BOOK REVIEW BY SANCHAYITA BISWAS

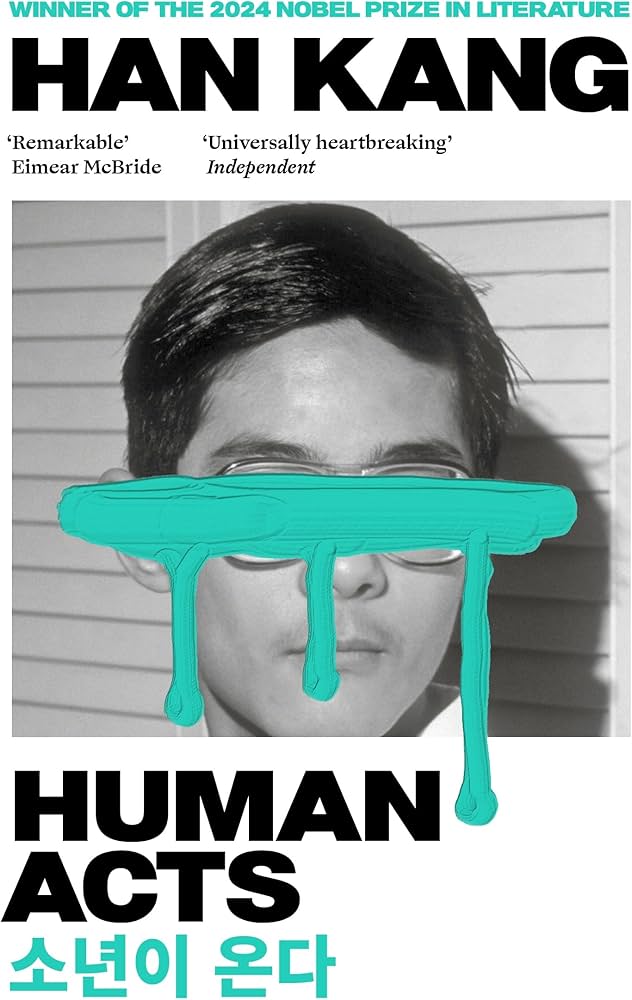

“The state represents violence in a concentrated and organized form. The individual has a soul, but as the state is a soulless machine, it can never be weaned from violence to which it owes its very existence.” This famous quotation of Mahatma Gandhi reverberated in my mind after I turned the last page of Han Kang’s Human Acts (2014). Han Kang is an extraordinarily powerful South Korean author. Her prose is experimental and largely metaphorical. She addresses violence, grief, suffering, trauma in a distinct poetic style. Originally written in Korean, Human Acts was published in serialized form in the literary blog Jangmun in 2013-2014. In 2016, this novel was translated into English by Deborah Smith.

Human Acts documents the socio-political catalysts of the Gwangju uprising. In 1979, the assassination of South Korean president Park Chung Hee resulted in civil unrest and imposition of martial law. People’s demand for greater democratisation and withdrawing the martial law were crushed by organised violence on unarmed students led by the Government on 18th May, 1980. When the whole Gwangju descended on streets to protest, a ten-day long unopposed massacre was organised by the Government. Human Acts portrays a distorted collage of this time.

This polyphonic novel deals with the personal experience of six characters. They physically revolve between 1980 and 2013. But psychologically, all of them are stuck in those days of 1980’s Uprising. There is Dong-ho, the teenage boy who comes to a gymnasium where dead bodies of the civilians are kept for identification and cremation. Dong-ho comes to find his missing friend’s corpse, but gets entangled in the voluntary work of handing over bodies to their families. There is the missing friend’s soul who witnesses the army’s soulless inhumanity while waiting by his own putrid corpse, unable to leave it behind. There is the book editor whose survival guilt suffocates her for years. Then comes the political prisoner who is caged in the memory of inhuman torture of his prison days. The fourth voice is of a factory girl who carries her trauma of sexual torture for twenty-two years. The sixth chapter voices the monologue of Dong-ho’s mother whose guilt of outliving her son and outrage towards the state fills us with profound sadness. The epilogue is the author’s homage to the victims of the uprising.

The novel is written predominantly in the second-person narrative. There is an unnamed ‘You’ who could be a dead-alive person, a living-dead person, the reader, a victim or a survivor. A sense of dislocation, anonymity creates a realisation that “you” is applicable to any civilian of any dictatorial state at any point of time. Kang creates a binary by addressing the state as ‘they’. Human Acts deals with the theme of identity crisis and nationhood. The trust of being a countryman gets shattered when the state declares war on its civilians. When the military kills civilians instead of protecting them ,the concept of nationhood collapses.

The relationship between body and soul is a sacred metaphor to Kang. To her, the violation of the body annihilates the intactness of the soul. Noticing the grotesqueness of unclaimed bodies at the gymnasium, Dong-ho wanders, “How long do souls linger by their bodies?” He contemplates, “When a living person looks at a dead person, mightn’t the person’s soul also be there by its body’s side,looking down at its own face?” As if to answer this question, Dong-ho’s friend lingers near his decomposed body. The women of the Labour union, who possess no slogan or weapon, expose their bodies as a mode of resistance. The naive factory girl recounts : “Everyone held the naked bodies of virginal girls to be something precious, almost sacred, and so the factory girls believed that the men would never violate their privacy by laying hands on them now, young girls standing there in their bras and pants. But the men dragged them down to the dirt floor. Gravel scraped bare flesh, drawing blood.” Kang tries to decipher where exactly our humanity resides in our animal forms.

The title of the novel in the source language is Soneonyi Onda which can roughly be translated as ‘A boy comes’. At the centre of all the voices, the presence of Dong-ho works as a metaphor of the shattered innocence of an individual soul and planned brutality of the state. The English title, however, embodies different connotations. It creates a dissonance where innocence and violence coexist as human behaviour. Here State uses bayonets, cudgels, inventive torture methods, sexual brutality to reinforce ‘peace’. Dictatorship considers it a ‘human act’ for the greater good. Deborah Smith, in her introduction to the translation, notes that Human Acts is ‘a reminder of the human acts of which we are all capable, the brutal and the tender, the base and the sublime.’

Han Kang’s use of language is very poetic, very personal. That poetic sublimity is exquisitely present in Deborah Smith’s translation. The constantly changing timeline, regionalism and historical background never fades a bit in the translation. Human Acts is not a comfortable read. It evokes the most essential question Han Kang posits, ‘What is humanity? What do we have to do to keep humanity as one thing and not another?’

Also, read The Bride Chooses by Omkar Gupta, translated from Bengali by Manjira Majumdar, and published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments