dark and to the complexities of all human relationships.

Also, read a book review of Unbound written by Sanjukta Dasgupta, reviewed by S. Vincent and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments