Translated from the Italian by Brenda Porster

Image used for representation.

Finally it‘s dark, and, thank goodness, the armchair next to her is empty. No one can see her, no one knows her, no one knows she’s here. She can relax, finally.

Her mobile is off.

In a minute, the film will start: someone else’s story, maybe about an imaginary person, in any case no one she knows. She is only a spectator. If the film is well-done, she’ll be able to lose herself in it, to live someone else’s life for two hours or so.

Has she turned off the mobile? Better check. But where is it? She thought she’d brought it.

She’s always loved cinema. There was a time when she enjoyed so-called experimental films, even the nouvelle vague, which follows along of the lines of the nouveau roman. Now they annoy her. All those citations, self-citations, frames within frames, etc., keep her from what she’s come to do.

All that constantly reminding the public they are in front of a screen, not watching the unfolding of real life but of an illusion. Nowadays those films seem to have been produced under glass, made for people to observe with deference or detachment, or simply to glance at briefly before moving on to think about something else.

She also avoids science fiction, like almost all films with fantastic themes. It’s so rare that they manage to create a parallel world—future, present or past—perfect enough to make you forget the real present. Almost always there is some exaggeration, some far-fetched stereotype that reminds her that she‘s sitting in an uncomfortable seat because she’s paid for a ticket.

Then there are the remakes—at times shrill, at others carelessly done—and the thought of the original brings her back to the real world.

What just fell down? It must be the mobile. It must have slipped out of her coat pocket. She was about to check whether she’d turned it off. No, it was only an empty tin can that her foot had banged; so the mobile must be in the car… On the other hand, films on the martial arts are fine; they have no pretensions of being meta-cinematographic works of art, and the absolute control of bodies in movement seems to be a complementary face of the mind in movement, of a still, meditative life, the proof of possible harmony. To be sure, there is usually a decidedly commercial side, but if she wants she can manage to ignore that, she only needs to watch with the same innocence and sense of enchantment she had when she read adventure stories as a child.

The commercials are over, it’s dark once again, the screen is dark, too. The film is about to begin.

Oh lord, the mobile. It’s ringing. She knew it. But where is it? Right pocket, left pocket, of her jacket. Inner pocket, outer pocket, of her bag. It’s not easy to find things. Her bag is very large. She carries too many things around with her. A book for idle moments. Another, smaller book in case the first one isn’t right for her mood, a folder with bills to be paid, paper tissues, make-up, glasses. Where could it be? But no, the man in the row in front of her is switching off his. Heads turn. No doubt they are launching accusing looks in the dark. What a relief. It’s not hers. She already has a hard time putting up with the home phone. It makes her jump, almost out of fright, every time it rings. The volume is always too loud and if she turns it down the tone is disturbing, almost threatening. And—if after taking a deep breath she picks up the receiver—phone company offers, fake prizes, announcements that the landlady is coming to check on things, the bank…

The mobile was even worse. She’d refused to have one as long as she could. At work, they tried to convince her to get one, her children had one. Her husband, too. All the talk of emergencies, the children out in the street at night, not being able to reach their mother. The talk of how much easier it is to organize your life. The time you save when you can make a call walking along the street! In the end, she received one as a Christmas gift, and since then she has tried to live with it. If before she would sometimes wake up because of a nightmare, now she wakes up because she hears the mobile ringing. If she were to check, she would find it —apart from some rare exceptions. In any case, it was always silent. There had been no calls in the night.

She’s not totally relaxed when the film starts. But she really needs those two hours in a safe place, in the dark, with sounds coming only from the loudspeakers. She tries to concentrate, to empty her mind, to banish from the theatre everything irrelevant to the story she is about to see.

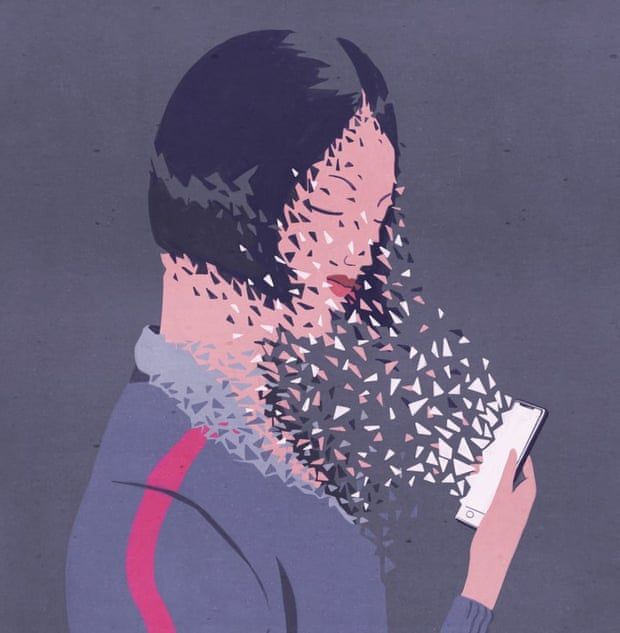

No, it’s not possible. Help. It’s ringing again. More softly, weak, as though something is muffling it. But she didn’t think she’d brought it. It’s becoming an obsession. She puts her hands back into her pockets. In the bag. Nothing. It’s getting louder, more insistent. It’s hers, and it is ringing over her. She can feel the vibrations. There it is, it’s ringing under her jersey. But there’s nothing else here. Only skin. Herself. Her flesh. But it’s ringing. A terrifying thought. From inside. Don’t be delirious. Look for it! Concentrate, take it easy. She thinks people are starting to turn around. She is sweating. There, it’s stopped now. It’s not possible. She waits, paralyzed. At once, it starts up again. It’s there. Inside her. On the right, under the solar plexus. She has to take it out. Immediately, without losing a minute. Take it out and turn it off. Make it stop. But how, what with? She has a pencil case with some pens and a pair of scissors in her bag. Scissors for paper, no, they’re no good. But at the bottom, under the folder with the bills, there is still a plastic bag from the stationer’s. Her son had asked her for some things for his technical drawing class—pencils with both hard and soft leads, a soft rubber, a small sharp knife. That’s it, the knife! It’s just what she needs. She has to make that phone be quiet once and for all. In the dark, she grabs the lower hem of her jumper and of her blouse under the elastic of her bra to free the skin around her belly-button. Not to panic, she tells herself, keep steady, concentrate!

For an instant, she stops breathing, then, determined, she carefully places the point of the knife on her skin.

Also, read bilingual translation of short French poems by Eric Sarner, translated by Hélène Cardona, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments